Dresden's Architectural Miracle

And the rebirth of culture...

Architecture is never neutral. Whether it’s designed to invite or intimidate, it is always sending a message. Sometimes it can be used to inspire a populace — other times, it can be used to demoralize and humiliate them.

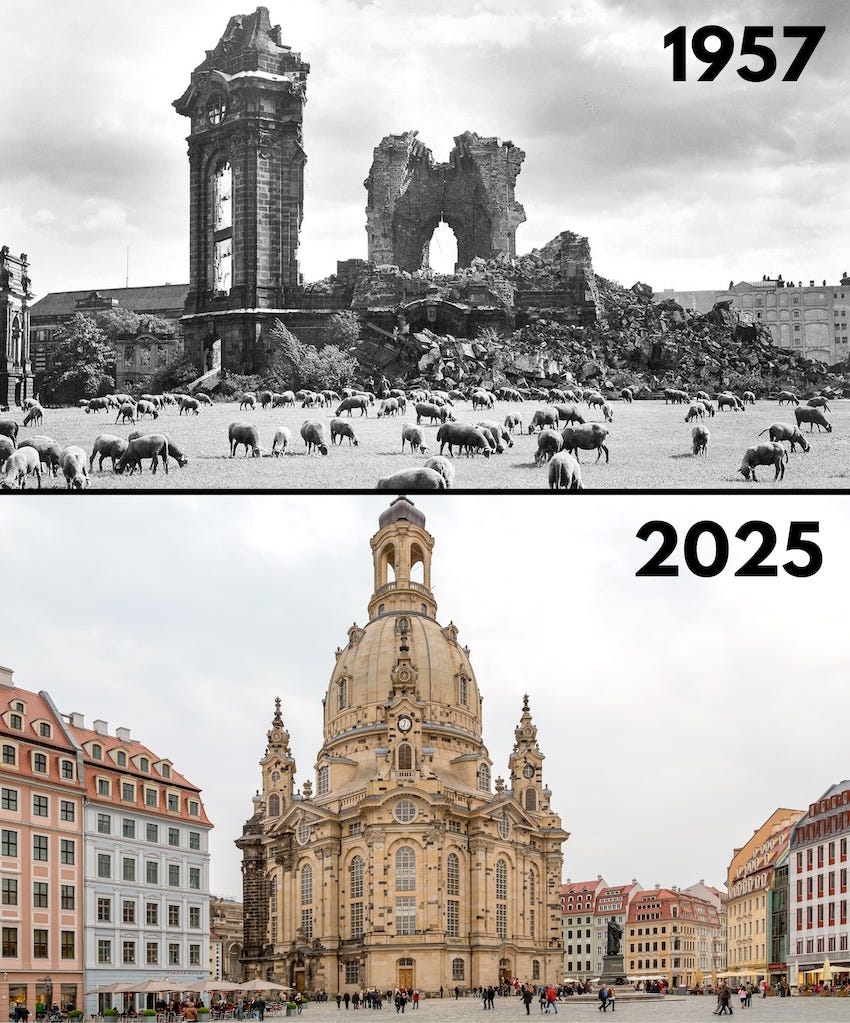

Few buildings serve as a better example of this than Dresden’s greatest church, the Frauenkirche. Once the jewel of the great German city, the Frauenkirche was firebombed by the Allies in WWII and then left in ruins by Soviet occupiers.

It stayed that way until the last decade of the twentieth century, when resilient locals finally rebuilt it. In the end, it is a truly inspirational story — but like most heartwarming tales, it is one that begins in ignominy…

Reminder: you can support our mission and get tons of members-only content for a few dollars per month:

Full-length articles every Wednesday and Saturday

Members-only podcasts and exclusive interviews

The entire archive of great literature, art, and philosophy breakdowns

The Fall of an Empire

Germany suffered a humiliating defeat in the First World War. The peace terms outlined in the Treaty of Versailles required it to pay insurmountable debts which left its citizens impoverished, starving, and demoralized.

As Germans faced a future of hopelessness, one opportunistic and charismatic leader offered a way forward: Hitler’s message of German pride rallied the country, driving Germans to fight to the bitter end of WWII — and the end was bitter indeed.

