How Dark Were the Dark Ages?

And why progress isn't inevitable

“The dark ages weren’t dark!” is a popular refrain on social media these days. Such sentiments often accompany a picture of a beautiful cathedral or the interior of Sainte-Chapelle in Paris, with users commenting to ask why academia conspired to ever call these the “dark ages”.

To support this popular cause, a history book entitled The Light Ages was published in November 2020, followed by another (somewhat less creatively) entitled The Bright Ages in 2021. Both books push back against the commonly-held view that the Medieval world was backwards and anti-intellectual, showing why the middle ages were never dark at all. Finally, justice for lovers of history!

Or so it seems. Because while movements to do away with the term “the dark ages” purport to depict the medieval world as it really was, they in fact distort it like never before. Often, there are political motives for doing so. The “dark ages” were in fact dark, and the desire to portray them as otherwise is, at best, dishonest — at worst, sinister.

That said, the “dark ages” aren’t what you think they are, and don’t apply to the entirety of what we now call the middle ages. Today, we look at what the dark ages actually were, why they really were dark, and why there is a concerted effort to reframe them as otherwise…

Reminder: this is a teaser of our members-only deep dives.

To support our mission and get exclusive content every week, upgrade for just a few dollars per month. You’ll get:

New, full-length articles 2x per week

The entire archive of content (150+ articles, essays, and podcasts)

Membership to our bi-weekly book club (+ subscriber chat room)

Our book club is about to start reading J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Fellowship of the Ring! The first discussion is on Wednesday, November 19, at noon ET — join us!

History of a Phrase

The 14th-century Italian poet Petrarch is often cited as coining the term “the dark ages”, despite a lack of evidence suggesting he really did. More likely, he popularized a pre-existing term already in circulation — more on the significance of this later.

But while the phrase has its origins in continental Europe, it is today primarily an English term, lacking a proper equivalent in most other European languages. This is partially due anti-Catholic sentiment in the wake of the English Reformation, with the term being co-opted to further the narrative of the European continent being a backwards and obscurantist world under the popes.

