Short Classics You Can Read in a Weekend

Essential reads under 200 pages

Not all classic works of literature take months to read. While there’s much to love about the drawn-out, slow burn experience of wading through The Count of Monte Cristo or The Lord of the Rings, there’s just as much to love about the classics you can read in a single weekend.

Such books are unique because their brevity augments the power of their message rather than weakening it. The fact that they resonate with you so profoundly after just a few sittings is testament to both the author’s skill and the truth of what they have to say.

Today, we look at five classics you can read in a weekend. If you’re tight on time but still want to fuel your mind with great literature, there are few books better than these to start with…

Reminder: you can support us and get tons of members-only content for a few dollars per month. You’ll get:

New, full-length articles 2x per week

The entire archive of content (150+ articles, essays, and podcasts)

Membership to our bi-weekly book club (and community of lifelong learners)

We are currently reading Dostoevsky’s “Notes from Underground” in our subscriber book club. We are meeting TODAY, November 5th, at noon ET — please join us!

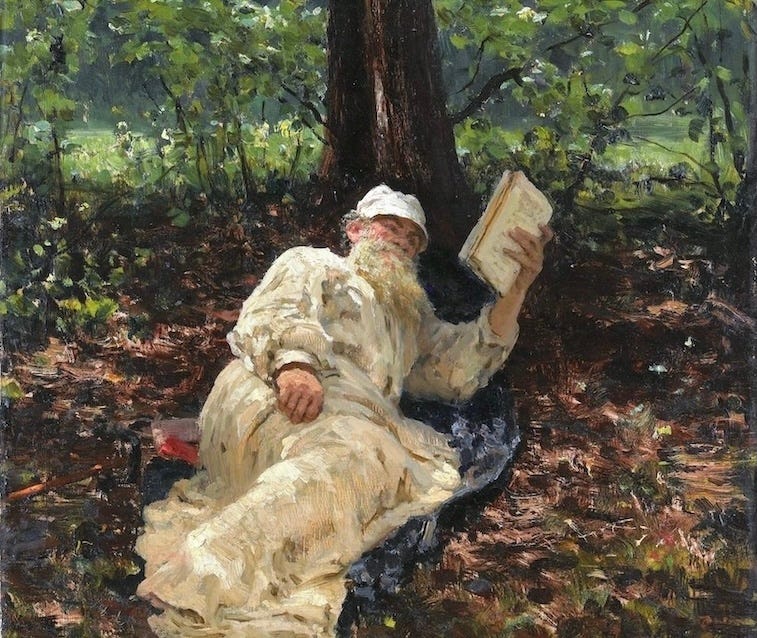

1) The Death of Ivan Ilyich by Leo Tolstoy

Tolstoy’s The Death of Ivan Ilyich (1886) is among the most profound meditations on mortality ever written. The story follows a high-ranking judge whose comfortable, respectable life quickly unravels when he becomes terminally ill.

As Ivan faces death, he begins to see how hollow his existence has been, and how it was defined by social propriety and career success rather than truth or love. Over the course of about 90 pages, Tolstoy strips away every illusion of modern life until only the essential question remains: how should one live?

Few works so succinctly capture the terror of confronting the reality of one’s death. But, in the words of Tolstoy, “In place of death there was light” — a metaphor for the transcendence that occurs when you come to peace with your mortality…

2) The Metamorphosis by Franz Kafka

Published in 1915, The Metamorphosis begins with one of the most arresting opening lines in all of literature:

When Gregor Samsa woke up one morning from unsettling dreams, he found himself changed in his bed into a monstrous vermin.

From this absurd premise, Kafka builds a haunting allegory of alienation and guilt. Gregor’s grotesque transformation into a literal insect exposes the fragility of human dignity, and how quickly family affection can dissolve into horror and disgust when usefulness disappears.

Yet despite its overt strangeness, the story is more complex than it seems: it can be read as a metaphor of a man trapped in heartbreaking circumstances, or — if you don’t trust the narrator in the opening line — as a story about a man who becomes the victim of his own decay. Interpretations are aplenty, but one thing is certain: you won’t be bored reading it.

