How to Overcome Grief

C.S. Lewis on the problem of pain

Where is God? …go to Him when your need is desperate, when all other help is in vain, and what do you find? A door slammed in your face, and a sound of bolting and double bolting on the inside. After that, silence.

-C.S. Lewis, A Grief Observed

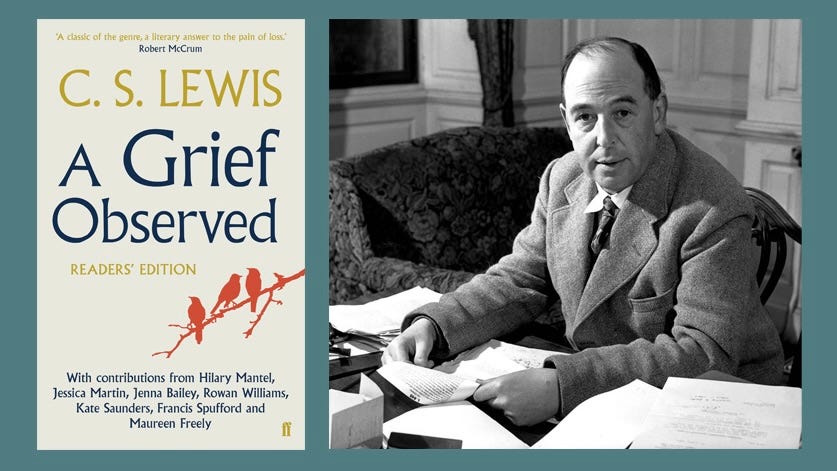

The question of why God allows suffering has been posed by both believers and atheists alike for centuries. That’s why in 1940, C.S. Lewis set out to finally answer it with his book The Problem of Pain. In it, he offered a robust explanation of why a loving God exists even in a world filled with suffering.

But 20 years later, Lewis’s theory was put to the ultimate test. When his wife died, Lewis was forced to wrestle with the ideas he had previously outlined so deftly — but he found the practice much harder than the theory.

Originally published under a pseudonym, A Grief Observed is the work that resulted from Lewis’s anguish, a book compiled from the notebooks he kept following the death of his wife. In writing this work, Lewis discovered something that changed his entire understanding of God and the problem of pain.

Today, we explore Lewis’s journey through grief and what it can teach you about pain, lamentation, and love — and most importantly, where God is in the midst of it all…

Reminder: this is a teaser of our members-only deep dives.

To support our mission and get our premium content every week, upgrade for a few dollars per month. You’ll get:

Full-length, deep-dive articles every weekend

The entire archive of great literature, art, and philosophy breakdowns

Members-only podcasts and exclusive interviews

The Power of Pain

Before diving into Lewis’s work, it is important to note a small detail: the inclusion of the article “A” in the book’s title. This detail, like so many of those in Lewis’s writing, is intentional — it reminds the reader that the book’s contents do not presume to document the only way in which grief is experienced, but rather one specific experience among many.

That said, A Grief Observed is famous for its wide-ranging appeal and ability to connect with others who experience grief in different ways. Perhaps this is because the central concepts transcend the specific details of suffering itself — for example, one of the main themes is about how, throughout your life, your idea of God is repeatedly being shattered.

My idea of God is not a divine idea. It has to be shattered time after time. He shatters it Himself. He is the great iconoclast. Could we not almost say that this shattering is one of the marks of His presence?

-C.S. Lewis, A Grief Observed

The first “shattering”, Lewis states, occurred in the Incarnation, when God became man and united both divine and human nature in the person of Jesus. He goes on to write that one’s view of God is often shattered in private prayer — and so too, of course, in pain.

This shattering is ultimately a good thing though, because it destroys incorrect beliefs you have both about God and yourself; beliefs that keep you from becoming who you’re truly meant to be. In this sense, Lewis says that pain serves to capture one's attention — in The Problem of Pain, he originally phrased this idea as such:

God whispers to us in our pleasures, speaks in our conscience, but shouts in our pain: it is His megaphone to rouse a deaf world.

In A Grief Observed, however, Lewis’s tone shifts to better reflect what the sensation of this shattering feels like. Here he phrases it bluntly:

Man has to be knocked silly before he comes to his senses.

But of course, being “knocked silly” is a painful experience, and this experience can easily lead one to doubt God’s goodness. This is where Lewis insists on the importance of believing that “God hurts only to heal.”

To be clear, this does not mean that God himself causes suffering — but once a tragedy occurs, God sees you through it. In this sense, Lewis writes, God is like a battlefield surgeon, saving a man who, because of enemy fire, must now have his leg amputated in order to live:

The more we believe that God hurts only to heal, the less we can believe that there is any use in begging for tenderness. A cruel man might be bribed...But suppose that what you are up against is a surgeon whose intentions are wholly good. The kinder and more conscientious he is, the more inexorably he will go on cutting. If he yielded to your entreaties, if he stopped before the operation was complete, all the pain up to that point would have been useless.

Up to this point in the book, Lewis has primarily addressed only the emotional pain caused by grief and loss. But that pain, if not managed properly, leads to more anguish — it’s an anguish caused by despair, and is something Lewis comes to know only too well…

The Danger of Despair

No one told me that grief felt so like fear. I am not afraid, but the sensation is like being afraid. The same fluttering in the stomach, the same restlessness...

I dread the moments the house is empty.

-C.S. Lewis, A Grief Observed

Throughout A Grief Observed, Lewis makes no secret of his struggle with faith. He tries to turn to God, but feels as though God either isn’t there, or doesn’t care about him. In one moment of pain, he describes this frustrating struggle as such:

Why is [God] so present a commander in our time of prosperity and so very absent a help in time of trouble? I tried to put some of these thoughts to C. this afternoon. He reminded me that the same thing seems to have happened to Christ: ‘Why hast thou forsaken me?’ I know. Does that make it easier to understand?

As Lewis grows weary from this frustration, his pain slowly morphs into despair. This marks Lewis’s descent to the lowest point on his journey of grief, because while sadness can be endured, despair is what truly destroys you. The former is a passing emotion, but the latter is a declaration of terror — a statement that life is painful, irredeemable, and not worth living. This, in Lewis’s experience, is worse than not believing in God:

Not that I am (I think) in much danger of ceasing to believe in God. The real danger is of coming to believe such dreadful things about Him. The conclusion I dread is not ‘So there’s no God after all,’ but ‘So this is what God’s really like. Deceive yourself no longer’...

So how does Lewis handle the temptation to succumb to despair?

He begins by turning to an ancient and biblical response to suffering — and although counter-intuitive, it is ultimately what gets him through his grief, deepens his faith, and helps him to see the goodness of life itself…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Culturist to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.