Is This What Hell Looks Like?

Bosch's Garden of Earthly Delights

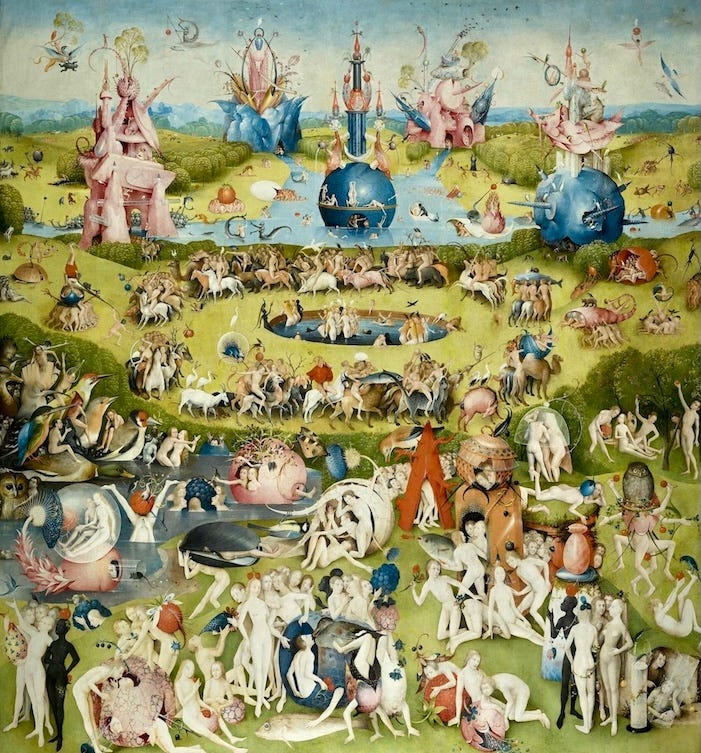

Hieronymus Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights is one of the most disturbing, yet simultaneously intriguing, paintings ever created.

More than just a feast for the eyes, it’s a work that bridges the gap between medieval and modern art — and is accordingly just as strange as you’d expect. But more than that, it’s a painting that asks provocative questions about the nature of beauty, horror, and hell.

Today, we explore one of the most famous works of the past millennium, and its 500-year-old warning…

Reminder: you can support our mission and get tons of members-only content for a few dollars per month:

Full-length articles every Wednesday and Saturday

Members-only podcasts and exclusive interviews

The entire archive of great literature, art, and philosophy breakdowns

In the last year, we’ve written about everything from Milton’s Paradise Lost, to why Tolkien hated Dune, to Dante’s tips for reading the Bible (or any epic story)…

A Mystery From a Mystery

Hieronymus Bosch is a historical enigma. The early Dutch Renaissance master left few details about his life, no personal writings, and no hints about what motivated his darkly fantastical paintings. The Garden of Earthly Delights, unquestionably his most famous work, is even more enigmatic than its artist.

