Does Might Make Right?

The uncomfortable truth about power

We’d all like to think we live in a just world. A world in which the strong take care of the weak, and where good ultimately triumphs.

But if we’re being honest, we know that’s not the case. There is no shortage of injustice in the world or examples of rulers abusing their power. For many people, this is a painful realization they come to only in adulthood.

But to the Greeks, it was common knowledge.

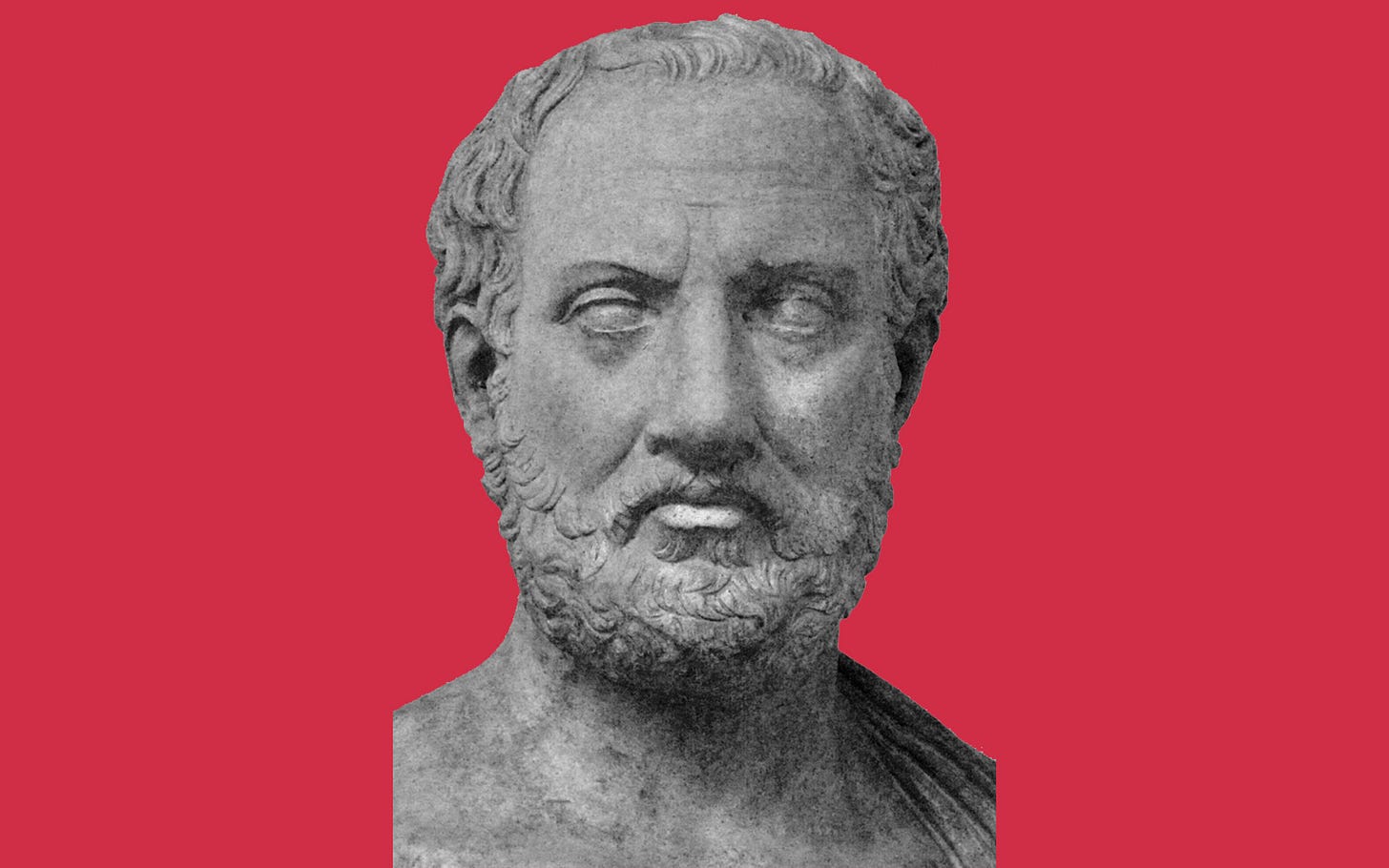

Writing nearly 2,500 years ago, the Greek historian Thucydides highlighted this in a famous passage from his History of the Peloponnesian War. Known today as the “Melian Dialogue”, the section reveals the harsh reality of power politics. It has inspired leaders and politicians ever since, and debates continue to rage as to what the proper response should be to the reality Thucydides portrays.

Today, we look at the Melian Dialogue to respond to the question, “does might make right?” The answer, you might be surprised to learn, is far from straightforward…

Reminder: we are a reader-supported publication. This newsletter is free, but if you’re able to support us, please consider a premium subscription. You’ll get:

Full-length articles 2x per week

The entire archive of content (180+ articles, essays, and podcasts)

Our book club is currently reading C.S. Lewis’s Screwtape Letters. The second discussion is on Wednesday, February 25, at noon ET. Join us!

The Dialogue in Context

In 431 B.C., war broke out between Athens and Sparta. Athens, the naval power of the Aegean, quickly set about bringing a multitude of Greek islands under its sphere of influence. In 416 B.C., an Athenian delegation finally arrived at the island of Melos.

