As an increasing number of people today seek to encounter beauty in the world of classical music, they find themselves facing an unlikely enemy — the song titles.

Neither the galloping movements of Vivaldi’s Four Seasons nor the rousing choruses of Beethoven’s Ode to Joy are conveyed by technical titles like Violin Concerto No. 1 in E Major, Op. 8, or Symphony No. 9 in D Minor ‘Choral’, Op. 125. Because of this, breaking into classical music can often feel unnecessarily difficult.

Today, we want to remove those obstacles to help make classical music more accessible. We’ll look at everything from opus number to BWV, and make the world of classical a bit less intimidating — because access to a world of immense beauty should never be hindered by a naming convention…

Reminder: you can support our mission and get tons of members-only content for a few dollars per month:

Two full-length articles every single week

Members-only podcasts and exclusive interviews

The entire archive of great literature, art, and philosophy breakdowns

Types of Composition

The first purpose of classical music titles is to enable you to distinguish one composition from another without confusion. For example, a piano concerto vs. an opera.

Arguably the biggest distinguishing factor between two pieces of music is the type of composition. So whether it’s a symphony, sonata, concerto, or fugue, the type of composition is mentioned in the title right after the composer’s name — Beethoven’s 5th Symphony.

Since composers often write multiple compositions in the same form, “No. X” gets added to the title, and this almost exclusively follows a chronological order. For this reason, you can assume Beethoven wrote his Symphony No. 5 before his Symphony No. 9.