The Allied powers sought to hasten the end of the war by deploying a tactic of “strategic bombing.” It was a plan that, under its technical title, meant destabilizing Germany by focusing on non-military targets: factories, hospitals, and even civilian homes. The Commander in Chief of the British Air Force at the time, Arthur Harris, described it as such:

The ultimate aim of an attack on a town area is to break the morale of the population which occupies it. To ensure this, we must achieve two things: first, we must make the town physically uninhabitable and, secondly, we must make the people conscious of constant personal danger.

It’s no surprise this campaign of demoralization took aim at the buildings most dear to the German people. In 1945, one of the most infamous raids occurred, the firebombing of Dresden. Apart from the 25,000 civilians killed, 90% of the city center was destroyed — including the once-glorious 18th-century church, the Frauenkirche.

Seeing their luminous church reduced to rubble certainly lowered the spirits of Dresden’s citizens. They must have wondered: is the promise of a glorious future worth sacrificing the beauty of the past?

A Nation Divided

Germany offered her unconditional surrender later that year. Eager to avoid the mistakes of the First World War, the Allies sought to help Germany transition to a new, post-Nazi state — without wholly crushing the country once again.

The four Allies (France, England, the United States, and the Soviet Union) divided Germany into sections, each stepping up to administer one quadrant. The system was tenuous at best. As the political situation born from the aftermath of WWII evolved into a Cold War, the four-way administration disintegrated.

The three western quadrants fused to form West Germany, while the USSR set up a puppet government to rule the East. No longer a mere administrational entity, the Soviets now occupied Germany…