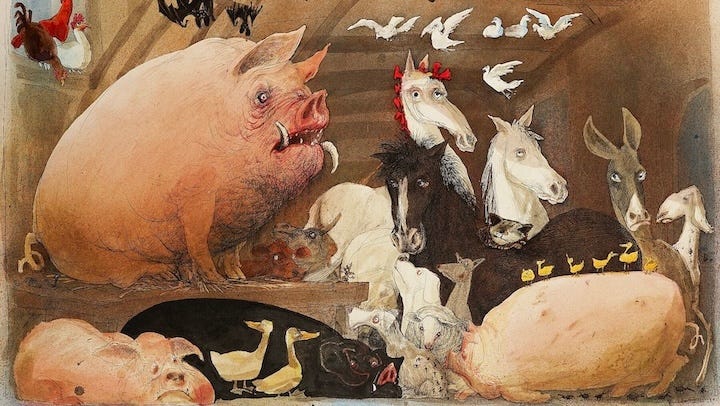

3) Animal Farm by George Orwell

Orwell’s 1945 novella is often remembered as a political allegory about Soviet totalitarianism. Its staying power, however, lies in just how easily its satirical lessons extend beyond its specific, mid-20th century context.

When the animals of Manor Farm overthrow their human masters, they dream of equality and freedom. But instead they build a new tyranny, ruled by pigs who twist language and truth to their advantage. In less than 120 pages, Orwell captures the entire cycle (and spirit) of political revolution: from hope to corruption, and corruption to betrayal.

Every generation finds something new in Animal Farm, because power always finds new disguises. Who could have thought that a story about politically-savvy pigs would have so much staying power?

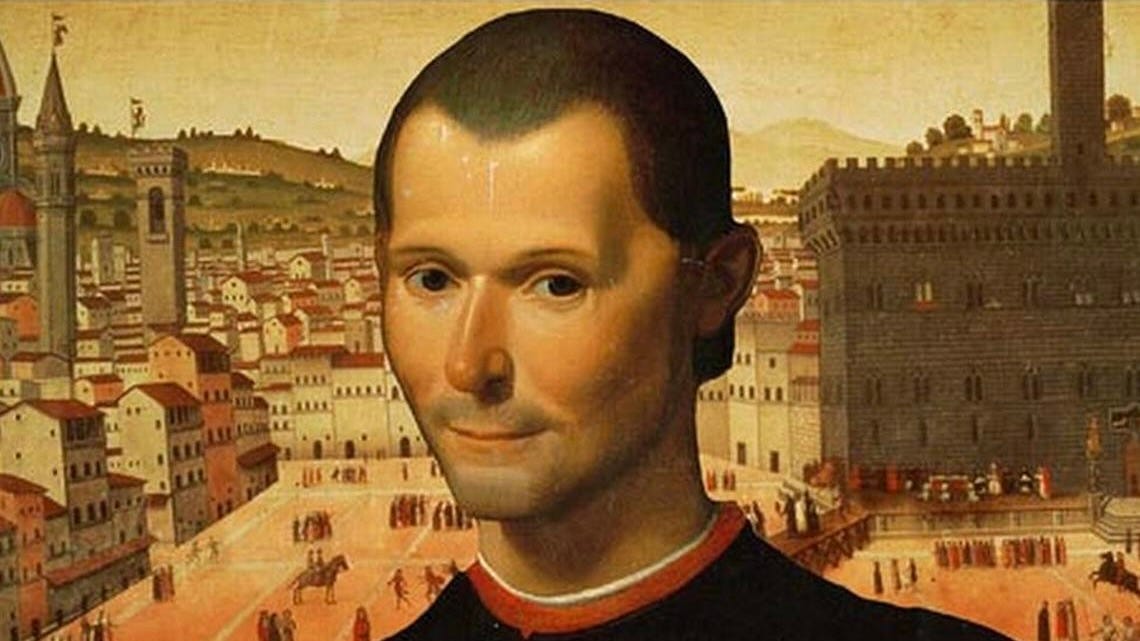

4) The Prince by Niccolò Machiavelli

Written in 1513, The Prince remains one of the most influential — and misunderstood — political treatises in history.

Far from advocating cruelty for its own sake, Machiavelli sought to describe politics as it truly is, not as we wish it to be. He wrote for rulers who must act in a world of deceit, ambition, and shifting fortune.

