Does History Repeat Itself?

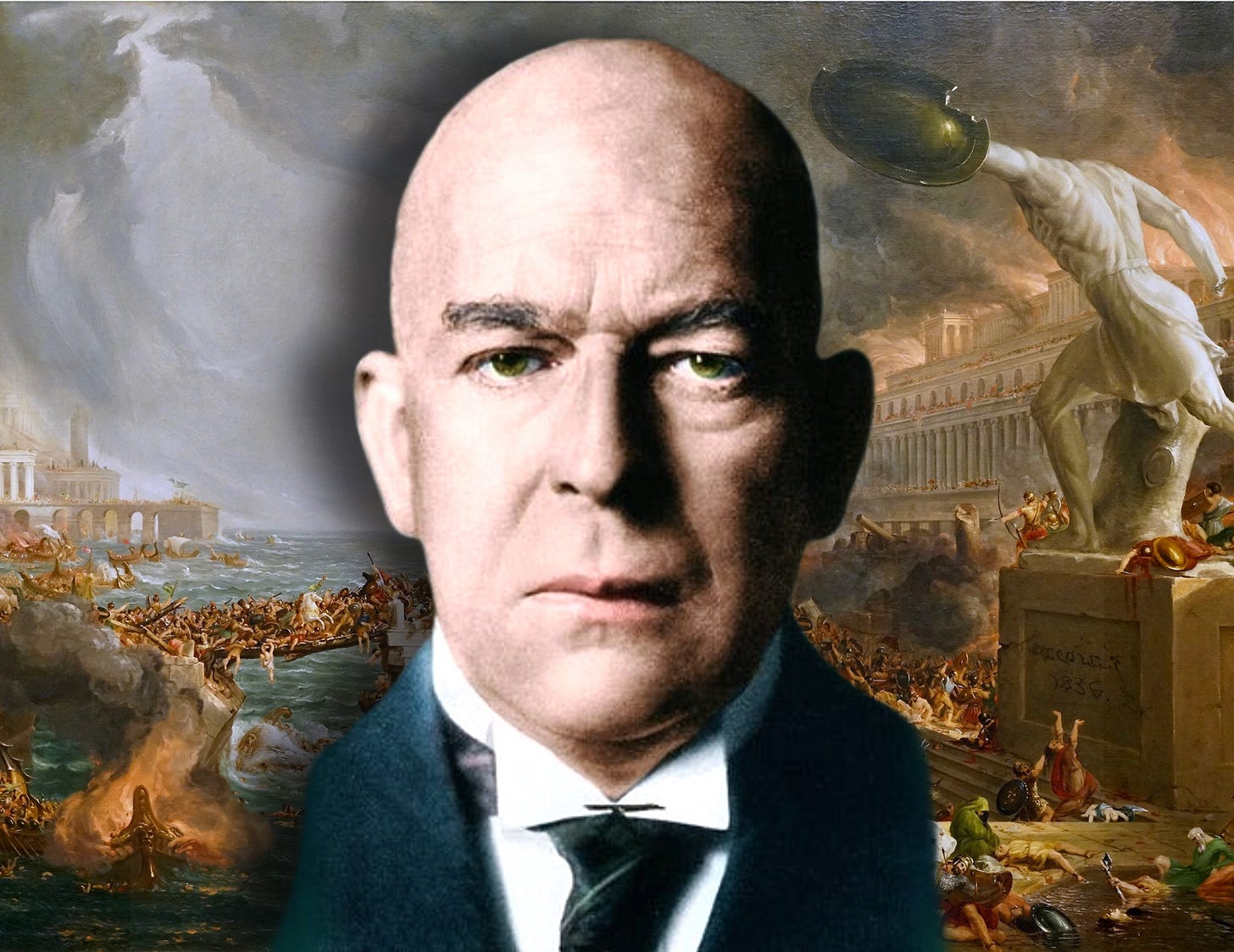

The Caesar of the 21st century...

