The 4 Types of Men

And how they shape stories

In 1990, Jungian psychologist Robert Moore and mythologist Douglas Gillette published a sociological framework designed to help modern men reconnect with mature forms of manhood.

In it, they proposed that four archetypes of masculine psychology — the Warrior, Magician, Lover, and King — are present to varying degrees in every man.

The authors explained that each of these four archetypes is found in cultures around the world, and is particularly evident in the heroes and villains of literature and myth. They represent distinct modes of being, but are not fixed ideals — each archetype is expressed on a spectrum, from mature expression to distorted shadow.

Moore and Gillette’s work, while originally intended to help men better understand themselves, is just as helpful for any writer who wants to better understand the male psyche.

So in today’s article, we explore the virtues and the pitfalls of each male archetype — and see how they continue to shape the way we tell stories and understand ourselves…

Reminder: you can support our mission and get tons of members-only content for a few dollars per month:

Full-length articles every Wednesday and Saturday

Members-only podcasts and exclusive interviews

The entire archive of great literature, art, and philosophy breakdowns

The Warrior

The Warrior archetype represents the man who lives with conviction and clarity. He is disciplined and courageous, giving his loyalty to a cause beyond himself. Training relentlessly to serve that cause well, he knows what must be done, and does it.

Maximus in Gladiator offers a clear image of the mature Warrior. Though he suffers immense personal loss, he continues to fight out of principle. He lives by duty, his violence is measured, and his strength serves something beyond himself.

But before the Warrior comes into full maturity, he risks getting derailed by one of his two “shadows”, either the sadist or the masochist. The Sadist Warrior is brutal for the sake of dominance, detached from feeling or conscience — think of Colonel Kurtz in Apocalypse Now, who begins as a brilliant commander but descends into cruelty after detaching himself from moral restraint.

The Masochist Warrior, on the other hand, is what you get when discipline collapses. It’s a man who follows blindly, welcomes punishment, or lashes out from a place of pain.

In order to step into the fullness of who he’s meant to be, a man who fits into the Warrior archetype must discipline himself and act with purpose. He must measure his strength not by how much violence he can unleash, but by how well he can direct it.

The Magician

The Magician archetype represents the man who is thoughtful, perceptive, and drawn to knowledge. He stands slightly aloof from the “main characters”, preferring instead to guide and offer wisdom to others.

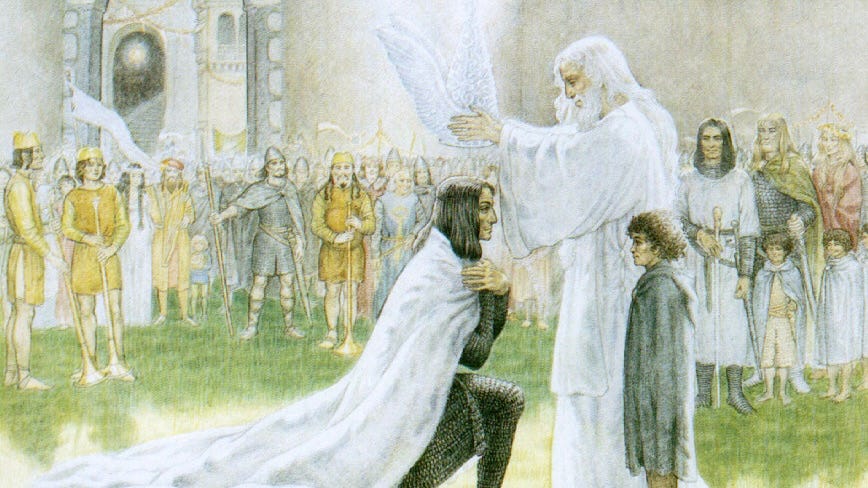

Gandalf in The Lord of the Rings embodies the Magician in full maturity. He knows more than he says, and speaks only when necessary. He withdraws when the time calls for reflection, only to reemerge with renewed insight and authority. His power lies primarily in wisdom — the wisdom of knowing when to act, and when to let others rise to the occasion.

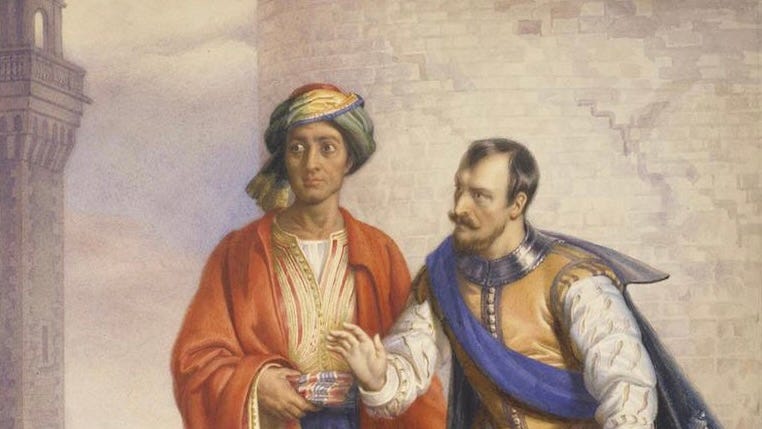

Just like the Warrior, however, the immature Magician risks warping into one of two shadow expressions: the manipulator or the withholder. Like Iago in Othello, who exploits trust to sow chaos while pretending to serve, the manipulator uses knowledge to deceive.

