The Hidden Meaning of Harry Potter

A surprisingly familiar tale

When the Harry Potter series rose to international fame in the early 2000s, there was one group who wasn’t particularly happy about it: Christians.

Some believers argued that Harry Potter mainstreamed practices of witchcraft, saying “the problem is not simply magic, but the way Rowling’s world presents occultism as something empowering and desirable for children.” Concerned that the books made occultism seem harmless, many evangelicals resolved to keep a safe distance from the franchise.

Yet at the same time, other believers rallied to the cause, arguing that Harry Potter was, in fact, a profoundly Christian work. Carrie Birmingham, for example, in her 2013 address Harry Potter and the Baptism of the Imagination, stated:

I believe that readers of the Harry Potter series experience imaginatively the essence of the Christian story, over and over, in the presence of traditional Christian patterns and symbols, Christian allegories, and even direct references to scripture. Millions of Harry Potter readers all over the world have received a baptism of the imagination, an imaginative and compelling introduction to the essence of the Gospel.

Indeed, much could be said about specific elements of Harry Potter that seem to be near-perfect Christian metaphors: from Harry’s death at King’s Cross to the character of Sirius Black, a man condemned to death for a crime he didn’t commit, and whose friends are named Peter, James, and John (Peter Pettigrew, James Potter, and Remus John Lupin, for you curious readers).

Today, however, we’re going to look at something else: instead of focusing on the detailed specifics of Christian imagery in Harry Potter, we’re going to examine the entire story zoomed out.

For it is in doing so that the Christian underpinnings of the series become impossible to ignore…

Reminder: this is a teaser of our members-only deep dives.

To support our work and get exclusive content every week, please consider upgrading for just a few dollars per month. You’ll get:

New, full-length articles 2x per week

The entire archive of content (150+ articles and podcasts)

Membership to our bi-weekly book club (and community of readers)

Our book club has just voted to read Beowulf, the foundational epic poem in the English language. The first (introductory) discussion is on December 17, at noon ET — don’t miss it!

A Familiar Story

Despite the over one million words that make up the seven books of Harry Potter, the main plot is simple: an unremarkable “chosen one” saves the world from evil through love and sacrifice.