Our culture is uneasy with the idea of decline. It teaches us instead to see history as a steady ascent from ignorance to knowledge, from poverty to abundance, and from tyranny to freedom.

It’s a comforting story — but what if it's wrong?

In 1918, a German historian named Oswald Spengler published The Decline of the West, a sweeping, ambitious theory of history. In it, he rejected the Enlightenment notion of never-ending linear “progress”. Civilizations, Spengler argued, are not constantly marching toward utopia. They are instead living organisms that grow, age, and die.

Spengler believed that Western culture — which he called the "Faustian" civilization — was already in its twilight. The signs were there for anyone who dared to look: declining faith, exhausted art, shallow materialism, and bloated cities. A century later, his ideas feel eerily prescient.

Today, we explore Spengler’s work The Decline of the West to see what it reveals about the world we live in today — and what it predicts about the chaos and upheavals you will live through in the first half of the 21st century…

The Life Cycle of Civilization

At the heart of Spengler’s work is a rejection of Enlightenment universalism. He insisted that there is no single human history, only the histories of distinct cultures. Each high culture — Babylonian, Egyptian, Chinese, Classical, and so on — is a unique entity with its own soul, its own form, and its own rhythm of life.

Spengler described the life cycle of these civilizations in seasonal terms. “Spring” is the first major cultural awakening: a time of myth, religious fervor, and spiritual discovery. It is when a people first sense their destiny, and is an age of foundational faith and symbolic expression. “Summer” then brings the full flowering of creative power as architecture, science, and philosophy emerge in a mature form, driven by a deep confidence in the culture’s mission.

But in “autumn,” the culture begins to turn inward and become more self-reflective. Artistic innovation slows as forms are perfected and knowledge becomes increasingly abstract. By “winter”, the culture has calcified. What remains is not culture but mere “civilization” — technical brilliance without inner fire, administration and bureaucracy without vision or vitality.

In a nod to the famous legend in which a scholar trades his soul for knowledge and power, Spengler deemed Western culture "Faustian". For him, this name captured the soul of the West as a civilization defined by its endless striving for the infinite.

Whereas Classical man sought proportion and harmony, Faustian man seeks to transcend all limits, to pierce beyond the visible and the known. This impulse shaped everything in the West — from the soaring verticality of Gothic cathedrals to the discovery of the New World, and the boundless curiosity of modern science.

But the same impulse that drives Western culture is also what exhausts it. Spengler argued that by the 19th century, the West had begun to enter its civilizational winter. Its innovative spirit, creative fire, and zeal for life all started to dim.

What remained was the proliferation of something disastrous — what Spenger deemed “world cities”...

The Age of World Cities

Winter, in Spengler’s view, is dominated by these so-called "world cities”. These aren’t just large urban settlements, but swollen centers of commerce, spectacle, and abstraction. Most critically, they are cut off from the land and the culture that gave them birth.

In Spengler’s day, cities like Berlin and New York were pushing toward 5 million people. But he predicted that these world cities — alongside many others — would rapidly grow in size to 10 to 20 million inhabitants (a 2018 UN estimate puts the larger metropolitan area of New York City at roughly 18 million). Cities of this size, Spengler argued, would grow incomprehensible in scale and increasingly detached from human needs.

But what’s worse, the world city hollows out important elements of culture. Art loses its soul. Religion becomes private therapy. Politics becomes theater. The population of a world city becomes atomized, concerned only with comfort and consumption. Family life erodes, birth rates fall, and the spiritual unity that once defined a culture rapidly dissolves.

The Faustian impulse, once heroic and metaphysical, is now commercial and self-referential. The striving for transcendence becomes a hunger for novelty. In fact, Spengler believed the West would spend its final energy perfecting economic, legal, and technological systems, but without asking why they even mattered.

So what happens when a civilization starts to collapse under its own weight? According to Spengler, history was clear on this — that culture can expect nothing less than the fall of democracy and the rise of caesarism.

And for Western culture, he predicted it would all take place in the early 21st century — when a new Caesar shall rise…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Culturist to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.