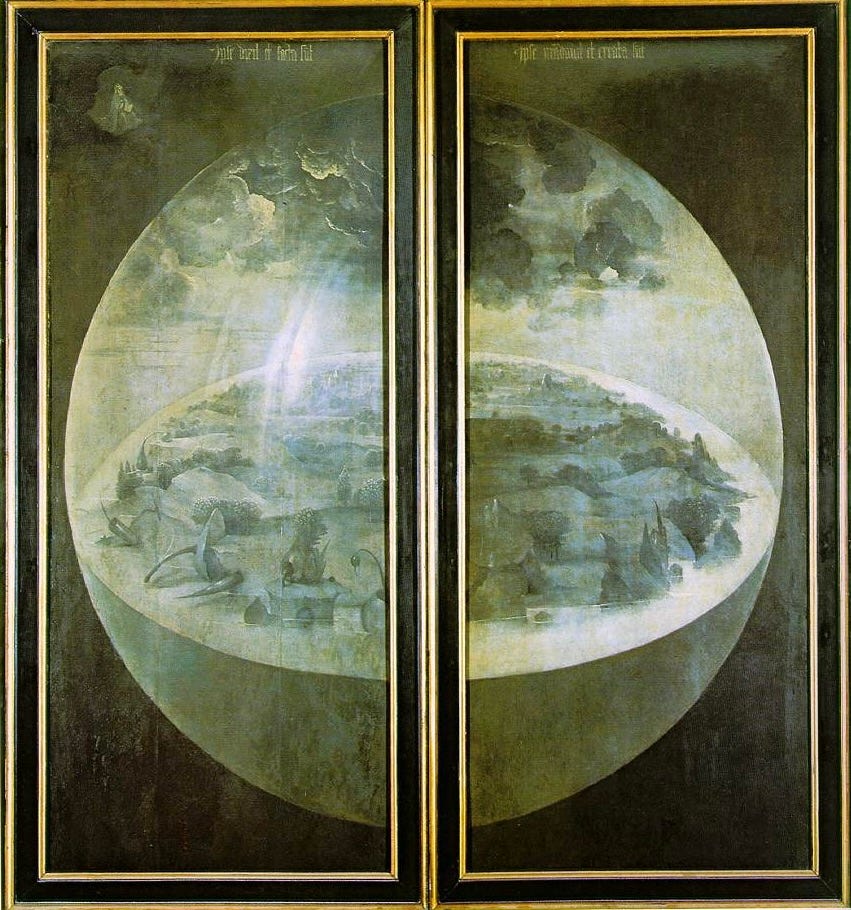

As a triptych — a three-panel painting that folds like a book — altarpiece, Bosch designed his Garden to be a vision of the whole world. To make this clear, he began by adorning the outside of the triptych with a globe that shows the third day of creation.

Once opened, the piece reads like a book from left to right. On the left panel, Adam and Eve meet for the first time in the Garden of Eden. In the center, innumerable human figures cavort in the Garden of Earthly Delights. And on the right, the story ends with tortured souls enduring agony in Hell.

But if this sounds like a straightforwardly moralistic painting, think again. Though the panels look like something from a nightmare-inducing hallucination, each one offers its own perspective and wisdom to the viewer…

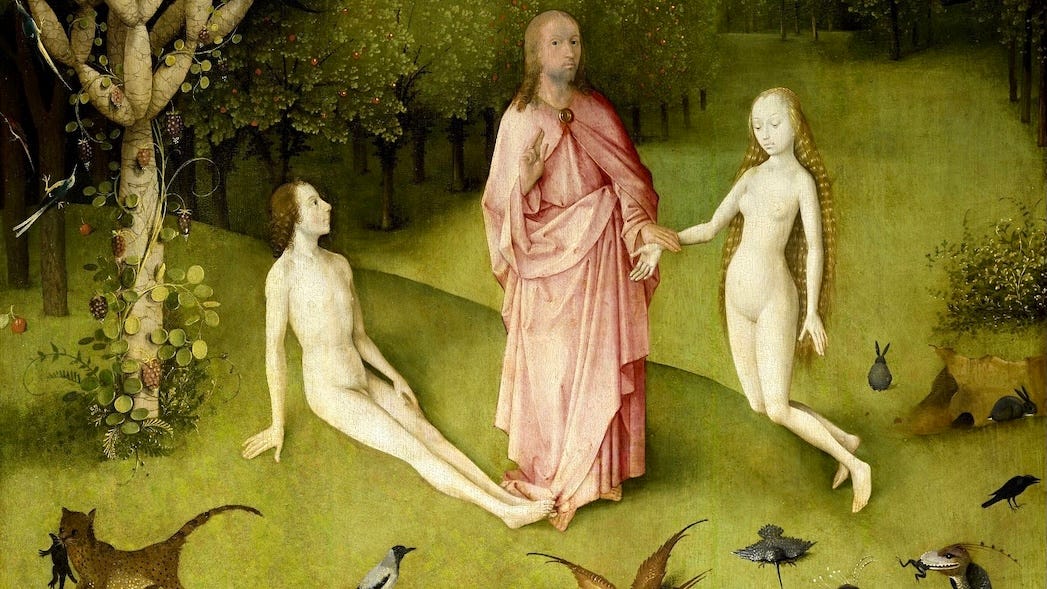

The Garden of Eden

You might think a painting about humanity’s descent into hedonism would begin with Eve taking her fateful bite of the forbidden fruit. But here, Bosch takes a deceptively peaceful direction.

The first panel depicts Adam in the Garden of Eden as God presents him with the first woman, Eve. The background scenery seems peaceful as a plethora of animals — especially those associated with fertility — roam about an idyllic landscape. The theme is romantic love, blessed by God.

