Are Democracies Doomed to Fail?

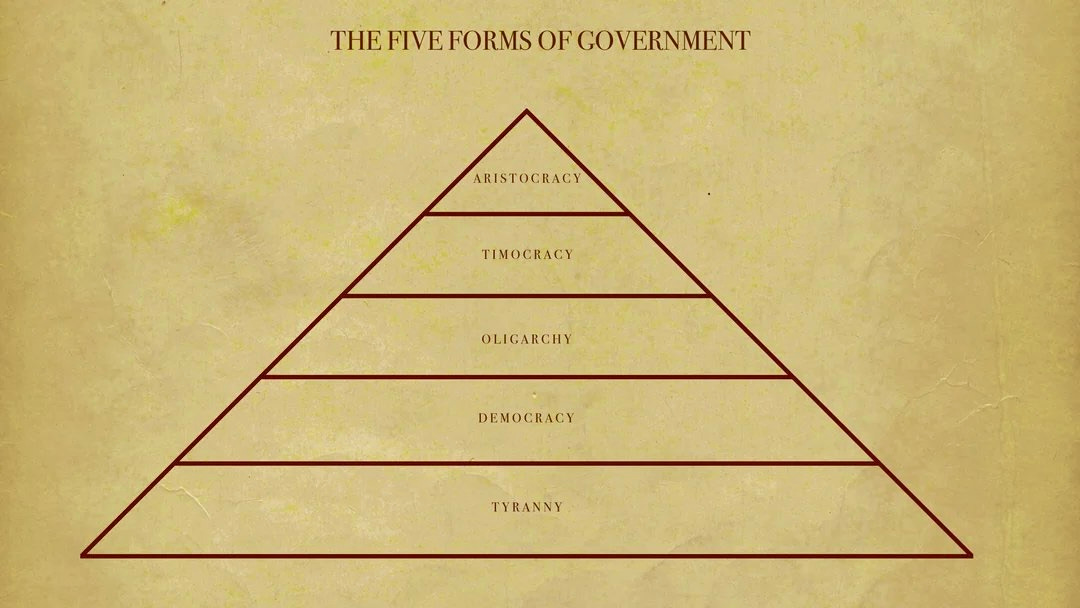

Plato’s 5 stages of government

Few would argue that there are many texts as foundational to the West as Plato’s most famous dialogue, The Republic. And yet, The Republic stands opposed to almost everything we think of as the basis of a free and fair system of living today: democracy, liberty, free expression.

These things, as Plato saw them, are not only corrupting to the souls of man, but, when used as the basis of an entire political system, destined to unleash the cruellest tyranny upon the people that uphold them.

Plato sorts political systems into five types: aristocracy, timocracy, oligarchy, democracy, and tyranny. These regimes can be observed in isolation, but they are also posited as a linear progression, wherein each form is predetermined to devolve into the next — aristocratic society is destined to become timocratic, which is destined to become oligarchic, and so on.

But this is only a surface-level reading, because the dialogue is less a political commentary and more a study of the human soul. Plato’s “city in speech” is a study of man himself, and the city embodies man’s soul writ large.

This article unpacks each of Plato’s five systems, and the forces of politics and human nature that drive all democracies (and all other forms of government) into ruinous mob rule.

And crucially, we’ll examine the question: at what stage do we find ourselves today?

Reminder: this is a teaser of our members-only deep dives.

To support our mission and get our premium content every week, upgrade for a few dollars per month. You’ll get:

Full-length, deep-dive articles every weekend

The entire archive of great literature, art, and philosophy breakdowns

Members-only podcasts and exclusive interviews

The State & the Soul

Plato didn’t write his dialogue in the abstract. His life unfolded during the most turbulent years of Athens, a city ravaged by political upheaval, plagues, and war. He experienced multiple forms of Athenian governance, and even saw his eccentric tutor Socrates executed by way of democratic process.

No surprise, then, that his five forms of government rank democracy only one above tyranny:

However, his Republic was not simply an attempt to construct the perfect government. Plato was trying to tackle a deeper question: is it beneficial to be just? Isn’t injustice often more beneficial for the man who acts selfishly?

Plato explores this through the character of Socrates and various interlocutors who pose questions to him. Socrates’ core argument is that injustice always consumes itself — just as injustice slowly tears apart the soul, so too the unjust city is destined to fall to ruin.

In this sense, the five forms of government reflect the five stages of the human soul, which The Republic describes as having three distinct parts: rational, spirited, and appetitive. The rational part is that which seeks truth and keeps the other two in check, and as we’ll see, each regime differs in how it ranks the three.

