Can American Democracy Survive?

Tocqueville's "Democracy in America"

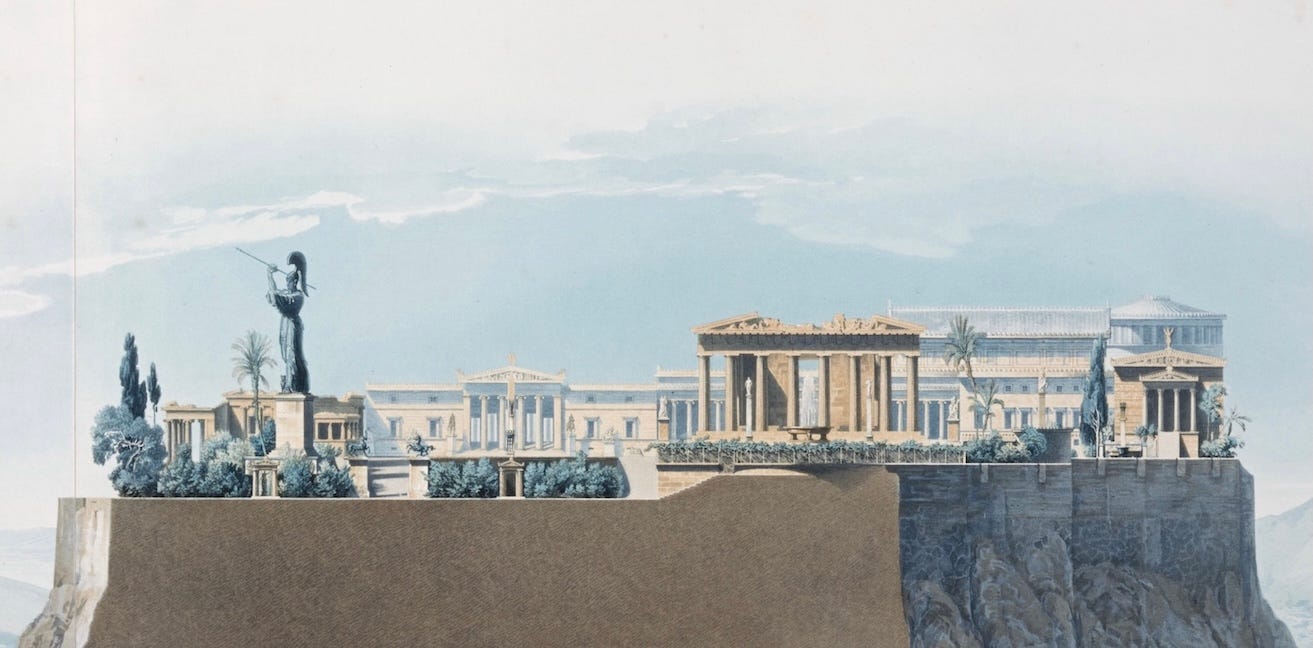

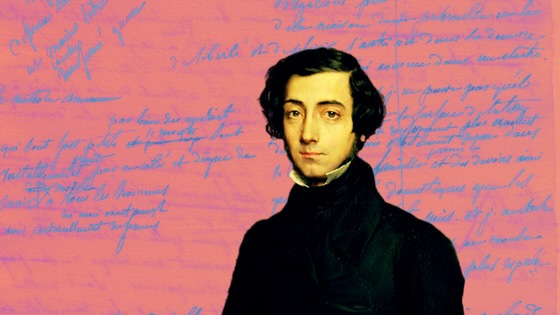

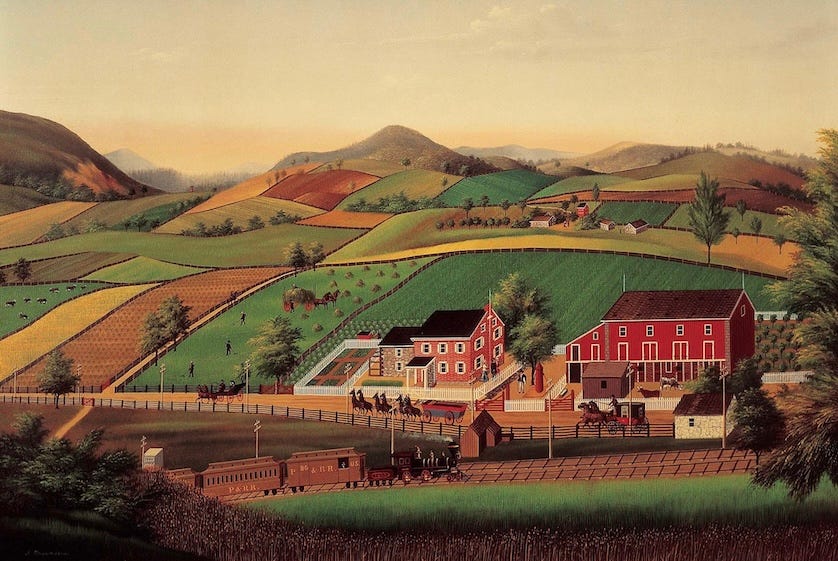

In 1831, French aristocrat Alexis de Tocqueville traveled to America to study the state of the fledgling nation. As an admirer of democracy, he was eager to see how the American experiment was working for its citizens, and how the national consciousness of the United States had evolved in the decades following the Revolutionary War.

What Tocqueville witnessed both amazed and terrified him.

On the one hand, he saw and appreciated the unique strengths that made the “American experiment” truly exceptional. But on the other hand, he perceived the cracks in the foundation of the new nation, and predicted how they would bring about its end.

