Is Life Really Meaningless?

The Bible's most perplexing book

In a perfect world, the comforting sayings of the Bible’s Book of Proverbs are always true: the diligent prosper, the wise are exalted, and the wicked are brought low.

But of course, we don’t live in a perfect world. At times, it even seems like the promises made in Proverbs couldn’t be farther from life’s reality. Hard work and wisdom don’t guarantee success, the wicked get away with their crimes, and the prideful prosper.

So what are we to make of this discrepancy?

This is precisely the question at the heart of the Book of Ecclesiastes, a book that accuses God of creating a world in which all our efforts are in vain. It rebuts the wisdom of Proverbs, and makes you wrestle with the futility, or “meaninglessness”, of life. But most shockingly, it never fully resolves the questions it poses, and there’s no textbook “happy ending” to Ecclesiastes.

So what are we supposed to make of such a perplexing book, and why has such a depressing bit of Scripture nonetheless managed to inspire millions?

That’s exactly what we look at today…

Reminder: this is a teaser of our members-only deep dives.

To support our mission and get exclusive content every single week, upgrade for a few dollars per month. You’ll get:

Full-length articles 2x per week

The entire archive of premium articles and podcasts

Membership to our bi-weekly book club (+ subscriber chat room)

Our paid subscriber Great Books Club is currently reading Dostoevsky’s “Notes from Underground”. The next meeting is on Wednesday, November 5, noon ET — join us!

The Words of Qohelet

Ecclesiastes opens by introducing the man who will do most of the speaking during the book:

The words of Qohelet, the son of David, king in Jerusalem.

-Ecclesiastes 1:1

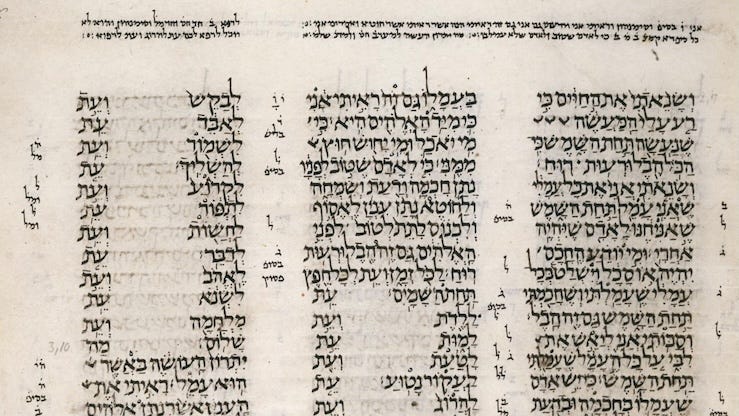

Already four words in, we’ve hit the first major mystery of Ecclesiastes: who is Qohelet? In Hebrew, the word קֹהֶלֶת isn’t a name at all, but rather a noun meaning “the one who gathers people”. The word is often translated as “the teacher” or “the preacher” because of this, going by the assumption that the people have been gathered together to learn.

But the mystery doesn’t stop there, as the descriptor “son of David, king in Jerusalem” is more vague than it first appears as well. While some people think it literally means David’s son King Solomon, others believe that it is Qohelet taking on the character of a “Solomonic king” — in other words, speaking as the fictionalized ideal of kingly wisdom in order to better undermine the concept of wisdom itself.

This latter perspective is supported by the presence of Persian loanwords in the Hebrew text, which leads scholars to believe Ecclesiastes was written during the post-Exilic period long after Solomon. Lines such as “I have acquired great wisdom, surpassing all who were over Jerusalem before me” also seem strange to say if you’re only the third king of Israel (and presumably a wise one!).

Either way, the point is this: Qohelet is not the author of Ecclesiastes, he is simply the man who is allowed to speak for the majority of it. This fact might seem insignificant in the beginning, but it is a crucial point — because at the end of Ecclesiastes, the true author of the book will return to offer an important commentary on Qohelet’s perspective…

Everything Is Hevel

Vanity of vanities, says the Preacher,

vanity of vanities! All is vanity.

What does man gain by all the toil

at which he toils under the sun?

-Ecclesiastes 1:2-3

Qohelet touches on many arguments, but his main one is this: every aspect of life, everything you see around you, is hevel. He uses the word no less than 38 times throughout the book, and it’s the key to understanding his message.

Many English Bibles translate hevel as “meaningless”, while others translate it as “vanity”, in the sense of being “in vain”. Yet neither of these fully capture the full sense of the word, which in Hebrew actually means “vapor” or “smoke”. In Ecclesiastes, it’s used to paint the picture that all of life is temporary or fleeting, just like smoke from a campfire or a thick, winter fog — it seems real while it’s in front of you, but the second you try to grasp it, it vanishes.

Even the smallest of winds can blow life’s beauty and goodness away from you at a moment’s notice. Qohelet phrases it as such:

I have seen everything that is done under the sun, and behold, all is hevel and a striving after wind.

-Ecclesiastes 1:14

He goes on to expand on a long list of things that are hevel: youth, beauty, hard work, wisdom, knowledge, wealth, and more. And to drive the point home even further, the entirety of his speech is bookended by the phrase hevel havalim — literally “breath of breaths”, but translated as “vanity of vanities”. Just like the “king of kings” or the “Lord of Lords”, it’s an intensifying phrase used to convey the supreme example of a thing. Qohelet both begins and ends his discourse with it, declaring “Hevel havalim! All is hevel.”

But how are you supposed to live when everything around you is hevel? If the entirety of your efforts are nothing more than a striving after wind, how should that impact how you live in the here and now?

What is the key to enjoying life under the sun?

Qohelet himself hints at a solution, but it’s not until the true author of Ecclesiastes speaks that you finally get the real answer…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Culturist to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.