However, there are some disturbing foreshadows of what’s to come. A three-headed lizard crawls out of the main pond, hinting at the presence of the Serpent. A pink statue appears to take the form of a sinister face — perhaps a surrealist depiction of Satan.

Even Adam’s rosy cheeks are a sign of trouble ahead, as blushing was considered a sign of arousal and lust. Man’s sinful nature will come to fruition in the next panel, but for now, all seems to be perfect.

But that’s the point: because even in the midst of what seems like paradise, evil is still lurking for a chance to strike…

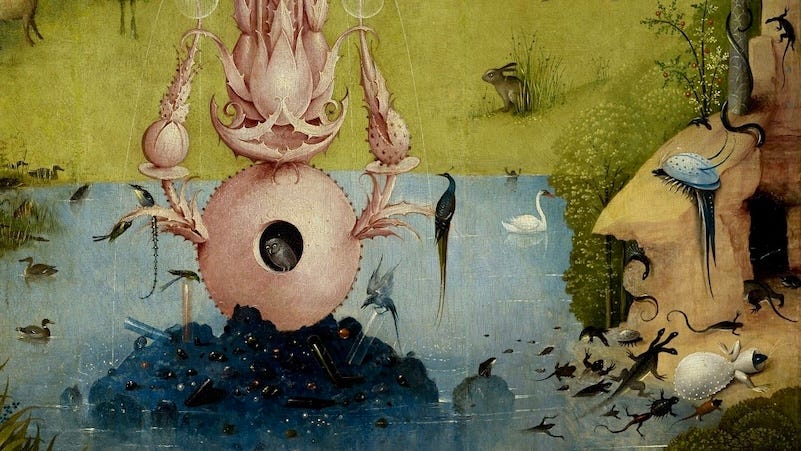

The Garden of Earthly Delights

The central panel explodes with nude figures. It’s a chaotic realm of animals, people, and plants that all intertwine in bizarre, disturbing ways. Particularly discerning viewers will notice the figure of God is no longer present.

Since this panel is also set in a garden, it’s easy to mistake it for a continuation of Eden — but Bosch is manipulating your confusion to make a point. Because while the Garden of Eden signifies paradise in the Bible, gardens in medieval art were often used to represent lovers and illicit sexuality. Bosch capitalizes on these two meanings to reveal just how easy it is to mistake earthly pleasures for heavenly joy.

A multitude of sexual symbols — from fruit to flowers to animals — abound, with some taking on particularly bizarre manifestations. Some figures are trapped inside water bubbles caressing delicious fruits. One places a bouquet between another’s buttocks. Still others chase each other while riding on the backs of various animals. And that just scratches the surface of their imaginative antics.

This panel has the feeling of walking into a crowded arcade: with so many enticements vying for your attention, you’re easily bewildered and don’t know where to look.

The imagery is almost all sexual, but it’s shorthand for all the types of gratification human beings chase. Bosch’s vision leaves you sickened at the obscene indulgence of lust, gluttony, and every other human appetite — yet at the same time, it’s hard to look away…