Upon his return to France, Tocqueville published his observations in a two-volume work entitled Democracy in America. To read it today is to read the closest thing to political prophecy: many believe Tocqueville’s evaluation of America has aged like fine wine, and that the vast majority of his observations are just as true today as they were when he first penned them nearly 200 years ago.

Today, we look at three core themes addressed by Tocqueville in his work, and explore to what extent they still apply to the America of 2026…

This newsletter is free, but if you’d like to support us, please consider a paid subscription — we are a reader-supported publication. You’ll get:

Full-length articles 2x per week

The entire archive of content (180+ articles, essays, and podcasts)

Our book club has just started reading Plato’s Republic. The first meeting is on Wednesday, January 14, at noon ET. Join us!

1. Liberty vs. Equality

Tocqueville lived through one of the most turbulent eras of French politics: in the 53 years of his life, France had three monarchies, two empires, and one republic. Yet amidst these constantly-shifting political sands, Tocqueville found an ideal to help root himself, writing:

I have a passionate love for liberty, law, and respect for rights. I am neither of the revolutionary party nor of the conservative…Liberty is my foremost passion.

Yet when he traveled to the United States, he witnessed that American ideals of equality threatened to infringe on ideals of liberty. In Tocqueville’s understanding of government, a healthy democracy should be able to give both of these ideals their due. But in America, he observed:

…one also finds in the human heart a depraved taste for equality, which impels the weak to want to bring the strong down to their level, and which reduces men to preferring equality in servitude to inequality in freedom.

In Tocqueville’s experience of America, the idea of equality was often used, whether intentionally or not, to erode the foundations of true freedom…

2. Individualism

One of the things Tocqueville most admired about the United States was the degree to which regular Americans joined together to work towards common goals, often becoming politically active in the process. This kind of individualism, he observed, empowered local communities and minimized reliance on a distant federal government.

Yet at the same time, Tocqueville also diagnosed the downsides of individualism, describing it as a:

…calm and considered feeling which disposes each citizen to isolate himself from the mass of his fellows and to withdraw into the circle of family and friends…With this little society formed to his taste, he gladly leaves the greater society to look for itself.

Tocqueville recognized that the American penchant for individualism, while at times helpful in building up communities, could just as easily tear them down by isolating their members and rendering them indifferent to the concerns and tastes of others.

3. Tyranny

Despite his obvious affection for democracy, one of Tocqueville’s biggest concerns was that Americans would take the concept too far. He feared American democracy could easily descend into what he deemed a “tyranny of the majority”. On this point, he wrote extensively:

In my opinion, the main evil of the present democratic institutions of the United States does not arise, as is often asserted in Europe, from their weakness, but from their irresistible strength. I am not so much alarmed at the excessive liberty which reigns in that country as at the inadequate securities which one finds there against tyranny.

An individual or a party is wronged in the United States, to whom can he apply for redress? If to public opinion, public opinion constitutes the majority; if to the legislature, it represents the majority and implicitly obeys it; if to the executive power, it is appointed by the majority and serves as a passive tool in its hands. The public force consists of the majority under arms; the jury is the majority invested with the right of hearing judicial cases; and in certain states even the judges are elected by the majority. However iniquitous or absurd the measure of which you complain, you must submit to it as well as you can….

Although Tocqueville believed in the power of the people to dictate their political future, he also realized that this could go too far in an unhealthy direction. Even the “vox populi,” he wrote, was not immune from criticism:

A majority taken collectively is only an individual, whose opinions, and frequently whose interests, are opposed to those of another individual, who is styled a minority. If it be admitted that a man possessing absolute power may misuse that power by wronging his adversaries, why should not a majority be liable to the same reproach?

So what was Tocqueville’s solution to this dilemma? Fortunately for us, it’s no mystery, as Tocqueville spells out his thoughts exactly:

If, on the other hand, a legislative power could be so constituted as to represent the majority without necessarily being the slave of its passions, an executive so as to retain a proper share of authority, and a judiciary so as to remain independent of the other two powers, a government would be formed which would still be democratic while incurring scarcely any risk of tyranny.

I do not say that there is a frequent use of tyranny in America at the present day; but I maintain that there is no sure barrier against it, and that the causes which mitigate the government there are to be found in the circumstances and the manners of the country more than in its laws.

Perhaps most interestingly, Tocqueville claims that the “manners” of American society more than its laws are what held tyranny at bay in the early days of the American experiment. But was he right in his prognosis?

And if so, then to what extent do these same “manners” still hold back the forces of tyranny today?

Thank you for reading! If you’d like to support our work, please consider taking out a paid subscription — we are a reader-supported publication. Premium readers get:

Full-length articles 2x per week

The entire archive of content (180+ articles, essays, and podcasts)

Striking how Tocqueville isn’t really talking about democracy at all. Not in the way we usually do today anyway. He’s looking past the scaffolding. Past all constitutions and checks and balances. As if he already knows they’re secondary.

I'm no expert on Tocqueville but from this article he seems to imply that freedom doesn’t start with rights. It starts with people who know how to stop themselves. Who accept that not everything bends to them. That kind of thing isn’t written anywhere.

And once equality turns sour once it stops meaning shared worth and starts meaning flattening difference something slips. Quietly but surely. The paperwork gets done. Everything looks fine from the outside. But it’s thinner. More fragile. That's a scary place to live.

The danger is slow drift. Character dissolving without anyone really noticing. Is that why he talks about manners? They go first. So maybe asking whether democracy survives is the wrong scale. Too big and too clean a question. The real question is smaller and more messy:

Do we still live in ways that train us for freedom at all?

By manners he means culture. Compared to the early 19th century the US culture, as in Europe, has changed. The West, in general, went from a more aristocratic privilege-obligation-honor-divine order culture to a sacred victim, entitled parasite culture.