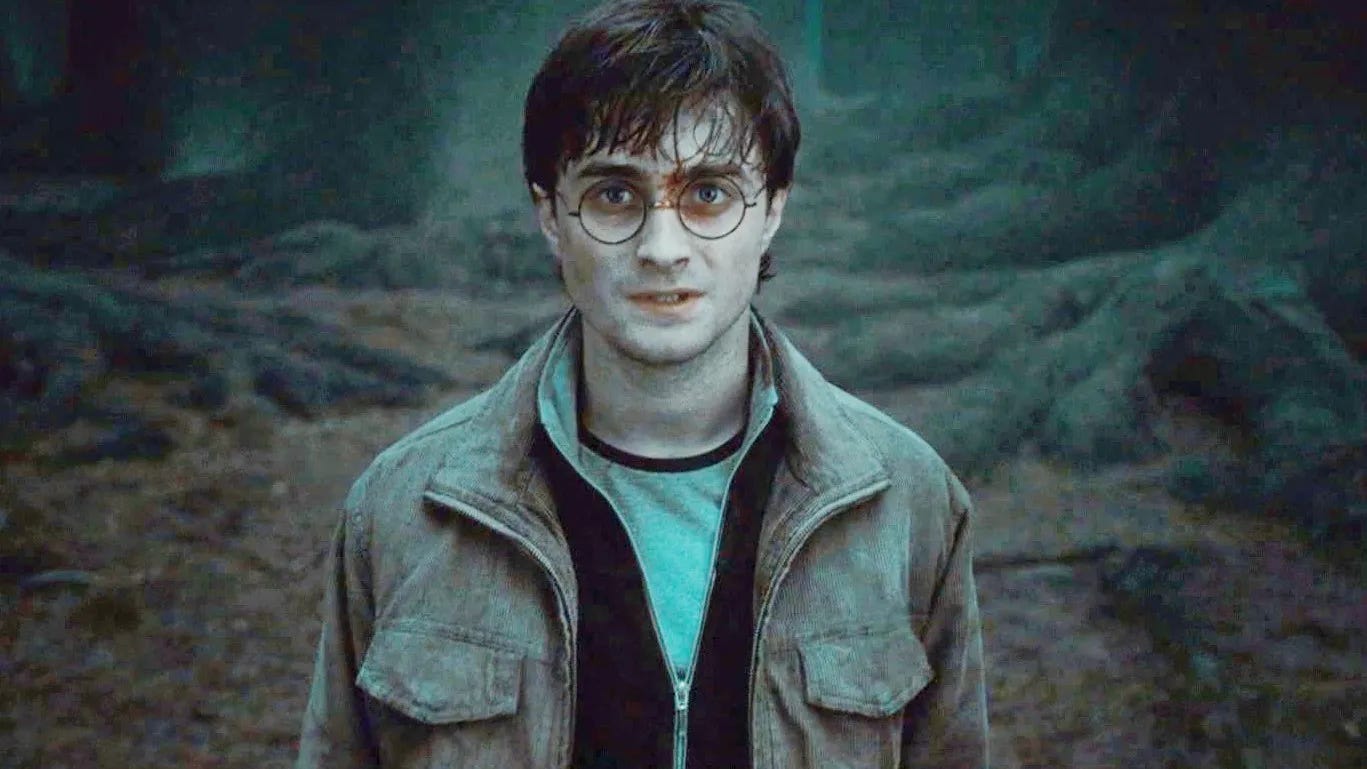

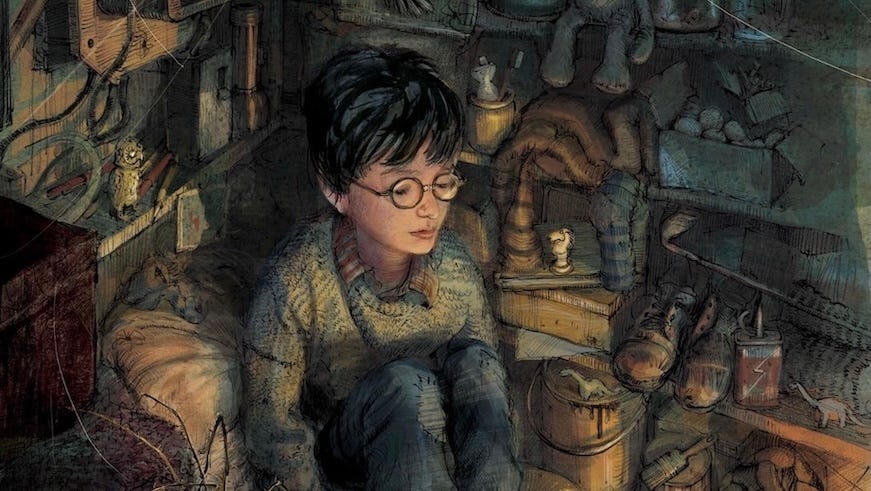

The parallels between Harry’s story and that of Jesus are many: Christ came from the forgotten backwater of Nazareth (“Can anything good come from there?”), and we first meet Harry in the cupboard under the stairs. Both characters die and resurrect from the dead to save the world, and even Harry’s moniker “the Chosen One” recalls the word Christ, “the anointed one”.

What’s more, in both stories humanity’s redemption begins with a parent’s decision to sacrifice her/Himself out of love for her child/His children, and Voldemort/death is only defeated after what first seems like a resounding victory for evil. From a bird’s-eye-view, there seems to be little difference between the story arcs of Harry and Christ.

Apart from the main characters, however, the broader world of Harry Potter also reflects Gospel themes of love, sacrifice, and redemption. Those who encounter this love are transformed because of their encounter with it: in this, Severus Snape is the example par excellence. His relationship with Lily reflects even the Catholic understanding of the Virgin Mary, namely that she takes wounded, conflicted souls and orients them toward the good they cannot yet see clearly.

Indeed, it is through his love for Lily that Snape comes to serve her son, and is himself redeemed…

He Who Has Eyes to See

One of the defining features of Harry Potter is that magic is real and active, but hidden. London, Diagon Alley, and Hogwarts all exist side by side with the ordinary world, yet only those with the right capacity can perceive them.

The structure of Rowling’s world thus establishes the premise that reality is larger than it appears, that there is a dimension to the world that most people never see, and that some forms of truth must be physically entered into. These premises reflect the Christian vision which proposes that, in addition to our material reality, there is also a spiritual dimension to our existence, one which most cannot (or choose not to) see.

Just as wizards live in the same physical world as muggles, so do believers live alongside the non-religious, yet they perceive and experience a different order of meaning, danger, beauty, and possibility. And while some muggles simply cannot see magic, others endeavor to actively suppress it. The Dursleys are the best example of this, as Vernon in particular works tirelessly to keep the “other world” out precisely because it undermines the narrow, controllable universe he prefers.

So far, these aspects of Harry Potter are confined to the story itself, and whether or not J. K. Rowling wrote them as intentional parallels to Christian belief is up for debate.

But still, there’s something surreal that she never could have planned, and which makes even the meta-narrative of the Harry Potter franchise reflect the Gospel story: that the creation would turn upon its creator, and try to have her crucified…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Culturist to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.