Can Beauty Really Save the World?

What Dostoevsky meant

If your social media feeds are anything like mine, you see this phrase at regular intervals, lifted from Dostoevsky’s The Idiot:

“Beauty will save the world.”

The line has been quoted so often that it now floats free of its original weight. It appears in posts set against sunsets, church ceilings, or the ecstatic art of Michelangelo. Few, however, recognize the depths of Dostoevsky’s claim.

The problem is, it’s a statement that sounds poetic but also feels vague and naïve. It’s an appealing idea, but lacking as something of real use to us.

How, exactly? How will beauty save the world? Why should anyone hang their hopes on a claim so vague?

Precisely what Dostoevsky meant has been subsequently wrestled with by thinkers from Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn to Pope Benedict XVI. Let’s examine Dostoevsky’s claim, and how to apply it in our own lives…

This is a teaser of our paid subscriber essays. If you’d like to support our work, please consider subscribing — this is a reader-supported publication. You’ll get:

New, full-length articles 2x per week

The entire archive of content (180+ articles, essays, and podcasts)

We are reading Plato’s Republic in our book club for January. The next discussion is on Wednesday, January 28, at noon ET…

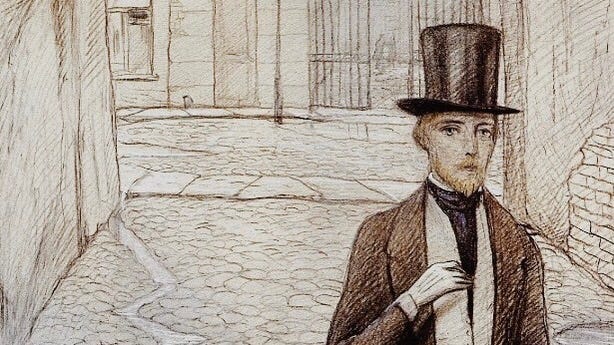

A Positively Beautiful Man

As mentioned, the phrase comes from the novel The Idiot, spoken indirectly by the character Prince Myshkin. The 26-year-old prince is an “idiot” because he’s a naïve optimist, a positively good man in a Russian society corroded by cynicism and nihilism. The people around Myshkin reject him for his innocent nature and foolish generosity, though at times, they find him too piteous to attack.

The prince is also a committed Christian, and this is a source of tension. Myshkin is seen as a “holy fool,” unequipped with the kind of cynical rationalism necessary to navigate the broken society he’s plunged into. He sees the good in everyone, and fails to see that his goodwill toward others won’t be reciprocated. Worse, he’s blind to the destructive psychological forces at work in those around him.

When we encounter the quote in question, it’s attributed to Myshkin but spoken in mockery by the intellectually sharp but nihilistic Ippolit:

“Is it true, prince, that you once declared that ‘beauty would save the world’? Great Heaven! The prince says that beauty saves the world! And I declare that he only has such playful ideas because he’s in love! Gentlemen, the prince is in love. I guessed it the moment he came in. Don’t blush, prince; you make me sorry for you. What beauty saves the world?”

Myshkin is mocked and rejected by modern Russians precisely because of his affection for “outdated” notions like beauty and romance. Yet he clings to them. When Myshkin later discovers a horrific murder that he is unable to process, his psychological fragility (and epilepsy) overwhelms him — he is destroyed because his goodness is incompatible with the world he inhabits.

The Insufficiency of Reason

Despite Myshkin’s lack of success in Russian high society, even the hardened characters of The Idiot feel themselves drawn to his good nature, although their ruthless rationalism and self-interest tell them otherwise. Myshkin is a living alternative to their own inner emptiness.

This is an example of something that Dostoevsky returns to repeatedly across his novels: human beings are not primarily motivated by reasoned argument. We can argue ourselves into (or out of) almost anything, yet this can never formulate a sense of meaning.

Similarly, in The Brothers Karamazov, we encounter another young “holy fool” in Alyosha, who cannot compare to the intellect of his older brother Ivan, a sharp rationalist. Ivan is superior in debate, and when he lays out his case against a just God (especially his argument from innocent suffering), Alyosha cannot win. He does not have a counterargument that closes the logical gap in his faith exposed by Ivan.

And yet, readers of The Brothers Karamazov do not fall in love with Ivan (though they often see themselves in him). They are drawn to Alyosha and the kind of life that is lived out by his philosophy. He doesn’t have all the logical answers, but he lives oriented toward something that transcends the need for logical arguments in the first place.

Be careful not to interpret this as anti-intellectualism — Dostoevsky was making an important point about the outer limits of argument. He knew well that reason can expose the fractures in one’s beliefs, but it cannot supply what comes next.

So, where does beauty come in?

Beauty, like the characters of Alyosha and Myshkin, is living proof of a kind of truth that exists beyond the reach of logic. Beauty is something that you cannot be reasoned into or out of, and it simply grabs you.

But that doesn’t mean that living in tune with beauty is easy. As we read in The Brothers Karamazov, “beauty is not only fearful but also mysterious.” Dostoevsky’s “beauty will save the world” claim is not some comforting platitude, but a profound challenge — to live as a “positively beautiful man” in the modern world is difficult.

Fortunately, though, Dostoevsky’s masterpieces reveal how we can start to live up to what beauty demands of us…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Culturist to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.