How to Find True Love

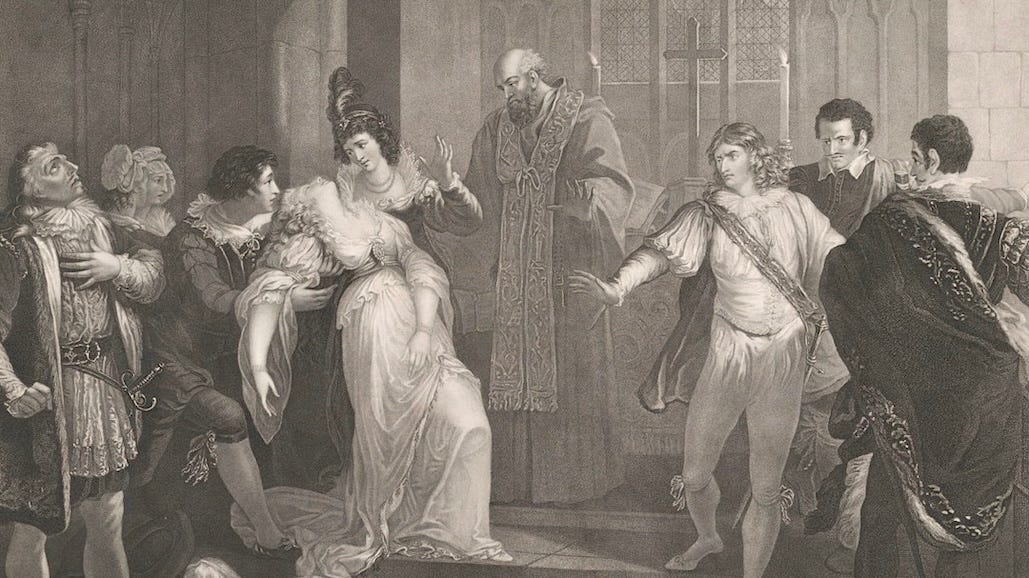

Shakespeare's "Much Ado About Nothing"

Finding love is a cultural obsession unlike any other. Seemingly every other film, novel, poem, and song is about falling in love. Whether they know it or not, influencers make millions of dollars each year teaching their followers how to find love — because at some level, every element of finance, fitness, or fashion advice is about becoming your best to attract a mate.

But amidst all of this relationship advice, people are lonelier than ever. Although the extent of their loneliness is aggravated by modern phenomena, the causes of it are the same as they were hundreds of years ago.

Specifically, there are two extremes that people often fall into while approaching relationships — and each one is destined for failure.

Shakespeare explored these two extremes in his play Much Ado About Nothing, which was first performed in 1600. In it, two comic bachelors with flawed understandings of love bungle their way through their respective relationships before finally arriving at “happily ever after”.

Along the way, Shakespeare highlights the folly of these two approaches, demonstrating why they’re destined to leave you miserable. But even better, he also reveals the key to reconciling them in order to tread the middle path and find lasting love.

Today, we explore these two failed approaches to romance, and Shakespeare’s insight on how to truly be happy in your relationship…

Reminder: this is a teaser of our members-only deep dives.

To support our mission and get exclusive content every single week, upgrade for a few dollars per month. You’ll get:

Full-length articles 2x per week

The entire archive of premium articles and podcasts

Membership to our bi-weekly book club (+ subscriber chat room)!

Our paid subscriber Great Books Club is currently reading Milton’s Paradise Lost. The next meeting is on Wednesday October 8, at noon ET — join us!

The Despair of Cynicism

The two main couples in Much Ado About Nothing are Claudio and Hero, and Beatrice and Benedick. The plot revolves around the former couple, but it is undoubtedly the latter who steal the show.

Beatrice and Benedick have each sworn off love. To them, a relationship — and marriage in particular — signifies a loss of independence and individuality, among many other things. Beatrice swears she’ll never marry, and Benedick declares his intent to remain a lifelong bachelor. In the play’s opening scene, he declares:

That a woman conceived me, I thank her;

that she brought me up, I likewise give her most

humble thanks…

Because I will not do them the wrong to mistrust

any, I will do myself the right to trust none. And the

fine is, for the which I may go the finer, I will live a

Bachelor.

-Much Ado About Nothing, Act I, scene 1

To this, Benedick is met with the reply “I shall see thee, ere I die, look pale with love.” But instead of conceding, he doubles down:

With anger, with sickness, or with hunger,

my lord, not with love. Prove that ever I lose more

blood with love than I will get again with drinking,

pick out mine eyes with a ballad-maker’s pen and

hang me up at the door of a brothel house for the

sign of blind Cupid.

Throughout the opening scene, Benedick’s cynicism towards love is unmistakable: he likens marriage to cuckoldry, and can’t get over the apparent loss of independence it entails. To him, women weaken a man’s will and hold him back from doing all that he can or ought to do.

Beatrice, though for slightly different reasons, largely echoes Benedick’s sentiments — and when they finally encounter each other, the verbal sparring begins:

Beatrice: “I had rather hear my dog bark at a crow than a man swear he loves me.”

Benedick: “God keep your ladyship still in that mind! So some gentleman or other shall ‘scape a predestinate scratched face.”

Beatrice: “Scratching could not make it worse, an ‘twere such a face as yours were.”

The sad thing is, everyone but Beatrice and Benedick can see that the two would be perfect for each other, if only they could get over their pride and cynicism. Their negative perspective on relationships keeps them from experiencing something great, and breeds a silent resentment in them when they see others who are happily in love.

Eventually, however, they end up together, and Shakespeare playfully details how it all happens — but not before showing us the other extreme approach to love…

The Folly of Romanticism

As the counter to Benedick’s cynicism, Shakespeare presents Claudio, a dashing young soldier. He is the returning hero from the war, and is described by a messenger as such:

He hath borne himself beyond the promise of his age, doing in the figure of a lamb the feats of a lion.

-Much Ado About Nothing, Act I, Scene 1

But unfortunately for Claudio, all of his actions will later be undermined by one of his lamentable defects: that of rushing blindly into relationships.

Upon seeing the young woman named Hero for the first time, he describes her as “the sweetest lady that ever I looked on”. Nearly 60 lines later, he proclaims that he loves her. But while Benedick’s cynicism prevents him from taking part in something beautiful, Claudio’s overromanticism of Hero takes what could have been beautiful, and sullies it.

Claudio puts Hero on a pedestal and creates an idyllic image of her in his mind, never truly getting to know her but only his idea of her. This leads to disaster when another character tricks Claudio into thinking Hero cheated on him, and because the foundations of Claudio’s romantic world aren’t moored in reality, everything soon comes crashing down around him.

On their wedding day, Claudio denounces Hero at the altar, publicly humiliating her and making a fool of himself in the process. Had he actually gotten to know Hero, he would have known that she never would have cheated on him — but because he only ever loved his romanticized notion of her, it was only too easy for him to exchange one false vision for another. Things eventually heal between the two lovers, but not before a good deal of repentance and soul searching on Claudio’s end.

Throughout the course of the play, Shakespeare uses the words and deeds of Benedick and Claudio to carefully demonstrate the two main dangers you face when approaching love: being too cynical, or being overly romantic.

But how does he suggest you tread the middle path between them?

In an often-overlooked moment from Act II, Scene 3 of Much Ado, Shakespeare throws in a line that reveals how to do precisely that. It’s the key to Benedick and Claudio getting their relationships back on track, and to this day remains a valuable piece of advice for finding and staying in love throughout the years.

It all has to do with viewing both the magical and the mundane aspects of love together, and not getting misled by either…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Culturist to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.