Are You Smarter Than a Coal Miner?

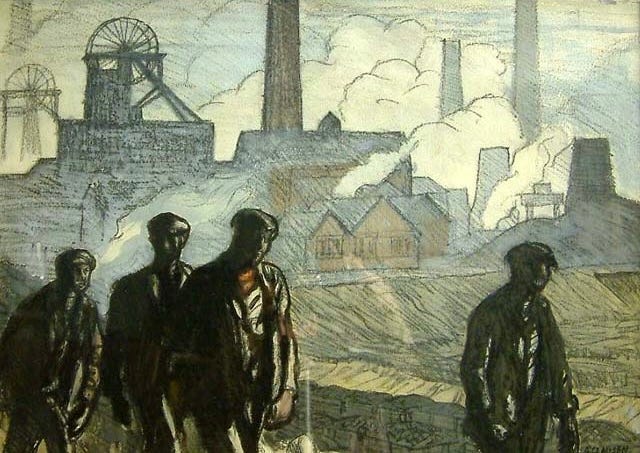

The intellectual life of working-class Victorians

The intellectual life was never something that only the elites enjoyed.

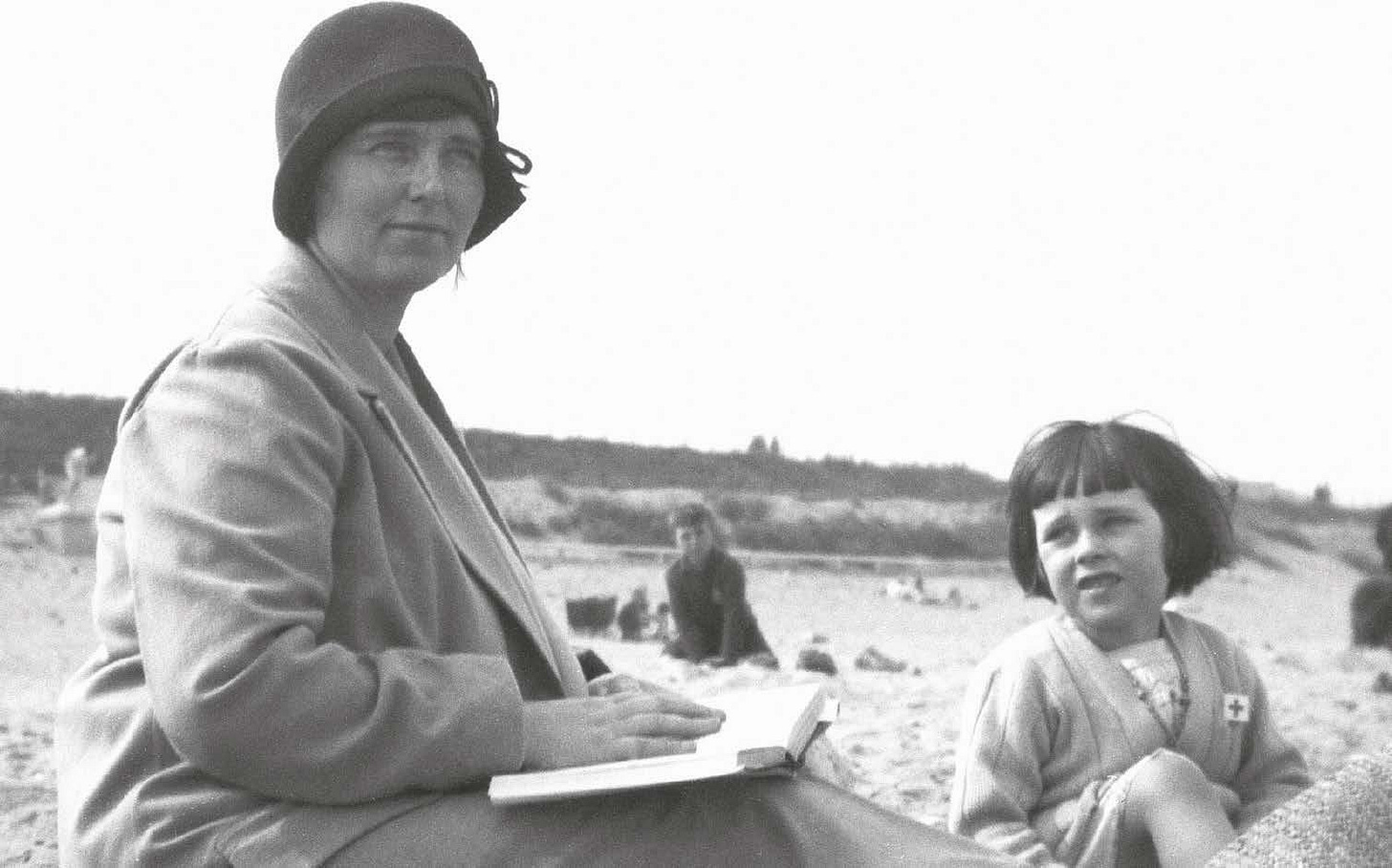

In 2001, university professor Jonathan Rose published The Intellectual Life of the British Working Classes, one of the most illuminating cultural histories of the past few decades.

Through an extraordinary range of sources including autobiographies, letters, library archives, miners’ reading circles (more on those later), and Sunday school curricula, Rose overturns the assumption that the working classes of industrial Britain were largely uneducated or intellectually disengaged.

Indeed, his book proves quite the opposite — that their reading habits and interior lives were often far more cultivated than those of the average person today.

In this article, we explore seven of the most surprising revelations from The Intellectual Life of the British Working Classes, and look at how our own culture compares to that of the Victorians…

Reminder: you can support us and get tons of members-only content for just a few dollars per month:

Full-length articles 2x per week

The entire archive of premium articles and podcasts

We are about to start reading Dostoevsky’s “Notes from Underground” in our subscriber book club — the first meeting is TODAY, October 22nd, at noon ET. Join us!

1) A Hidden Culture of Learning

Rose begins by methodically laying out the proof that there existed a massive, self-directed culture of education among working-class people. He shows that they read voraciously, with many even choosing to self-study Latin or history after long shifts underground or in factories.

Coal miners, mill workers, and mechanics built their own libraries and formed reading societies to study Shakespeare, Dickens, Milton, and even Plato. It was a grassroots intellectual movement that grew independent of elite institutions, a “democratization of learning” on a massive scale.

2) High Culture Was Never Elitist

