How to Conquer the 7 Deadly Sins

Dante's guide to self-mastery

Previously we explored Dante’s Inferno, the first canticle of his three-part Divine Comedy. While Inferno is certainly the most popular of the three, the other two, Purgatorio and Paradiso, are just as insightful.

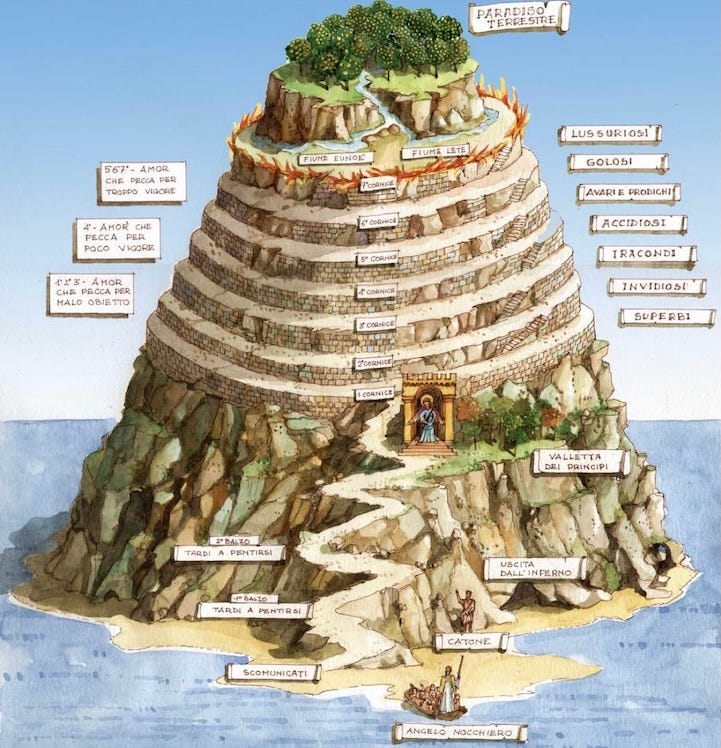

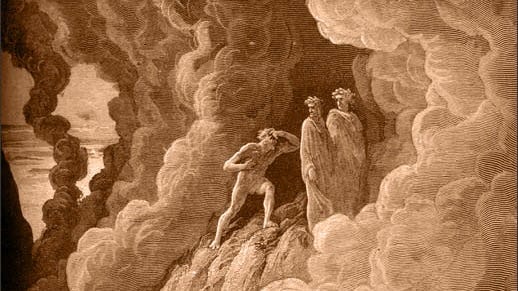

Purgatorio is particularly fascinating. It begins with Dante emerging from the depths of Hell and casting his eyes on Mount Purgatory, a mountain composed of 10 terraces, with the middle seven corresponding to each of the seven deadly sins. As Dante climbs it, he metaphorically gets purged of each sin, and on each terrace learns a lesson about virtue and vice that is essential for spiritual salvation.

These lessons on salvation, however, are just as applicable as archetypes of self-improvement. For example, the climb is most difficult at the lower terraces, but becomes easier as you ascend — personal development, much like climbing a mountain, becomes more manageable as one practices new habits of virtue.

Whether you approach Purgatorio from a spiritual or secular perspective, the canticle is a rich fount of insight. Here’s what it reveals about self-development, and how the archetypes Dante uncovers can help you on your own journey…

A Big Update!

Today, we are starting a brand new sister publication: The Ascent.

We started The Culturist to be an exploration of historical wisdom across a broad range of disciplines, from art history to ancient philosophy. We’ve also covered theological topics here, from the mythic worldview of Tolkien to Dante’s tips for reading the Bible.

Now, we want a new space to go further in this direction — this email on Purgatorio is a teaser of the kind of things we have coming.

The Ascent will dive into theology, mysticism, and ancient texts. We’ll study the ideas, history, and revolutionary teachings from 2,000 years of the Christian imagination, and how they can help the modern reader (Christian or not) ascend to the divine.

Expect short essays on everything from Moses' ascent of Mount Sinai to Plato's ladder of love, from the secret of the Book of Jonah to the spiritual dangers of technology, and from the role of paganism in Christian education to the mysteries of Dante.

One free article every Tuesday, and longer deep dives every Friday for paid readers…

The Structure of Mount Purgatory

The mountain of Purgatory is composed of 10 terraces: one “pre-Purgatory” terrace at the bottom, then seven corresponding to the seven deadly sins, and two final terraces where the Earthly Paradise is found.