Hell

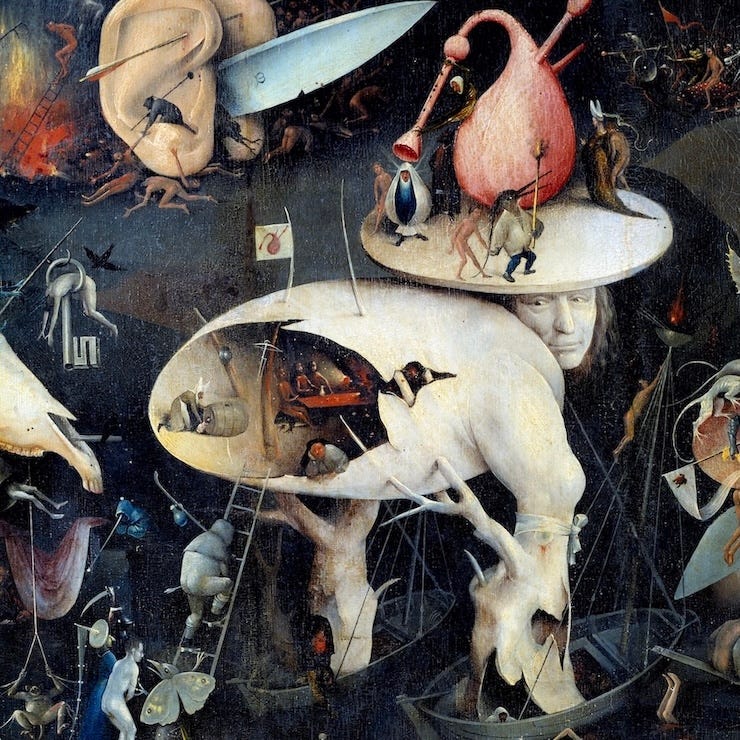

The final panel of Bosch’s triptych shows the artist’s vision of where unbridled self-indulgence leads — to a hell unlike any you’ve seen before.

Instead of devils with pitchforks, everyday items like musical instruments become instruments of torture. Horrifying monsters operate nameless, mechanical torture devices, and some of the damned are crushed under a gigantic pair of ears.

It’s a scene of terror that defies description, and its horror rests largely on the fact that normal objects have been nightmarishly perverted to become the focal points of hell.

Yet this surrealist world of torture is not entirely bereft of logic, as some of the damned suffer torments that fit their earthly sins. For example, a glutton is forced to vomit into a pit, and a vain woman stares at her reflection while devilish hands grab at her.

It’s precisely because Bosch leaves out the standard symbols of hellish punishment that his realm of the damned is so horrifying — it’s as if damnation means that logic itself begins to dissolve into insanity.

The final major theme of note in Bosch’s Hell is that all the horror is man-made: the organic-looking structures of previous panels are gone, and everything is now decidedly industrial. All the creations of man, even the musical instruments, have turned on him…

What Does It All Mean?

The strangest thing about this painting, however, is when it was made. It wasn’t created in the 20th century, nor during an era of absurdism or nihilism. Rather, it was painted within years of Da Vinci’s Last Supper — i.e., during the height of the Renaissance.

The Garden of Earthly Delights clearly trespasses the Renaissance’s core theme of humanism. Instead of celebrating man’s potential, Bosch displays the downward spiral that humanity’s undisciplined passions create. But that’s not to say that Bosch was a rule-bound moralist.

Yes, religious paintings were the accepted genre of his time, but Garden was unlike any moral artwork yet seen. Its sheer weirdness and horror clearly set it apart. The key to understanding the painting, though, is to realize that it’s not actually as much a departure from traditional Christian art as it first seems.

Scholarly opinion has never fully settled whether Bosch was a fervent Christian believer or an intentional critic of organized religion. But perhaps he was something else entirely — a thinker whom the artistic norms of his day couldn’t contain, and who presented the nightmares of his imagination with an ironic relationship to his faith.

The Gargoyles that Guard

Lastly, The Garden of Earthly Delights takes its inspiration in large part from medieval gargoyles. These grotesque figures traditionally perched on the outer walls of churches, adding a counterpoint of ugliness and disorder to an otherwise immaculately designed cathedral. They were lewd, confusing, and downright disturbing — exactly like Garden.

Medieval art used gargoyles to make a statement: if you don’t live your life in harmony with the beauty and order that built the great cathedrals, you’ll fall into a life of ugliness and chaos. Likewise, the horrors of The Garden of Earthly Delights serve a similarly indispensable purpose: they clear your vision so you can see the ugliness of self-gratification.

The final panel of Bosch’s masterpiece is rendered in such horrifying detail that only a true visionary could imagine. Its purpose, however, isn’t mere shock value — because hidden below the veneer of abject terror is a deeper moral lesson, one that might inspire you to choose another direction for your life before it’s too late…

Thank you for reading!

Remember, you can support us and get members-only content every weekend — great literature, art, and philosophy breakdowns.

Paid readers can access our *entire* archive of premium articles right here.

In the last year, we’ve written about everything from Milton’s Paradise Lost, to why Tolkien hated Dune, to Dante’s tips for reading the Bible (or any epic story)…

Masterpiece. Thanks for the analysis. On my bucket list to see it at the Museo del Prado in Madrid.

Bosch was truly ahead of his time. I love spending time with works like this because it reminds us that people back then were not so different to how they are now. The peculiarities, jokes, quirks and mischief in paintings like Bosch's remind us that these artists, though they lived hundreds of years ago, were still amused by similar things to us. I wonder through all the centuries, how many people have stood in front of this triptych and had a giggle, or recoiled, or just been straight up confused.