They gave the Melians a simple ultimatum: surrender and pay tribute, or be destroyed. The islanders’ response, and the corresponding back-and-forth with the Athenians, is what is now termed the “Melian Dialogue”.

In it, the Melians make several appeals to the Athenians. They cite the fact their island is neutral, and that it would be unjust for the Athenians to conquer them. They also say that the power of Athens won’t last forever, and that one day Athens might be punished for its unjust actions.

The Athenians, for their part, respond that Melos’s neutrality doesn’t matter. If they let Melos off the hook, then other islands would feel free to rebel too. But crucially, they point out an obvious fact: Melos is in absolutely no position to negotiate with Athens. The Melians have zero hard power, and they won’t get any help from their allies. The Athenians are in fact making a kind offer to Melos, seeing just how little negotiating power the island has.

Yet the Melians continue to appeal to the idea of justice, and that’s when the Athenians put it bluntly, in one of the most famous lines from history: “the strong do what they can, and the weak suffer what they must.”

So what do the Melians finally decide?

Duty, or Delusion?

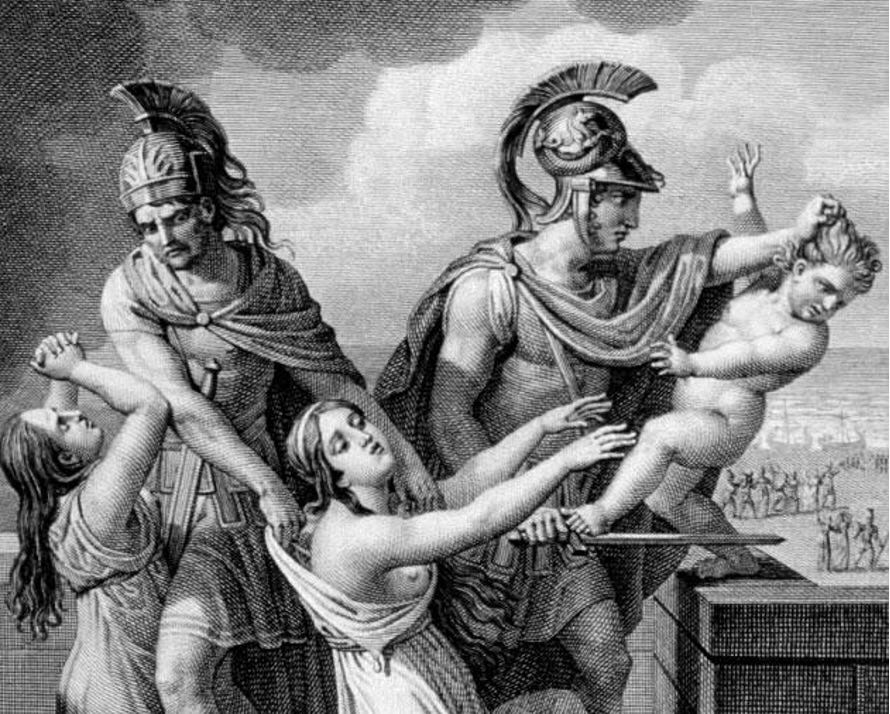

The Melians reply that for the sake of honor and justice, they will choose to defend their homeland. True to their word, the Athenians then conquer the island, executing all military-age men and selling the women and children into slavery. 500 Athenians then settle on the island, completing the erasure of Melos.

Just like that, a 700 year old civilization is wiped off the map.

This is where responses to the Melian Dialogue begin to vary wildly: some point to the malice and injustice of the Athenians, while others blame the Melians for refusing to come to grips with reality. Is it better to fight to death for a noble cause, or to spare your subjects suffering by not being delusional?

Are the Athenians wrong in saying that “the strong do what they can, and the weak suffer what they must” ? Do strength and power necessarily entail selfishness and tyranny?

Fortunately, we don’t have to answer these questions ourselves. We can simply look to the example of the Romans, who formulated a brilliant response to the dilemma of Melian Dialogue…

The Uncomfortable Truth

In considering the reality of the Athenians at Melos, the Romans came to an interesting conclusion. Instead of moralizing or taking sides, they simply made the observation that although might does not make right, it does make what is.

In other words, they recognized that power alone does not give you the moral authority over others. But at the same time, they knew that moral authority alone can’t defeat hard power. So to reconcile these two, they coined the famous phrase se vis pacem, para bellum: “if you want peace, prepare for war.”

In just five words, the Romans managed to reconcile the often conflicting realities of power and morality. Not all the powerful simply “do what they can” while the weak “suffer what they must”. It is indeed possible for a superior power to be benevolent to its inferiors — but at the same time, not all of them are. For this reason, those who desire to hold the moral high ground must be prepared to defend it by strength of arms.

War is never desirable, but this does not make pacifism a virtue. Rather, peace must be guaranteed by strength: it is soldiers who create the environment in which poets can flourish. Those who seek to defend the cause of justice, therefore, would do well to learn from the mistake of the Melians. If you want peace, prepare for war, as it is only through strength that the weak are protected.

Indeed. Whichever moral systems can assert their principles through power are the ones that will predominate in the world. A moral system that cannot (or will not) do this will be eradicated, regardless of the content of its particular beliefs. Moral clarity without power is posturing, and power without moral clarity is tyranny. Both principles and power are required.

Wow. I so want to believe this isn't true. But we live in times when the truth of the consequences of unchecked power make it a compelling argument.