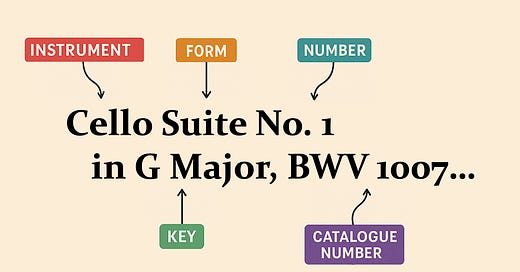

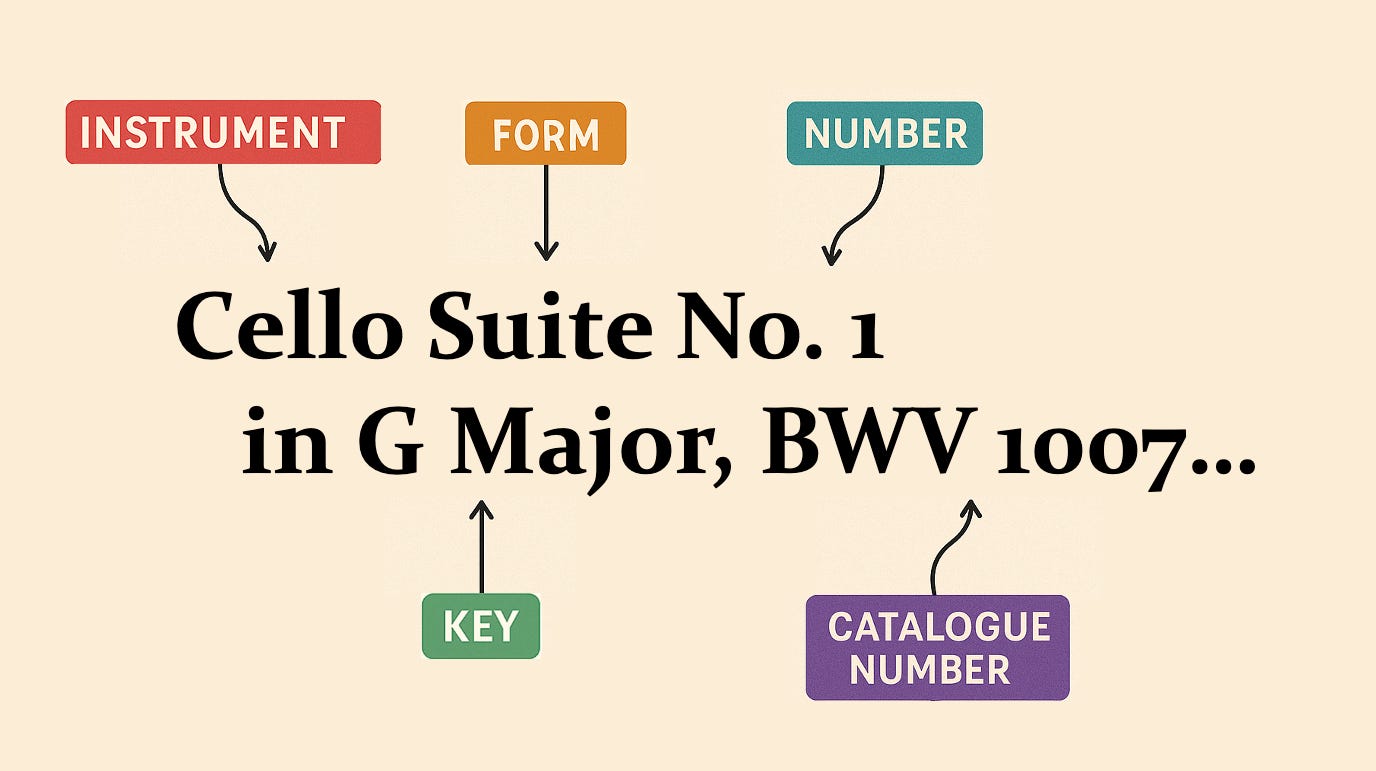

Instruments

Classical music pieces can be written for different musical instruments (such as piano or violin) or for vocal groups (as in choral music). While they don’t always have to be performed this way, it’s always helpful to know which instrument a work is written for.

For this reason, it’s common for classical music titles to contain the instrument in the title, like Bach’s Cello Suite No. 1 in G Major.

A good example of a composer who wrote music for various different instruments is Johannes Brahms. He wrote two piano concertos, one violin concerto, a double concerto for a violin and a cello, and several other complex works.

Keys

In addition to the composer, the composition type, and the instruments to be used, you need to know the key of a piece. The key is simply the musical scale the notes fit into, and it gets tacked onto the end of the title — Paganini’s Violin Concerto No. 2 in B Minor.

Although quite boring, the information presented here is quite practical. In this example with Paganini, the type of composition here is a concerto. It’s the second one he wrote, and is meant to be played on a violin in the key of B Minor.

Opus Numbers

The opus number is a number assigned to a particular composition. It serves as the “work number” and catalogs a composer’s work chronologically.

Opus number is abbreviated as Op. or op. To reference more than one opus, you use the abbreviation Opp. Since these indicate chronology, you can safely assume someone’s Op. 15 was written before their Op. 16.

The full generic name of almost every single classical music title includes an opus number — if you don’t see one, you’re probably just seeing an abbreviated title. A work like Symphony No. 5 in C Minor, Op. 67 gets referred to simply as “Beethoven’s 5th” in casual conversation.

On the rare occasion a work doesn’t have an opus number, it’s typically noted. In these cases, the term WoO is used. In German, it means “Werke ohne Opuszahl,” or “works without opus number.”

An example of a work without an opus number is Beethoven’s Für Elise, WoO 59.

Catalog Numbers

Everything up to this point is pretty straightforward. But what about those random letters included at the end of some classical music titles?

Famous composers like Bach, Vivaldi, and Mozart all had students of their work devise new and clever ways to organize and arrange their musical catalogs. These systems often follow their own internal logic, and aren’t organized chronologically.

For example, works by Bach usually add the abbreviation BWV. This stands for Bach Werke Verzeichnis, or Bach Works Catalog. It’s a system created by German musicologist Wolfgang Schmieder which catalogs Bach’s works by genre as opposed to chronology.