The terraces corresponding to the seven deadly sins are split into three categories: sins of perverted love, deficient love, and misdirected love. The first three deadly sins of pride, envy, and wrath constitute perverted love, acedia (sloth) constitutes deficient love, and finally, greed, gluttony, and lust constitute misdirected love.

Because the mountain is hardest to climb at the lower terraces, there’s already a lesson here: overcoming pride is the key to overcoming all other vices. Only by first overcoming pride can you begin to overcome envy, only by overcoming envy can you overcome wrath, and so on and so forth.

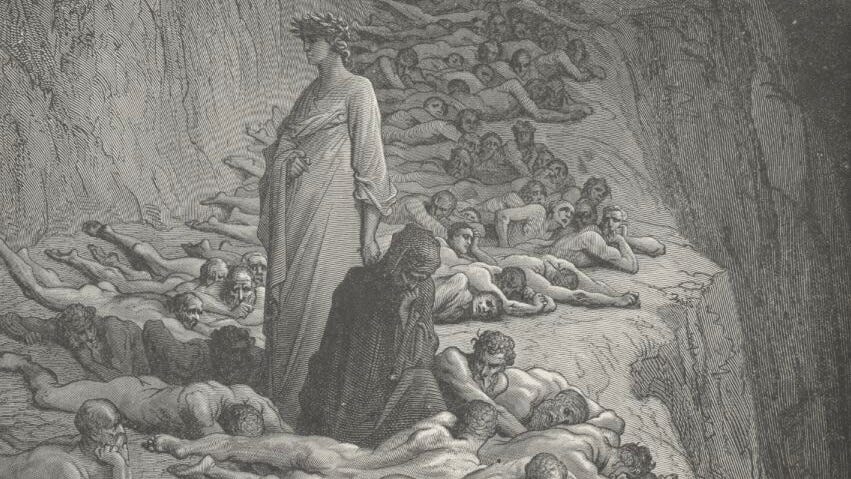

Pre-Purgatory

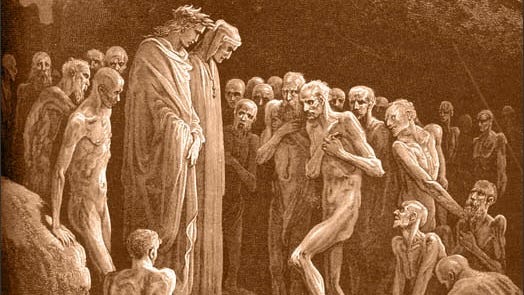

Setting out on their journey, Dante and his guide Virgil first encounter souls waiting at the base of the mountain. These are people who were excommunicated by the Church or were late to repent in life (and did so at the last minute). Before they can enter Purgatory, they must wait here for a time corresponding to their transgression — for the late-repentant, the waiting time is equal to their entire lives on Earth.

Once this is over, souls pass through the Gate of Purgatory, opened by an angel wielding the keys given to Saint Peter by Christ. There’s not one key, but two: a silver key representing the sinner’s remorse, and a gold one representing God’s grace. If the soul approaching is not truly sincere in his contrition, their key will not turn…

The Terraces of Perverted Love:

1. Pride

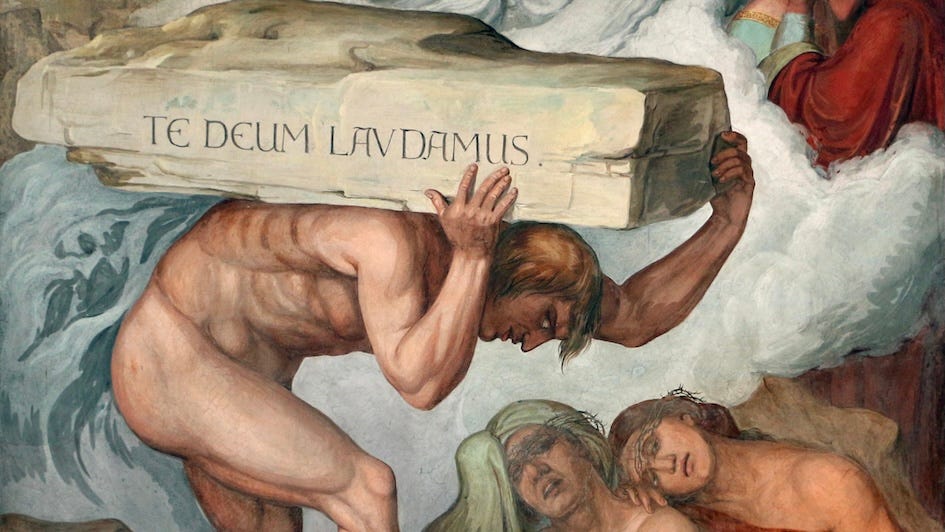

The first level of Purgatory proper is where you must conquer pride. In Dante’s depiction, souls on this terrace carry heavy boulders, symbolizing how pride weighs individuals down and impedes progress.

This imagery illustrates the dual consequences of pride: it not only slows down personal achievements, but the colossal size of a boulder also (literally and metaphorically) blinds individuals to self-awareness and the broader perspective necessary for growth.

As for practical approaches to overcoming pride, Dante suggests a focus on its opposite and corresponding virtue: humility. By using the example of a prideful soul who, in the very midst of saying something prideful, stops himself and redirects course, Dante emphasizes the importance of self-awareness and vigilance in remedying the sin of pride.

2. Envy

On the next terrace of Purgatory, Dante encounters the souls of the envious. To be clear, envy extends beyond mere covetousness — it is an intense resentment towards others for possessing things one does not have.

How do you cure envy? Souls on this terrace have their eyes sewn shut — the cure is a fixed focus inward rather than on external desires, and the triumph of self-reflection over external comparison.

Dante suggests that the opposite and corresponding virtue to envy is generosity, and makes clear that by becoming more generous, one can better overcome it.

3. Wrath

The final terrace in the grouping of perverted love is for wrath. Dante defines wrath not as mere anger, but as a defensive, harmful reaction characterized by blindness and disorientation, which prevents individuals from seeing the bigger picture in life situations.

The souls on this terrace are depicted wandering blindly in acrid smoke, symbolizing the blinding rage that wrath induces, and again echoing the themes of blindness associated with the previous sins of pride and envy.

The corresponding virtue to wrath is gentleness, and as souls depart the terrace of wrath a Beatitude is proclaimed: "Blessed are the peacemakers." Dante highlights the importance of calm-headedness and non-escalation as means of overcoming wrath, and consequently continuing one’s journey up the mountain of Purgatory.

The Terrace of Deficient Love:

4. Acedia

Next are those who failed in life to take action in the pursuit of love. Acedia, commonly known as sloth, is distinct from mere laziness: it is instead a profound indifference and lack of care about beauty, morality, and action. Acedia has both societal and personal repercussions.

On a societal level, acedia manifests as indifference to justice and communal responsibilities. On a personal level, it results in a life characterized by a lack of excitement, joy, and wonder, which often leads to depression.

Zeal is the opposite and corresponding virtue to acedia, and on this terrace souls are made to observe depictions of passionate, zealous individuals: The Virgin Mary is depicted joyfully proclaiming the Magnificat, and Dante also provides examples from the life of Julius Caesar.

The cure to acedia, then, seems to be rooted in taking inspiration from others: Dante highlights the necessity of looking to the greats who have before, who you can learn from and be inspired by their zeal for life.

The Terraces of Misdirected Love:

5. Avarice

Avarice is referred to as “greed” in common parlance — but while greed is typically focused on riches, avarice is characterized by the insatiable desire not just for money but also for success and other ambitions. It promotes short-term gains over long-term success, and persuades those in its grasp to push ethical boundaries for personal gain.

The souls on this terrace lie face-down in the dirt, symbolizing their earthly material focus. However, their posture also represents the virtue opposite to avarice that they are being taught on this terrace: that of submission and service.

Whereas avarice leaves one never fully content, serving others leads to true contentment and satisfaction. Hence the Beatitude Dante selects for this terrace: "Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they shall be satisfied."

6. Gluttony

Dante defines gluttony not just as an excessive craving for food, but as an overindulgence in comfort — in today’s world, it would include behaviors like watching pornography, or binge-watching Netflix.

What Dante describes on this terrace are souls who walk around hungry and thirsty, and all around them are trees full of fruit. However, every time they reach out for the actual fruit, they're unable to grasp it.