We’ll start with timocracy and leave aristocracy to the end, since that is Socrates’ (and Plato’s) solution to the chaos that will now unfold…

1. Timocracy – Rule by Honor

Timocracy is government by those who prize honor above all else. Plato models his example on Sparta, a disciplined martial state where rulers are driven by ambition and citizens admire courage more than they do wisdom.

The timocratic man is ruled by his spirit, the part of the soul that craves victory and recognition. He looks up at those of military status, but down upon the producers and serfs — timocratic man is obedient to his rulers, but harsh with his slaves.

This produces order and vigor in society, but not justice, because while the spirit is noble, it is also unstable. And over time, the hunger for esteem mutates into hunger for possessions — why?

Imagine a boy who grows up witnessing his father chase honor in the military, but then he is betrayed by the system somehow or treated with injustice. Learning from this, the boy knows in order to protect himself he must accumulate something other than honor — wealth. And crucially, wealth appeals because it still provides the recognition that his spirit craves.

2. Oligarchy – Rule by Wealth

Oligarchy is rule by the wealthy. Political power belongs to those with property, and the poor are excluded from influence.

The oligarchic man’s soul is no longer led by the spirit, but by his appetite, though he manages to restrain it. Socrates calls him “stingy and a toiler, satisfying only the necessary desires and not providing for other expenditures, but enslaving the other desires as vanities…”

His thrift and self-restraint might sound reassuring, but there’s a catch. His appetite is restrained not by virtue, but by fear of losing what he has: “because he trembles for his whole substance.” Yes, his better desires control his worse ones (for now), but this is no basis for lasting stability.

Because he’s not grounded by virtue, the oligarchic man becomes a predatory lender to the next generation:

“Unwilling to control those among the youth who become licentious by a law forbidding them to spend and waste what belongs to them — in order that by buying and making loans on the property of such men they can become richer and more honored.”

–The Republic, 8.555c, Allan Bloom translation

The children of oligarchs, themselves “luxurious and without taste for work of body or of soul,” are ill-equipped to compete, and the rich grow richer as the poor swell in numbers. In a society ruled by the wealthy few, it’s probably obvious how things are going to unravel. The two groups aren’t really living in the same city:

“Such a city's not being one but of necessity two, the city of the poor and the city of the rich, dwelling together in the same place, ever plotting against each other.”

–The Republic, 8.551d, Bloom

The wealthy guard their privileges, while the poor grow resentful. At a deeper level, the state is brittle because wealth alone is never enough to secure unity. A city held together by money rather than virtue cannot last, and when the poor finally overthrow the rich, oligarchy slips into the next form: democracy…

3. Democracy – Rule by Many

At first, democracy feels like liberation:

“And isn't the city full of freedom and free speech? And isn't there license in it to do whatever one wants?”

“That is what is said, certainly," he said.

"And where there's license, it's plain that each man would organize his life in it privately just as it pleases him."

"Yes, it is plain."

–The Republic, 8.557b, Bloom

The principle good in this system is freedom, and equality a close second. The city itself provides an equal voice to everyone, and any and all lifestyles are tolerated. The democratic man himself is generous, “attached to the law of equality,” but unmoored:

“Often he engages in politics and, jumping up, says and does whatever chances come to him; and if he ever admires any soldiers, he turns in that direction; and if it’s money-makers, in that one. And there is neither order nor necessity in his life, but calling this life sweet, free, and blessed he follows it throughout.”

–The Republic, 8.561d, Bloom

Notice an issue here that isn’t present in the other systems: no single, ordering principle dominates. Equality itself is the hierarchy. Wealth as an ordering principle certainly wasn’t perfect, but freedom is an even lesser system to guide your life. The democratic man’s soul is ruled by reason, spirit, and appetite, each taking turns to lead.

Democracy unchains the appetite of the oligarchic man, but the unchained appetite fails to distinguish precisely what it should want — pleasures belonging to both bad and good desires are accepted here. It is freedom in every sense except for that which is most important: freedom from one’s own desires.

With the old wealth and honor hierarchies now dissolved, the danger is that all distinctions will soon dissolve. Socrates describes how parents no longer rule their children, foreigners are on equal standing with citizens, and even the animals walk about town as though they were free.

So, what happens when all desires are equal and nothing exists to direct them? The ground is fertile for change, and one single appetite will now come to dominate and enslave all others:

"tyranny is probably established out of no other regime than democracy, I suppose — the greatest and most savage slavery out of the extreme of freedom."

–The Republic, 8.564a, Bloom

However, it begins not with the sword, but with the rise of a gracious and gentle champion. Here’s how democracy unravels, and how Plato proposed to fix it…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Culturist to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.