The withholder, on the other hand, retreats too far inward — like Dr. Frankenstein, he isolates himself in pursuit of knowledge, only to unleash consequences he refuses to take responsibility for.

To develop fully, the man who fits into the Magician archetype must not only seek the truth, but accept the burden that comes with knowing it. His knowledge must never be divorced from conscience, or else he risks becoming like Tolkien’s Saruman…

The Lover

The Lover archetype represents the man who is emotionally alive. He longs for connection with people, with beauty, and with life itself. He is, for both better and worse, driven more by his heart than his head.

A great example of the Lover comes in the form of Shakespeare’s Romeo. The young Montague experiences the world with heightened emotion — he is passionate and vulnerable, and sees opportunity in the face of all odds. His joie de vivre is contagious, and enables him to easily sweep young Juliet off her feet.

Yet because the Lover feels everything so strongly, he is especially vulnerable to excess and collapse. Romeo himself shows the risk — in the grip of overwhelming emotion, he acts rashly and takes his own life before he can pause to understand the truth. This is the Addicted Lover, so overtaken by emotion that he loses all sense of proportion.

The Impotent Lover, by contrast, shuts down entirely once things no longer go his way — Jay Gatsby after Daisy’s rejection shows this other extreme. Cut off from real connection, he fixates on a fantasy, and is ultimately paralyzed by disillusionment.

To grow into maturity, the healthy Lover must remain open without being consumed. His emotional depth is a strength, but only when guided by wisdom, restraint, and a sense of what is actually worthy of devotion.

The King

The King is the culmination of the previous three archetypes. When a man expresses the strength of the Warrior, the insight of the Magician, and the emotional vitality of the Lover — and does so with maturity — he becomes capable of embodying the King.

We see the mature King archetype in figures like Aragorn in The Lord of the Rings. Aragorn first proves himself a Warrior in countless battles, from leading the defense of Helm’s Deep to fighting in the last stand at the Black Gate. Then as a Lover, his commitment to Arwen shapes his choices long before he claims any throne — he carries the banner she made for him into battle, and refuses Éowyn’s affections out of loyalty. Finally, as a Magician he uses athelas to tend to the wounded in the Houses of Healing, thus fulfilling the prophecy that “the hands of the king are the hands of a healer.”

In all of this, Aragorn acts without self-assertion or ambition, the foremost example of the healthy King. Yet this archetype, too, has its shadows.

The Tyrant King, like Macbeth, is obsessed with control — he rules through fear, demands loyalty without earning it, and lashes out at anything that threatens his image. The Weakling King, on the other hand, avoids responsibility altogether. Like Hamlet’s uncle Claudius, he schemes from the shadows, unable to act decisively or inspire real loyalty.

Just like the greatest kings of old, the man who embodies the fullness of the King archetype must learn to bear the weight of power without being distorted by it. The good King recognizes that true leadership is selfless and sacrificial, and that he leads not for his own sake, but for the sake of those entrusted to him.

Brilliant article and I'm familiar with Jungian analysis and shadow work, but regarding these archetypes are they not too restricting? Though useful in character creation for creative fiction do they not fall short of the reality?

Whenever confronted with a limiting archetypal model, it begs the question 'Why only these personas?' Take the female tripartite goddess model of "Mother, Maiden, Crone", would any woman accept that they can ONLY fit into these classifications? Are women so restricted to these roles that are based on child bearing and the inability thereof? Likewise, are men so simple as to be either violent, sagely, amorous or controlling? Do not the seven ages of Man as portrayed in Shakespeare's As You Like It more apty define male gender roles?

Furthermore, I have issue with the King archetype as being the epitome of a "complete man" and can such a man ever exist? A kingly man is an amalgamation of the other three archetypes. If you succeed in incorporating them all and then slip due to some form of hubris and lose an element of an archetype are you no longer kingly? The shadow of the king are surely all of the shadows of the three other archetypes.

The king itself represents control. It is inherent to kingliness, to be authoritarian even if justified. But can a man only be complete if he is in full control? Is there not something to be learned in knowing you have no control?

I have no answers, only thoughts and questions. Perhaps more depth and variety could be found in character creation by instead considering The Tarot as archetypes? Consider the man as Hermit, as Fool, Priest, Death etc.

Again good article! It raises many questions.

Love this. Clear, concise, and insightful. Thank you