One of Rose’s key points is that canonical literature — what is now often labeled “high culture” — was not the preserve of the upper classes. Rather, it was the working classes who took the canon most seriously.

While elites might have consumed culture for status, ordinary readers engaged with it morally and personally, seeing in Shakespeare and the classics a means of moral development and self-mastery. This revelation directly challenges the 20th-century academic assumption (inspired by postmodernism and Marxist cultural studies) that “high culture” is inherently exclusionary.

3) Reading as Self-Improvement

As previously mentioned, working-class readers saw literature as a tool for self-improvement. But while education would certainly improve their prospects for social mobility, it is often the aspects of moral improvement that people of the time valued most.

Pulling from autobiographies and letters, Rose shows that workers often described reading as a form of inner liberation, citing writers like Ruskin, Carlyle, and Dickens as their moral guides. They read with a degree of seriousness we rarely see today, treating their books as beloved companions in a lifelong pursuit of wisdom.

4) A Decline in Cultural Aspiration

The Intellectual Life of the British Working Classes also traces what Rose sees as the tragic decline of this culture of self-directed education. Specifically, he shows how the rise of mass media and television use following WWII made a preference for reading slowly give way to one for passive entertainment.

Without romanticizing the past, Rose argues that earlier generations’ intellectual independence, and specifically their willingness to grapple with difficult texts, puts modern culture to shame. He suggests that the democratization of education paradoxically coincided with a lowering of intellectual standards — just like how more people than ever attend university today, yet popular culture as a whole is much less intellectually vibrant than it was 50 years ago.

5) Autobiography as Evidence

Much of Rose’s argument rests on hundreds of working-class autobiographies. These personal writings reveal that workers were deeply reflective about what they read, and acutely aware of how it shaped their worldview.