Similarly, Mozart’s works add the abbreviation K, which stands for Kochel Verzeichnis. Vivaldi’s works are assigned the letters RV, for Ryom-Verzeichnis.

For the average listener, these systems will never come in handy. But whenever you see a title like Cello Suite No. 1 in G Major, BWV 1007, you’ll at least understand why that last part is there.

Non-Generic Names, Subtitles, & Nicknames

As certain pieces of classical music started to become famous, they picked up some nicknames as they entered popular culture.

For example, you probably haven’t heard of Piano Sonata No. 14 in C-Sharp Minor, but chances are you know of Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata.

When classical music pieces have well-known non-generic names, they often get included in the title of a piece. Non-generic names may either have been added by the composer himself (in which case they’re called subtitles) or have been added by others including biographers (in which case they’re called nicknames).

A few works are known almost exclusively by their subtitles, like Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique or Strauss’s Also sprach Zarathustra. When writing out the full title of a piece, the subtitle or nickname is often appended to the end of a song title — for example, Mahler’s Symphony No. 2 in C Minor, Resurrection.

Music Tempo Markings

Classical composers frequently use Italian terms to indicate the tempo — the speed and mood of a piece or a particular movement.

Tempo markings like Largo, Adagio, Allegro, and Presto appear frequently in titles or movement descriptions. These help performers understand the pacing and character intended by the composer.

Sometimes, additional modifiers are included:

Con anima (with spirit),

Agitato (restless or agitated),

A piacere (at the performer’s discretion).

An example of these modifiers used in a title would be Symphony No. 5 in E Minor, Op. 64: I. Andante – Allegro con anima by Tchaikovsky.

This tells us that the piece is a symphony, the fifth he wrote, in the key of E minor, cataloged as his 64th opus. The first movement moves from a walking tempo (andante) to a livelier, more spirited pace (allegro con anima).

Here are some other examples of tempo terms and their approximate beats per minute (bpm):

Largo (40–60 bpm)

Lento (45–60 bpm)

Adagio (66–76 bpm)

Andante (76–108 bpm)

Allegro (120–156 bpm)

Vivace (156–176 bpm)

Presto (168–200 bpm)

Each of these tempo indicators serves to guide consistent performance and contribute to the personality of each movement.

Movements

Large-scale compositions — especially symphonies and concertos — are usually divided into movements. These are distinct sections with their own themes, tempo, and form.

Movements are often labeled with Roman numerals and tempo instructions. For example, Vivaldi’s "The Four Seasons" includes four concertos, each with three movements. The "Spring" concerto is structured as follows:

Concerto No. 1 in E Major, Op. 8, RV 269, 'Spring':

I. Allegro (in E Major)

II. Largo e pianissimo sempre (in C-sharp Minor)

III. Allegro pastorale (in E Major)

Each movement stands as a complete idea, but also contributes to the larger work. On recordings or streaming platforms, movements are often presented as separate tracks. So since The Four Seasons consists of four concertos with three movements each, Spotify lists out twelve “tracks” in total.

You won’t see these broken down any further — movements are the smallest meaningful unit in classical structure.

Stepping into the World of Music

At first glance, classical titles may look complex. But once you understand the system — form, instrumentation, key, opus or catalog number, tempo, and movement — it becomes much easier to navigate.

You don’t need to memorize it all. But now, when you come across a piece like Symphony No. 9 in D Minor, Op. 125 'Choral', you’ll understand what each part of the title means, and why it matters.

Now, happy listening!

Remember, you can support us and get members-only content every week: great literature, art, and philosophy breakdowns.

Paid readers can access our *entire* archive of premium articles right here.

This Saturday, paid readers will receive our ultimate beginner’s guide to classical music. We break down the main eras of western art music, the best pieces from each era, and give you all the tools and guidance you need to start listening right away…

Thanks. Good reference file to give to others and to fall back on when trying to explain to others.

Forwarding to my piano students!