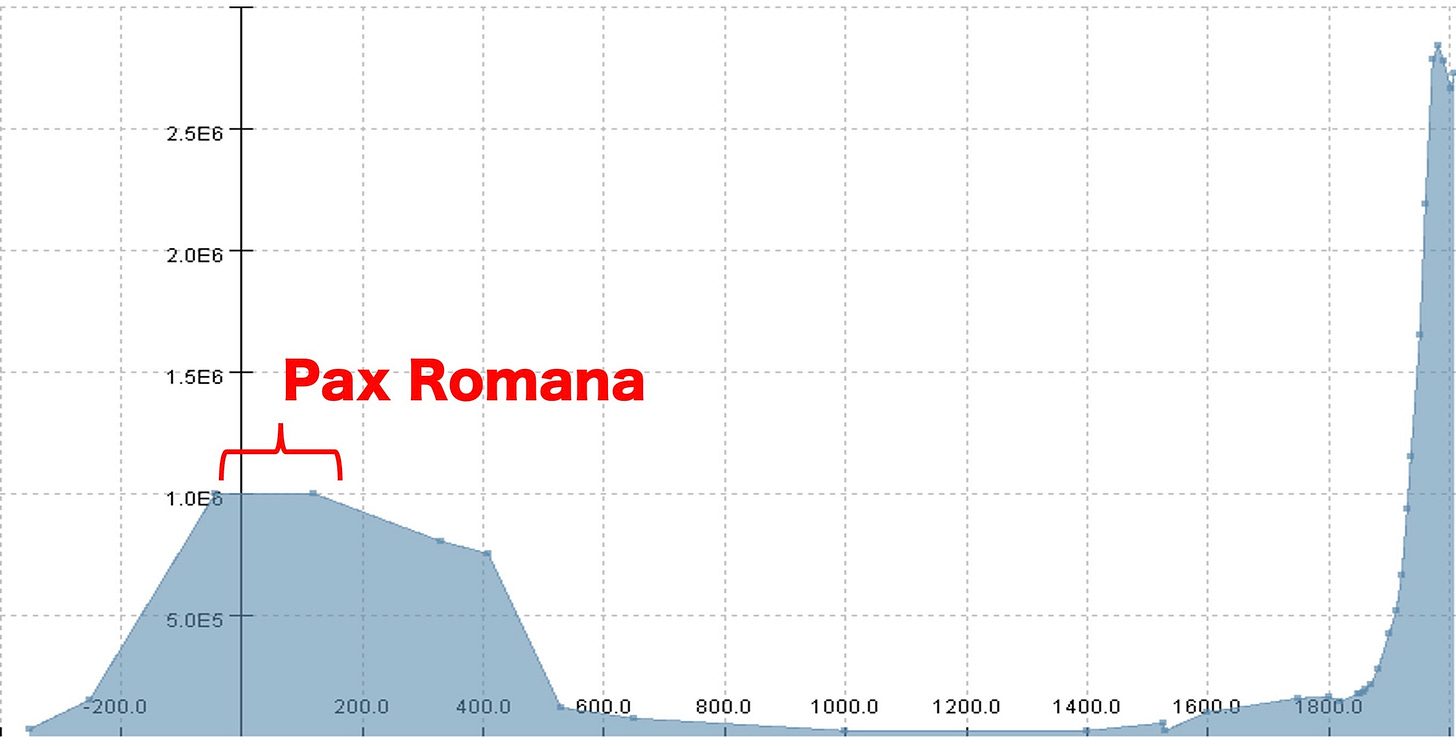

Today, the term is often used to refer the period from about 400-1400, or in the words of the 1883 American Cyclopaedia, “that period of intellectual depression in the history of Europe from the establishment of barbarian supremacy in the fifth century to the revival of learning about the beginning of the fifteenth”. While the starting point is correct, the end point is wrong: the true “dark ages” surely don’t encompass the world of Sainte-Chapelle, Thomas Aquinas, and Dante Alighieri (all 13th century).

So when, then, did the dark ages really end?

Serious scholars look to the 11th century with the Gregorian reforms and the founding of the first university, or even earlier to the 8th and 9th century’s Carolingian Renaissance. Either way, the period of roughly 1000-1300 AD — known as the “High Middle Ages” — was decidedly not dark. But that still leaves us with 400-500 years following the fall of Rome which, still in Petrarch’s day, was remembered as a period of darkness.

But just how dark did it get? That’s what we look at next…

A Lost and Foreign World

In modern Italian, a term like il settecento (literally: “the 700s”) refers not to the 8th century, but to the 18th. Even professional Italians historians use this phrase, and the reason is simple: there was so little happening in the 8th century, they say, that of course they wouldn’t be referring to it.

This linguistic tidbit points to a deeper reality: that following the fall of Rome, very few events of consequence actually happened. Or at the very least, they’re not recorded as happening

What historians of Ancient Rome or Greece take for granted, historians of the actual dark ages dream of being privy to: basic things like names and dates are disputed, and locations of major events are impossible to pin down. The few concrete sources that do exist are often copies of copies, scarcely original and seemingly derivative of some older, more thorough, and more substantial text.

But a paucity of primary sources is not the only thing which categorizes the period. While European society didn’t literally go backwards, it did literally get smaller: from the size of buildings to the size of cattle, early medieval society existed at a smaller scale than its ancient predecessors. This went hand in hand with a general population decline across the continent — even the city of Rome itself would not return to its 2nd century population levels until the 1930s under Mussolini.

Literacy was markedly worse than it had been centuries prior, and even the few “lights” of the period stand either towards the beginning of it — like Boethius and Saint Augustine of Hippo — or towards the end of it, like Alcuin of York. The few standout thinkers that lived plainly in the middle of it, like the Venerable Bede or Pope Gregory the Great, are notable exceptions that prove the rule of the otherwise widespread intellectual poverty.

So why then, are English-speaking academics suddenly rushing to cover up these real dark ages by portraying them as more flourishing and enlightened than they really were?

Most of the time, it almost always comes down to one hot-button issue…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Culturist to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.