Or did he? As we pointed out in a previous article, multiple interpretations of Machiavelli exist. Everyone from Nietzsche to Hegel saw something in his work that resonated with them; an essential truth about political power and the moral cost of wielding it.

Coming in at just over 100 pages, there’s no excuse why you can’t read The Prince to find out for yourself what it’s really about. Or, in the words of the Machiavelli himself:

“The wise does at once what the fool does at last.”

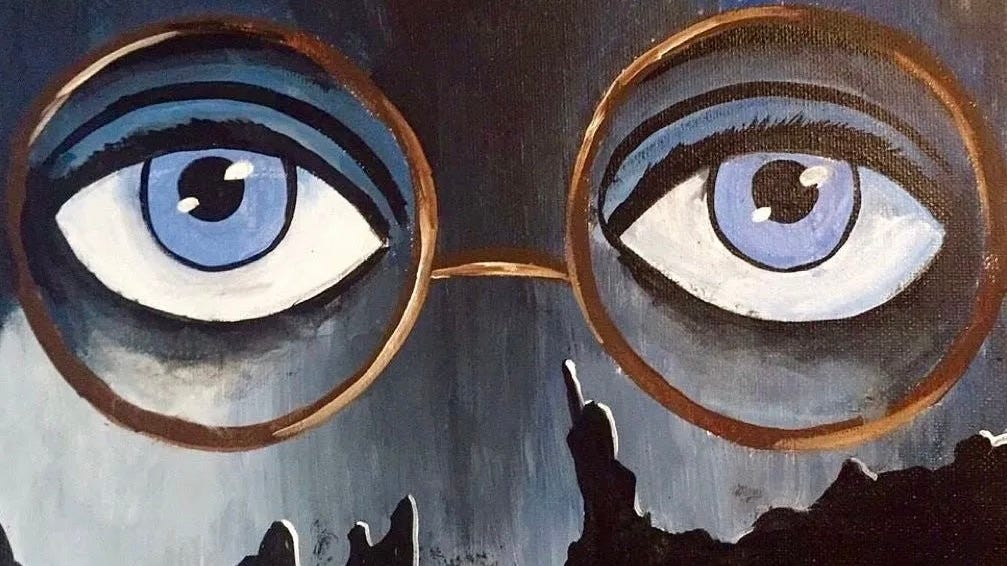

5) The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald

At 180 pages, 1925’s The Great Gatsby is the longest of the books on this list. Yet given that it’s both a tragic love story and a critique of the American Dream, few novels capture so much in so few words.

Gatsby’s world is one of excess, where men are either weak or reckless, women are lost in their own illusions, and the pursuit of pleasure drowns out meaning. In many ways, it’s a prophecy about our own roaring 20s, as well as a damning condemnation of them.

Throughout it all, Fitzgerald’s prose shimmers like the perlage of a fine champagne, yet the tale he spins leaves you feeling like the morning after the party. The Great Gatsby is glamorous, decadent, and disastrous: a perfect allusion to much of our world today…

Happy reading!

Reminder that we are currently reading Dostoevsky’s timeless novella, Notes from Underground, in our subscriber book club.

Notes is itself a prophetic work on the dangers of rationalism and utopianism, but it is also useful to be read as an introduction to Dostoevsky’s later (and much longer) novels.

This is the last call for the session happening Wednesday, November 5th, at noon Eastern Time. If you can’t make it, we will also post the recording to Substack for book club members.

If you would like to join in, please take out a premium subscription to our publication, and then jump inside our chat room for announcements, links to the sessions, and general discussion.

On the surface, The Metamorphosis reads like a nightmare about alienation.

Gregor Samsa wakes up one morning as a giant insect and slowly loses the love of his family. But symbolically, it’s saying a lot more than that.

Gregor’s transformation just makes visible what was already true: he was valued for his usefulness, not for who he was. The bug form is a picture of modern life, where people get dehumanized, turned into parts of a machine, reduced to what they can produce. In that sense, Kafka’s story is almost apocalyptic: the veil lifts, and we see the spiritual reality of the modern “machine world.”

There’s also a haunting twist on the Incarnation here. Instead of God becoming man to heal creation, man becomes beast to carry the weight of a world that’s cut itself off from grace.

It’s a haunting read.

Great list! Thanks for sharing 🙏