The scene symbolizes those who never forewent comfort in their lives. Every time they wanted something, they could easily reach for it and obtain it. So now they must learn the necessity of foregoing comfort, even when it is quite literally at your fingertips.

As a remedy for gluttony, Dante puts forward the virtue of temperance. He highlights biblical examples of Daniel and St. John the Baptist, who both epitomize the denial of comfort to attain spiritual wisdom and growth. The lesson? To achieve higher aims, you must avoid immediate gratification.

7. Lust

Lust is the final sin that must be overcome before souls are allowed to pass on through the Earthly Paradise, and then into the realm of Heaven itself.

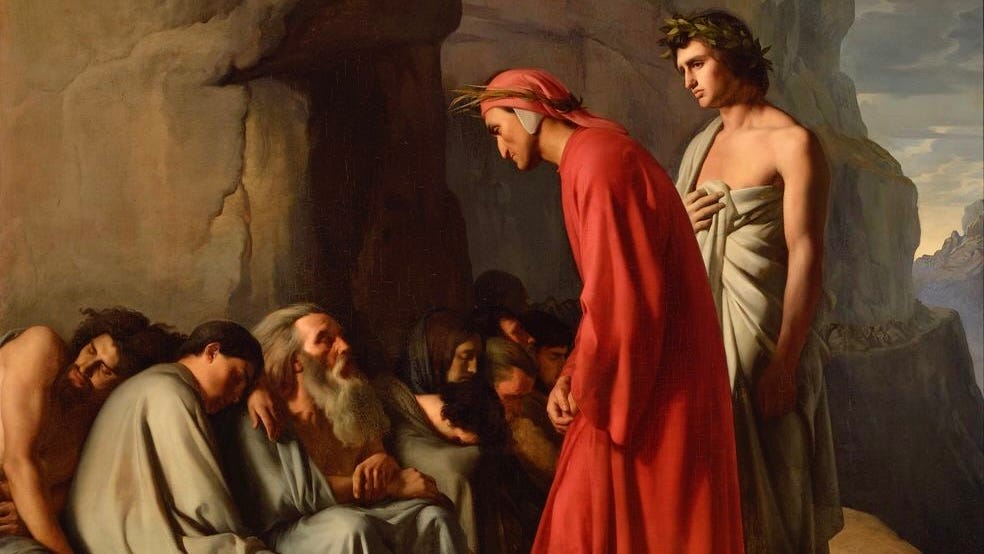

Before leaving the terrace, souls must pass through a cleansing fire. When Dante first sees it, he’s terrified. His guide Virgil reasons with him, reassuring him that all will be okay: “Don’t worry, God has willed this! Don’t you remember we passed through Hell together, and came out safe even from there?”

Dante, however, is not convinced. Until, that is, Virgil mentions something else: the name of Beatrice. Upon hearing the name of his beloved, Dante loses all doubt: he will do anything for Beatrice, including passing through a wall of fire!

The lesson here applies not just to the final terrace, but to all of Purgatory itself: to overcome sin and pass through the purging fire, you must be motivated by love.

To put that in secular terms, it is love that drives self-improvement. You don’t successfully lose weight, for example, by hating how you look — you do so by falling in love with the future that being in shape will offer you.

The same goes for lust: to conquer it, you must first fall in love with something higher.

Earthly Paradise

Finally, Dante reaches the summit: the Garden of Eden. He has recaptured the state of innocence that existed before Adam and Eve fell from grace, and now, untethered by sin, may begin his ascent to Paradiso (the next section of the poem).

Without first venturing through Purgatory, Dante would be incapable of ever entering into Paradise. The same goes for us on our journey to whatever our “Paradise” is — whether that be a literal one (Heaven), a metaphorical one (our desired goals and success), or both.

The archetypes of self-development Dante uncovers during his trip through Purgatory have much to teach us about what is required to attain Paradise. In this, the transformative power of great literature is revealed: over 700 years after its writing, Dante’s Divine Comedy still has the capacity to change the hearts, minds, and lives of those who read it today…

Thank you for reading!

If you’re interested in reading more emails like this, you must check out our brand new sister publication, The Ascent. There, we are diving deeper into theology, mysticism, and ancient texts…

One free article every Tuesday, and longer deep dives every Friday for paid readers:

I’m saving this blog for future reference!

Very illuminating, as usual. Interesting that our "president" has committed all of the 7 Deadly Sins and violated the 10 Commandments, yet his followers consider him pretty darn close to a deity.