How to See the World as Enchanted Again

C.S. Lewis' 4 ages of life

One of the strangest features of modern life is that we inhabit a world overflowing with beauty and mystery, yet often experience it as though it were drained of meaning.

To many, maturity means having a flattened and disenchanted vision of reality.

But C.S. Lewis believed this assumption is profoundly mistaken, and that real maturity is actually what allows you to see the world with eyes of enchantment. What many call “disillusion” or “disenchantment” isn’t the result of discovering that the world lacks wonder, but of training yourself out of the ability to perceive it.

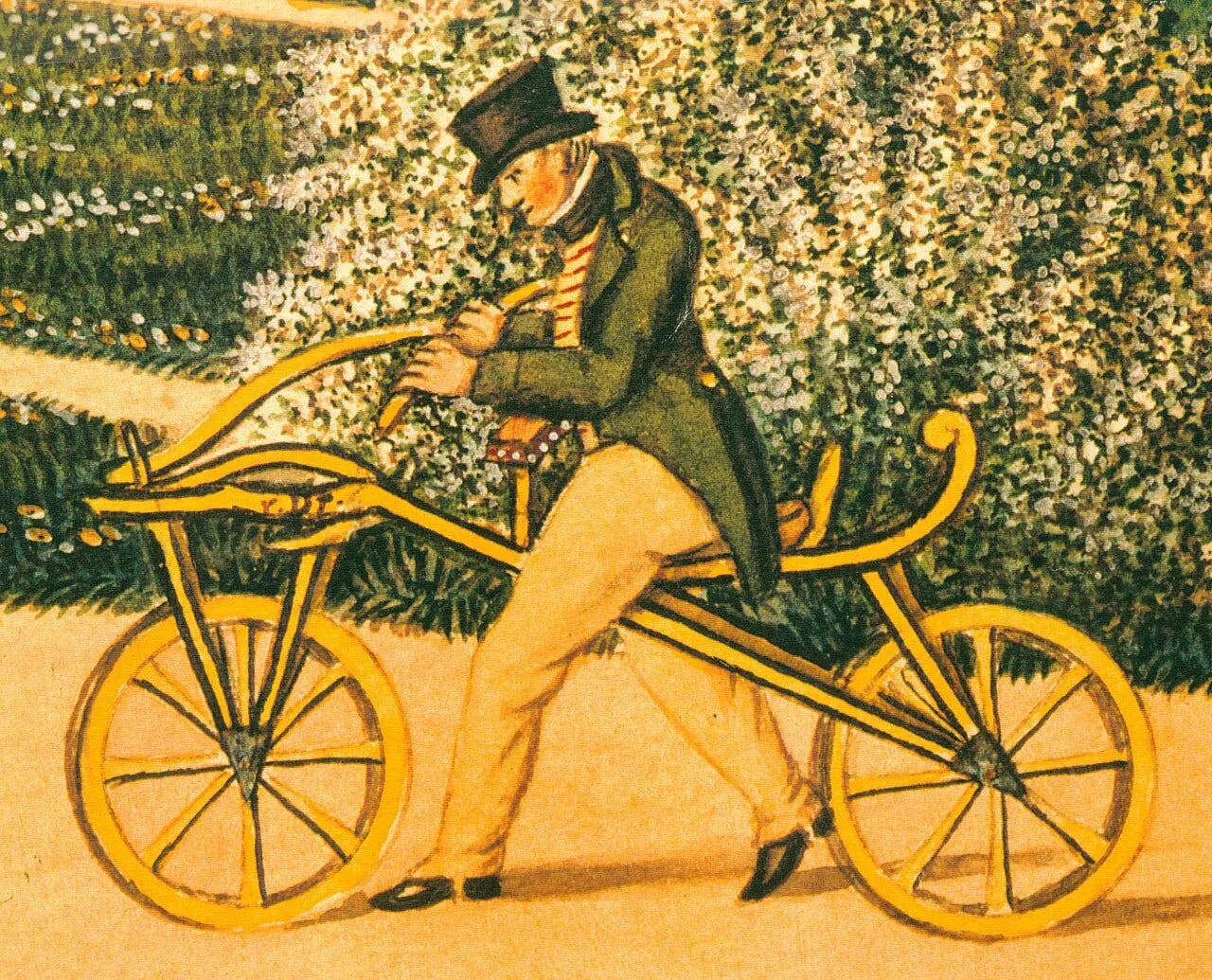

To illustrate this, Lewis gives the example of the bicycle. By showing how he relates to it in four distinct phases of life, he reveals the key to viewing both life and love through the lens of permanent enchantment...