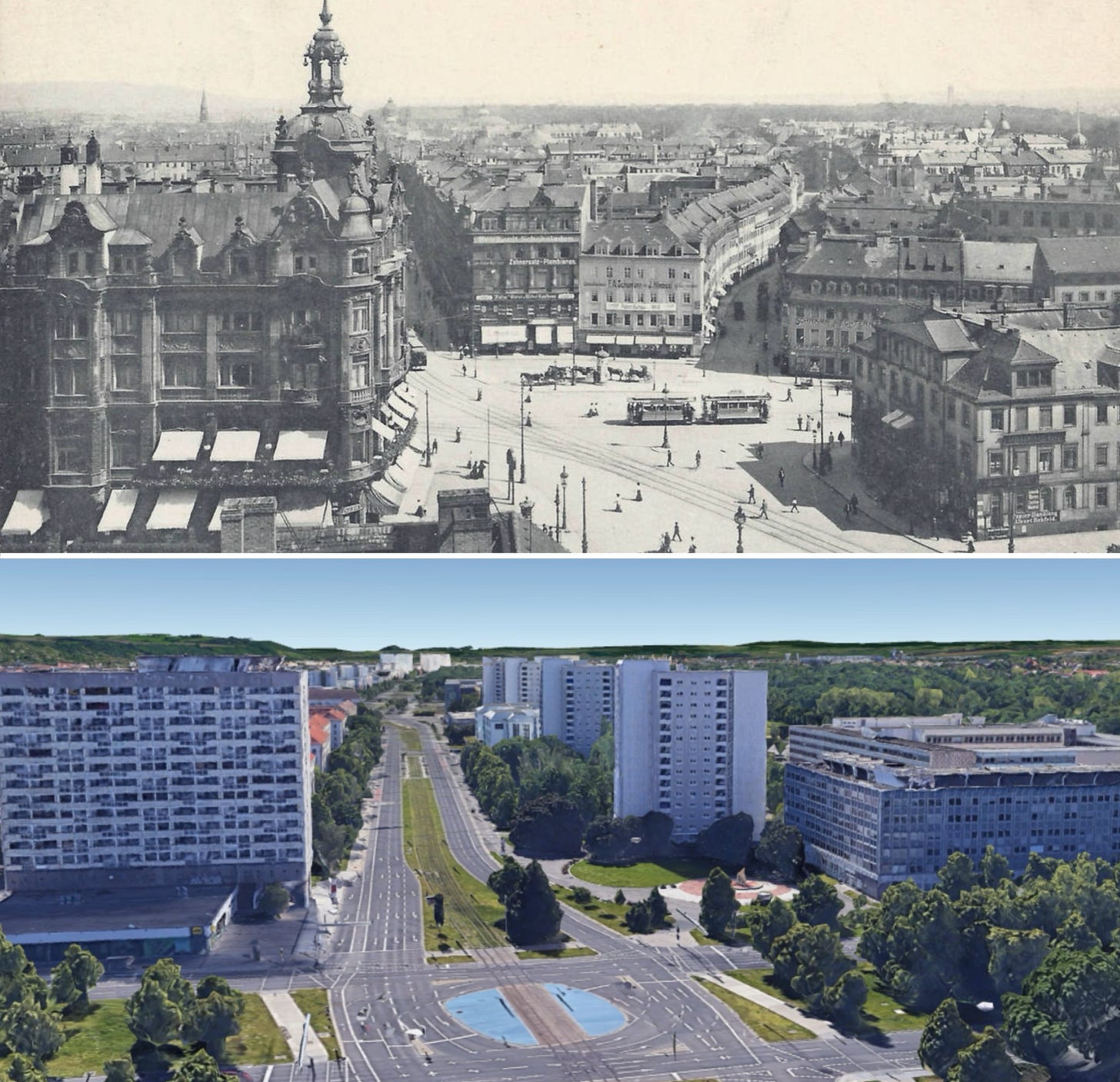

Punishment by Architecture

The USSR had suffered greatly at the hands of Nazi forces. Now, controlling almost half the country, the Soviets finally had their chance to retaliate.

They began by punishing ordinary German citizens according to the penalties laid out for Nazi officers in the Potsdam Conference, including confiscating their lands. They then demanded further remuneration from citizens, despite the fact that the Allies’ peace treaty specifically left out financial recompense to avoid impoverishing the country again.

The Soviets then jumped at the opportunity to remodel Dresden from its war-time rubble into a model city of socialism. But perhaps most cruelly of all, the regime forced Germans to leave their beloved Frauenkirche in ruins.

The ostensible purpose of this diktat was to honor the damage as a memorial of the war’s suffering — a reminder of war’s incalculable costs. But more likely, it was ordered for the same reason the Frauenkirche was destroyed in the first place: to break the spirit of the people.

Glory from the Ashes

For fifty years, the Frauenkirche lay in the dust. Then, in 1989, a clerical error changed the modern world.

The Soviet government issued an order to slightly loosen travel restrictions across the Berlin Wall, but the official who announced it to the public misunderstood the command. Instead, it was announced that all restrictions would be removed, which implied Germany would be reunited. Within hours, rejoicing crowds stormed the Wall. Within the day, it fell.

Over the next two years Germany was reunited, and German citizens went to work healing half-century-old wounds — including the devastation in Dresden. In 1993, work began on the Frauenkirche.

