Dostoevsky's Warning About Wisdom

And why you need imagination

What makes a man smart? What makes him wise? And what are the distinctions between intellect and wisdom?

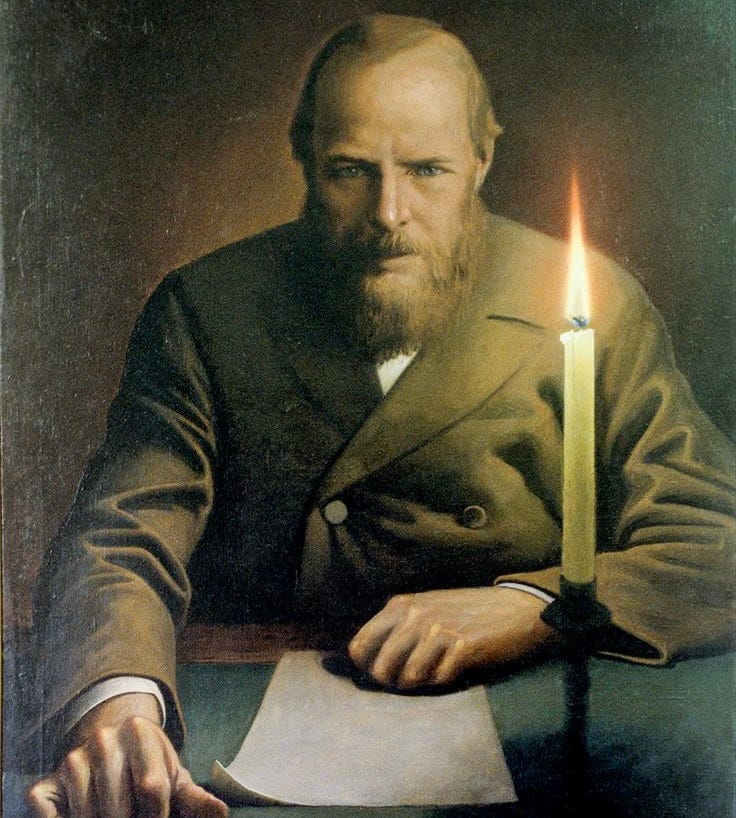

These are questions at the heart of the debate over what constitutes a great mind. Throughout history, various philosophers, authors, and artists have shared their thoughts on the matter — yet few did so as compellingly as Fyodor Dostoevsky.

Today, we examine Dostoevsky’s life and writing to see what the Russian author believed about the nature of a great mind. We’ll also explore his surprising idea about what wisdom really is, and why his advice is so important in our increasingly unstable modern world…

Reminder: this is a teaser of our members-only deep dives.

To support our mission and get exclusive content every single week, upgrade for a few dollars per month. You’ll get:

Full-length articles 2x per week

The entire archive of premium articles and podcasts

Membership to our bi-weekly book club (+ subscriber chat room)!

Our paid subscriber Great Books Club is currently reading Dostoevsky’s “Notes from Underground”. The next meeting is on Wednesday October 22, at noon ET — join us!

Revolution in the Soul, Not the Streets

Dostoevsky was born in 1821 at the Mariinsky Hospital for the Poor in Moscow, where his father worked as a doctor. From the very beginning of his story, he lived between two worlds — the educated class his father aspired to, and the destitute masses his father served.

These circumstances provided Dostoevsky with something few Russian writers possessed: first hand experiences with every layer of society. He studied literature and philosophy alongside Moscow’s educated elites, while simultaneously absorbing the folk tales and humble faith of the peasants at the hospital. The result was that the young Dostoevsky acquired an instinctive understanding of both common life and the intellectual elite, and a rare ability to see both worlds as they truly were.

Yet despite this grounding in real human experience, Dostoevsky still got drawn into the idealism of his age. In his twenties he joined the Petrashevsky Circle, a small group of political idealists who met to debate utopian socialism. But when the group was arrested 1849, Dostoevsky’s idealism quickly came crashing down.

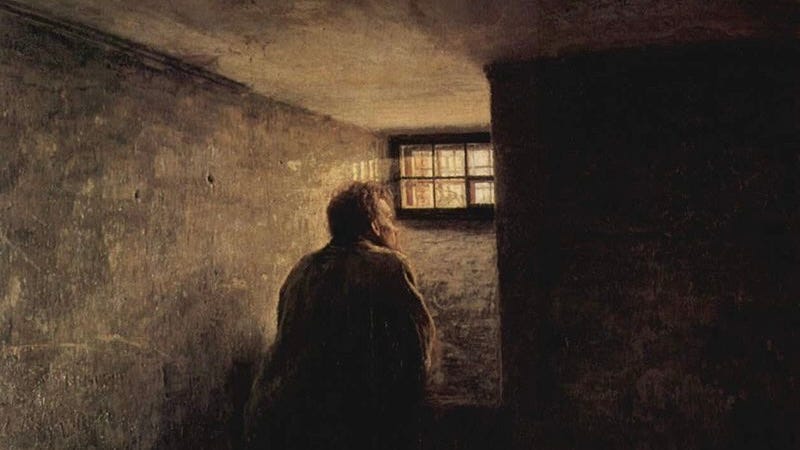

Sentenced to four years of hard labor in a Siberian prison camp, Dostoevsky was stripped of books, comforts, and ideology. Yet because of this, he was able to come face to face with the depths of the human soul, and finally unlock the key to intellectually reconciling the two worlds of his youth.

The solution? It would start not with a revolution in the streets, but in the soul…

What Wisdom Isn’t

For Dostoevsky, the greatest danger to the intellect was mistaking knowledge for understanding. He saw how easily intelligence, when divorced from conscience, could turn destructive.

The character Raskolnikov from Crime and Punishment is a clear example of this. He is the epitome of a man who grasps an idea intellectually, but never absorbs it morally. He convinces himself that superior men have the right to commit crimes for the sake of humanity — yet the moment he acts on this belief, he collapses under its weight. His faculties of reasoning, for however well developed they might be, are worthless when they result in the suffering of both himself and others.

Dostoevsky understood that an intellect untested by empathy and unanchored in real-world experience breeds both arrogance and despair. It creates people who believe they think deeply, when in reality they have only skimmed the surface of truth.

He explores this idea further in Notes from Underground, where the Underground Man presents himself as a defiant individualist — even though his rebellion is entirely secondhand. He has simply borrowed the ideas of the radical intelligentsia and turned them inward, mistaking imitation for independence. While it’s easy to believe his misery stems from an excess of thought, it in fact stems from his failure to think for himself.

Dostoevsky likened pieces of knowledge to dabs of paint: by themselves they are useless, and the entirety of their value depends on how you use them. If you mix tastefully with other colors, you create a masterpiece; but if you mix them poorly, even the most vibrant colors on the canvas get muddied and ruined.

So what then is the secret to utilizing knowledge wisely?

To this question, Dostoevsky offers two answers, and shows why imagination is absolutely crucial on your journey to attaining wisdom. The key to it all is best expressed in Crime and Punishment, by Raskolnikov’s friend Razumikhin:

“It is better to go wrong in one’s own way than to go right in someone else’s”…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Culturist to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.