Reminder: we are a reader-supported publication. This newsletter is free, but if you’re able to support us, please consider a premium subscription. You’ll get:

Full-length articles 2x per week

The entire archive of content (180+ articles, essays, and podcasts)

Our book club is about to start C.S. Lewis’s Screwtape Letters. The first discussion is TODAY, February 11, at noon ET. Join us!

The Four Ages

In the first of the four ages, the bike is entirely invisible to young Lewis as something that carries any meaning. At this point, he has experienced nothing, so his “un-enchantment” has no depth to it.

I can remember a time in early childhood when a bicycle meant nothing to me: it was just part of the huge, meaningless background of grown-up gadgets against which life went on.

In the second age, Lewis discovers the bicycle for the first time with a deep sense of joy and wonder.

Then came a time when to have a bicycle, and to have learned to ride it, and to be at last spinning along on one’s own, early in the morning, under trees, in and out of the shadows, was like entering Paradise. That apparently effortless and frictionless gliding—more like swimming than any other motion, but really most like the discovery of a fifth element—that seemed to have solved the secret of life. Now one would begin to be happy.

The enchantment of the bicycle, however, cannot last forever. With time, it becomes overly familiar, and the difficulties of riding it become apparent.

But, of course, I soon reached the third period. Pedalling to and fro from school (it was one of those journeys that feel up-hill both ways) in all weathers, soon revealed the prose of cycling. The bicycle, itself, became to me what his oar is to a galley slave.

Be careful to note that this state of dis-enchantment is distinct from the earlier un-enchantment. The world is full of un-enchanted people who mistake themselves for dis-enchanted. The dis-enchanted man, having already stepped through wonder, has a very different task ahead of him.

When Lewis goes back to riding his bike to work in adulthood, his perspective shifts again.

But again and again the mere fact of riding brings back a delicious whiff of memory. I recover the feelings of the second age. What’s more, I see how true they were—how philosophical, even. For it really is a remarkably pleasant motion. To be sure, it is not a recipe for happiness as I then thought. In that sense the second age was a mirage. But a mirage of something. . . . Whether there is, or whether there is not, in this world or in any other, the kind of happiness which one’s first experiences of cycling seemed to promise, still, on any view, it is something to have had the idea of it. The value of the thing promised remains even if that particular promise was false—even if all possible promises of it are false.

The first impression of the bike was something of a “mirage.” It promised a kind of joy that could never last. But this experience was something in and of itself, because the mirage was pointing at something true.

By way of example, Lewis describes a donkey with a carrot in front of its nose. The donkey may enjoy the smell of the carrot more than actually eating it would later please him. But as an old donkey, he would be happier to have smelt it, than not to have known the smell at all…

Otherwise I might still have thought eating was the greatest happiness. Now I know there’s something far better—the something that came to me in the smell of the carrot.

Love as a Way of Seeing

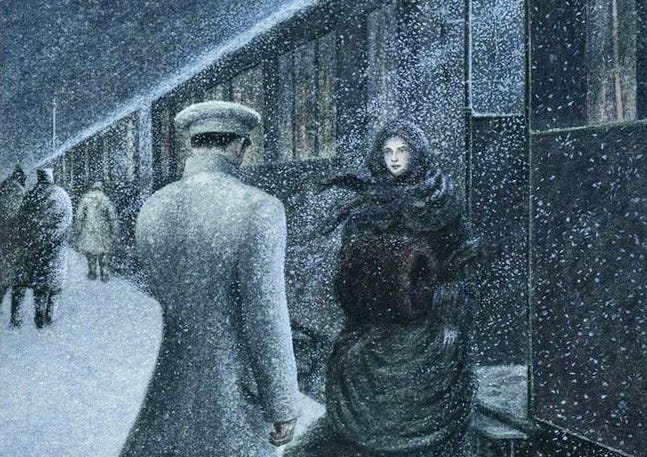

Falling in love for the first time is a kind of enchantment, destined to grow stale in the dis-enchanted state. But then, just as with the bicycle, true love is nurtured through experience. It’s about being able to see the earlier infatuation state for the “mirage” that it is.