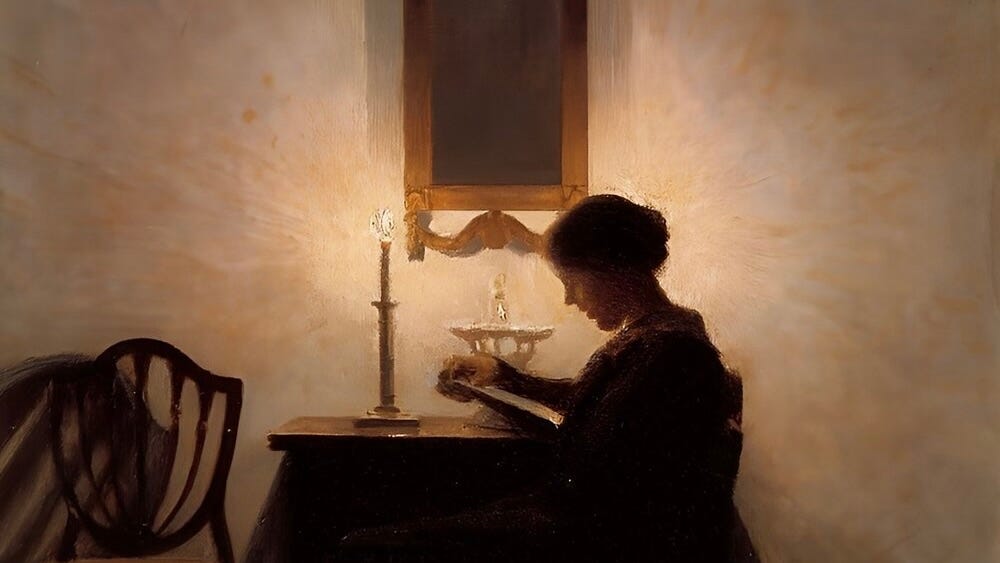

In their writings, these men and women often recorded how specific authors — everyone from Shakespeare to Marx — changed the course of their lives. One miner recalls reading Paradise Lost underground by candlelight, and another describes saving for months to buy a volume of Carlyle. Their testimonies give Rose’s book a profoundly human dimension, showing that the working classes were just as emotionally invested in their pursuits as they were so intellectually.

6) Intellectual Independence & Dissent

Rose goes to highlight how reading fostered independent thought and shaped political beliefs. Many of these autodidact workers were drawn to socialism, Chartism, and other reform movements, but their intellectual foundations were markedly eclectic.

Reading Marx beside the Bible or Ruskin beside Darwin, they debated politics with a nuance and seriousness that can only be born from real engagement with the texts. They combined Enlightenment rationalism, Christian ethics, and classical literature in unique ways to question authority, yet never lost sight of the moral values required to restrain fanaticism.

This intellectual independence, Rose argues, distinguished them from both the aristocratic establishment and later ideologically driven academics.

7) Reclaiming the Canon for Everyone

Ultimately, Rose’s thesis is that the great works of Western civilization belong to no single intellectual class, but that they are the people’s inheritance. Indeed, the working-class intellectual tradition treated them as such long before universities began to question their relevance.

The example provided by the workers of industrial Britain exposes the smallness of our own modern excuses, such as claims to have “no time” to read, or our addiction to entertainment. On this point, however, The Intellectual Life of the British Working Classes provides much needed encouragement — it demonstrates that people living in objectively worse conditions than our own still managed to cultivate a beautiful interior life through reading.

And if they could do so in their circumstances, then certainly we can do the same in ours.

There’s a simple blueprint here for us. Make your table a small scriptorium. Choose one demanding book, set a modest pace, read aloud, copy a paragraph by hand, memorize a few lines and carry them with you through the day. Treat it as stewardship, not a sprint. If the miners once did this after twelve hours underground, we can manage it after dinner. In my own little corner at Reclaiming the Biblical Worldview, that’s the goal: To learn to read again in a way that restores our sense that the world is speaking. That things carry meaning.

The absence of television and cheap passive entertainment in the 19th C. may be a part of this. Another part is that many people who would have gotten a high school and university education had they been born in the 20th Century did not do so in the 19th C due to accidents of birth or circumstances. As a lifelong learner and reader, I understand these people. Your brain is still hungry even if it is not force-fed.