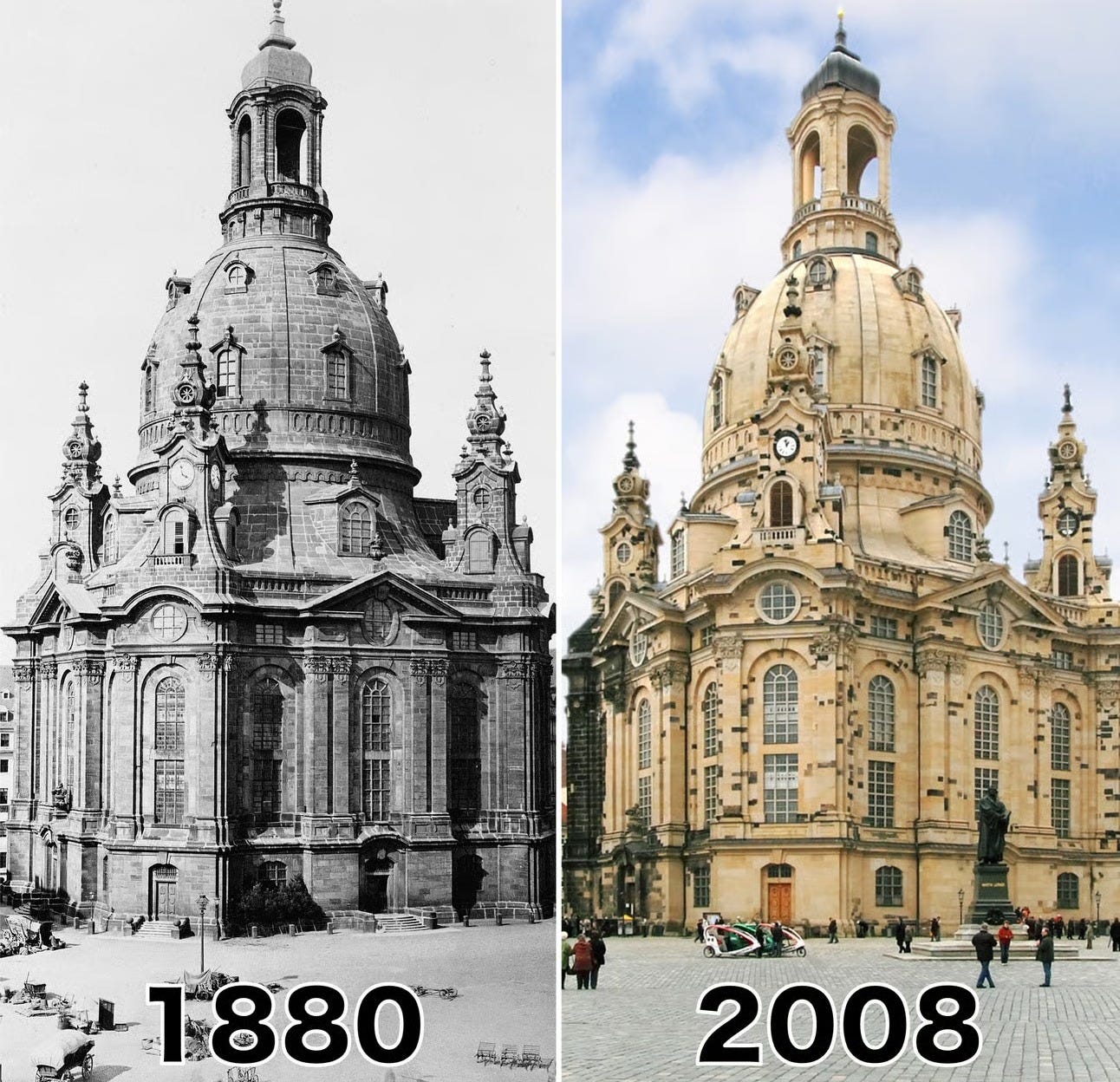

It would have been easy for short-sighted project managers to commission a new design for the church with concrete walls and intersecting glass planes. But incredibly, that’s not what happened. Instead, workers approached the bricks that had lain in dust for fifty years, and carried off every piece that could be salvaged for analysis. They then began a twenty-year labor of love — reconstructing the church from its original stone, literally brick by brick.

Builders pored over old photographs and paintings of the original structure, and painstakingly drafted plans based on its former dimensions. Using as much original material as possible, they began building it back precisely as it once was. After fifty years, the Frauenkirche rose again.

Sadly, the church’s golden dome could not be remade, so a new one was built. But even in this detail, imaginative designers found meaning: the dome was topped by a golden orb and cross forged by an English goldsmith, the son of a pilot who had taken part in that devastating firestorm of 1945.

Rebuilding Peace

Architecture can be a touchstone of culture, an anchor of community, and a wellspring of beauty. But it can also be a tool of totalitarianism, a pawn of politics, or a jackboot of oppression.

The revival of Dresden is more than just a story about an insightful rebuild: it exemplifies the power of culture to build beauty, and of beauty to build culture. For while the USSR relished in razing beautiful monuments and erecting brutalist ones, the German people’s love of history raised a miracle from a pile of rubble.

In turn, the beauty of the Frauenkirche became an occasion for reconciliation — bringing together even the children of enemy combatants to complete it…

Thank you for reading!

Remember, you can support us and get members-only content every weekend — great literature, art, and philosophy breakdowns.

Paid readers can access our *entire* archive of premium articles right here.

In the last year, we’ve written about everything from Dante’s Divine Comedy, to the history of the Eternal City of Rome, to the coded messages in Leonardo da Vinci’s art…

This Saturday, we’re looking closely at William Golding’s “Lord of the Flies” — to understand what it reveals about the nature of fear, paranoia, and man’s innate capacity for evil…

People can destroy the physical, but the spirit cannot be destroyed so easily.

A well written and informative piece about the power of architecture in its ability to punish but also in its ability to unite.