You must be acutely aware that it was a mirage that you cannot replicate, but know that it was pointing at something even greater: a deeper love that is arrived at through experience. The fact that you felt the infatuation so fiercely, but were able to lose it, means that you were searching for something even greater. And without having felt the infatuation, you would never have known. Now, in hindsight, from it flow “things the boy and girl could never have dreamed of.”

In Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, we read:

“I always loved you, and if one loves anyone, one loves the whole person, just as they are and not as one would like them to be.”

True love is re-enchantment, reached consciously and with experience — a way of seeing with hindsight, and extracting from past experience what was most true.

It is to know the whole thing, not just its ideal parts. Once you know the whole truth, meditating on the mirage brings it back into being more fully than ever before.

Pay the Price

Re-enchantment in a more general sense, then, is looking at the world with this kind of mature understanding. It has nothing to do with pretending the world is magical when it is not. Instead, it’s an encounter with what you already know well, with a new appreciation for the wonder with which you initially saw it.

To get to re-enchantment, you have to pay the price of experience first. For example, to write a work of such staggering depth and beauty as Homer’s war poetry first requires an experience that is not easy to bear:

You see in every line that the poet knows, quite as well as any modern, the horrible thing he is writing about. He celebrates heroism but he has paid the proper price for doing so. He sees the horror and yet sees also the glory.

In other words, don’t be discouraged by dis-enchantment. It’s what you must go through before you can establish a deep and lasting relationship with the world.

Dis-enchantment is paying the price for having seen the world with unbridled wonder. But now, finally, you can engage the world on even richer terms than were first presented to you.

Thank you for reading!

Reminder: we are about to start reading The Screwtape Letters together in our book club. The first, intro discussion is TODAY, February 11, noon ET (will be recorded if you can’t make it). The second session will be two weeks from now.

If you want to become a member of our book club and join all the discussions with us, you just need to take out a subscription to our publication for a few dollars per month — see you inside very soon!

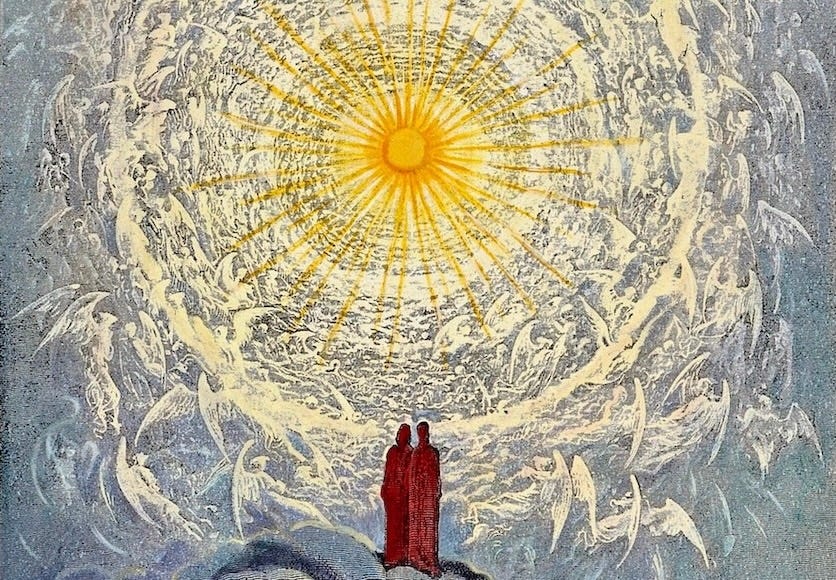

Also, you might be interested to know about our sister publication, The Ascent.

There, we are diving deeper into theology, mysticism, and ancient texts — please join us if that interests you! You’ll get one free article every Tuesday, and longer essays like this every Friday for paid readers.

Recently, we’ve written about the hidden meaning that connects Lewis’s Narnia with Dante’s Inferno, a break down of why Dante’s Inferno treats lying as worse than murder, and the problem with great books programs…

In my middle age,

I am remembering that I can do things that dirt can’t do — if I put dirt on a bike, it stays motionless.

If I am on a bike — I can go to places that dirt can’t go, and think about things dirt can’t think about, and feel thins it can feel.

So, re-enchantment is always a new insight away.

And again, I learnt something new. The 4 Ages, I never saw them like this.