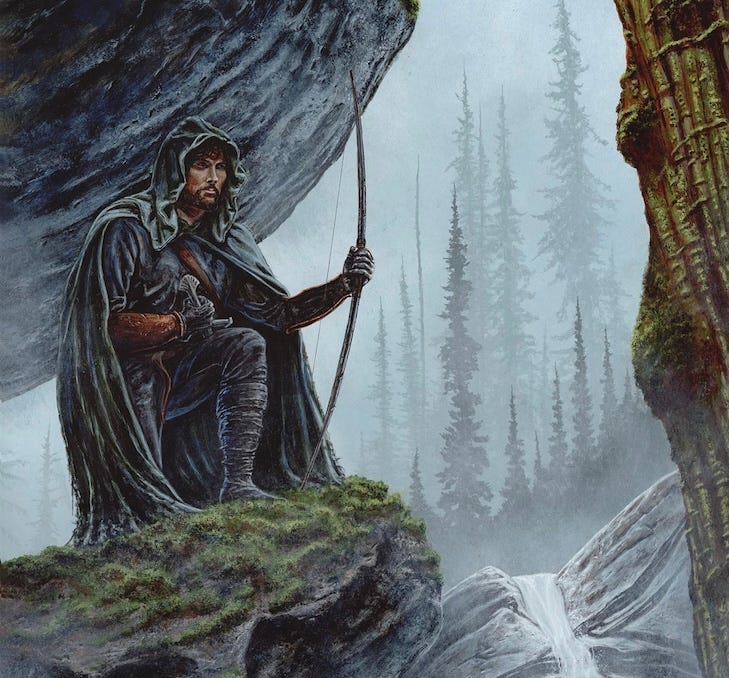

How to Live Through a Great Decline

Tolkien’s answer for when hope runs out

If you’re living through a great decline, how should you personally live and act in the midst of it?

This is the question at the heart of J.R.R. Tolkien’s 1954 masterwork, The Lord of the Rings. Middle-earth is marred by civilizational decline, the loss of hope among men, and a profound sense that the beauty of the past is doomed to decay. This slow fading was the author’s attempt to express something he had felt all his life, which he once described as a “heart-racking sense of the vanished past.”

As we read in his letters, Tolkien also interpreted real human history in this way: a steady fading of the beauty and magic of creation.

I do not expect ‘history’ to be anything but a ‘long defeat’ - though it contains (and in a legend may contain more clearly and movingly) some samples or glimpses of final victory.

Yet the Professor’s storytelling is the opposite of doom and gloom. In fact, it offers one of literature’s most compelling answers to enduring an inevitable downfall.

If living through an age of decline is indeed your own destiny, there is more than enough reason to face it forthrightly, even — and especially when — all hope has disappeared…

Thank you for reading! If you’d like to support our work, please consider taking out a paid subscription — it helps us enormously. Plus, you’ll get:

New, full-length articles 2x per week

The entire archive of content (180+ articles, essays, and podcasts)

Membership to our biweekly book club (and community of readers)

The Death of Boromir

We begin to see the answer to the “long defeat” in the events following the death of Boromir. After Boromir gives his life to save the Hobbits from Saruman’s Orcs, the Fellowship lies in tatters. With time against them, Merry and Pippin being swept away by the enemy, and Frodo passing out of their control, Aragorn and company make a decision that seems strange.

They pause to mourn Boromir’s passing with a proper ritual.

To many readers, this feels entirely reckless. Their “best” course of action is surely to prioritize what is most urgent: that the fate of their quest hangs in the balance. We recognize that, in any “normal” context, it would be wrong to let Boromir’s body lie out in the open. But the nature of their mission surely doesn’t allow for the luxury of a funeral — right?

But the fact that abandoning Boromir’s body is wrong in normal times is precisely why it is wrong even now. At the heart of The Lord of the Rings is the idea that moral decisions lie beyond their immediate context. Some things just are wrong and others right, and once context becomes an arbiter of that distinction, you’ve lost your grip on what it means to be good.

At its core, this worldview is deontological: ethical decisions should be made according to a set of universal principles, not the consequences of each decision. This is famously elaborated in the ethical theories of Kant, who believed that morality is grounded in our rational duties to one another, and all humans are inherently worthy of this dignity. Boromir is worthy of a funeral rite, and so it is the Company’s duty to provide it.

But something else then happens. Aragorn makes yet another decision to halt progress on the greater mission in favor of that which speaks directly to his heart:

“I would have guided Frodo to Mordor and gone with him to the end; but if I seek him now in the wilderness, I must abandon the captives to torment and death. My heart speaks clearly at last: the fate of the Bearer is in my hands no longer.”

He will pursue Merry and Pippin, rather than sacrifice them for the “more important” quest. This decision is underpinned by something else crucial to the story’s ethical framework: Tolkien’s heroes recognize they are not in control of everything…

The Anti-Great Man Theory

Aragorn cannot force the Ring to be unmade through his own will to power, and he’s aware that the universe — and the fate of the Ring — is guided by forces beyond his own and of his enemies. His decisions are all made in that humility.

This stands in opposition to what we might call the “Great Man Theory,” the idea that history is shaped by the will of a few exceptional figures: “The History of the world is but the Biography of great men.”

This theory was popularly held at the time Tolkien was writing, and Middle-earth is itself a story of exceptional heroics — but there’s a difference. Even Middle-earth’s kings recognize that they themselves play only a small part in the grand story.

When Frodo breaks away from the Company, it seems Aragorn is pushed out of the central quest altogether. He comes to terms with the fact that he cannot control Frodo’s fate, yet this only sharpens his focus on what he can control. Saving Merry and Pippin may not play a part in the arc of history, but it is in service of the good, and so worthy of his attention all the same.

Norse Courage

Throughout Tolkien’s epic, again and again we see a kind of “Norse courage,” a reckless bravery that stands firm to its principles in the face of all odds. To die with this form of courage is to win a certain immortality, and it’s something that Tolkien absorbed from Norse myth and Old English tales like Beowulf.

The Defense of Osgiliath, the Battle of the Black Gate, and a hobbit contending with the might of Sauron are hopeless, unwinnable endeavors. And yet, none of them is a cause for despair for the heroes living through them.

The commitment to one’s duty even when the battle is lost resonates with all of us, but it’s another thing to have the courage to actually live (and die) by a code so strict. It’s easy to support the idea in principle, but how can we readers find the courage to live this way in our own lives?

Fortunately, Tolkien does not fail to answer this question. The answer is hiding in one of the most insightful sentences of the entire trilogy, as well as in a new concept proposed by the author.

This concept is an Elvish one, and it’s even more powerful than Norse courage. It’s what you turn to when all hope really does run out...

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Culturist to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.