The Meaning of the Cross in Different Cultures

4 radically different ideas

With roughly 2.5 billion adherents, Christianity is the largest religion in the world. It is practiced all across the globe, from Australia to the Andes and even Antarctica.

Naturally, this diversity inevitably leads to different interpretations of the faith. Though the metaphorical “ingredients” of the Christian religion remain the same, the emphasis on each of them varies, resulting in different “flavors” of the faith in different parts of the world. Some focus on growing in personal virtue, others on cultivating a robust prayer life, others still on providing aid to the poor.

Nowhere is this cultural difference more pronounced, perhaps, than when looking at the defining symbol of Christianity: the Cross. What does it actually mean that Jesus died on the Cross? And what did his death accomplish?

If you ask those questions to Christians living in the United States and Christians living in China, you’re likely to get surprisingly different answers. Today, then, we explore four unique interpretations of the Cross, and what Christ’s death means in different parts of the world…

Thank you so much for reading this year! If you’d like to support our work, please consider taking out a paid subscription — it helps us out enormously. Plus, you’ll get:

New, full-length articles 2x per week

The entire archive of content (150+ articles and podcasts)

Membership to our bi-weekly book club (and community of readers)

Our book club has just voted to read Beowulf, the foundational epic poem in the English language. The first (introductory) discussion is on December 17, at noon ET — don’t miss it!

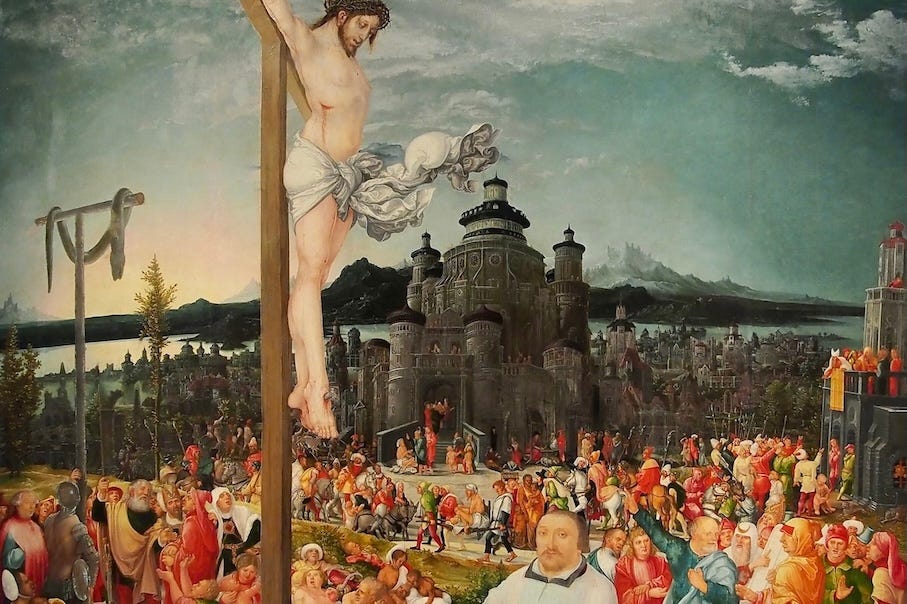

1. Western Christianity: Repayment of Debt

In the modern Western imagination, particularly in the United States and the broader English-speaking world, moral life is commonly framed in legal and financial terms. Responsibility is individual, and obligations are clearly defined. When something goes wrong, the central question becomes one of accountability: who is responsible for this?

Within this cultural framework, the Cross is often understood through the language of debt and repayment. Sin is experienced as guilt, a failure that demands satisfaction. Something has gone wrong, and the fault must be repaid.

In light of this understanding, Christ’s death on the Cross is interpreted as the substitutionary act that resolves a moral imbalance. The Cross becomes the place where humanity’s guilt is erased, and the debt it owes is paid in full.

To be clear, this language originates in the Bible, not the Anglosphere. In his letter to the Colossians, for example, the Apostle Paul writes the following:

And you, who were dead in your trespasses…God made alive together with him…by canceling the record of debt that stood against us with its legal demands.

-Colossians 2:13–14

Elsewhere, Paul frames Christ’s death as a substitution that satisfies justice, and which opens the door to man becoming just:

For our sake he made him to be sin who knew no sin, so that in him we might become the righteousness of God.

-2 Corinthians 5:21

In Western societies shaped by courts, contracts, and commerce, this language resonates deeply. On the Cross, Jesus repays debts and takes on the guilt of others so that justice can be satisfied. The Gospel is preached using economic and juridical terms, because these are the terms Westerners most readily understand.

But of course, things look a bit different in other parts of the world…

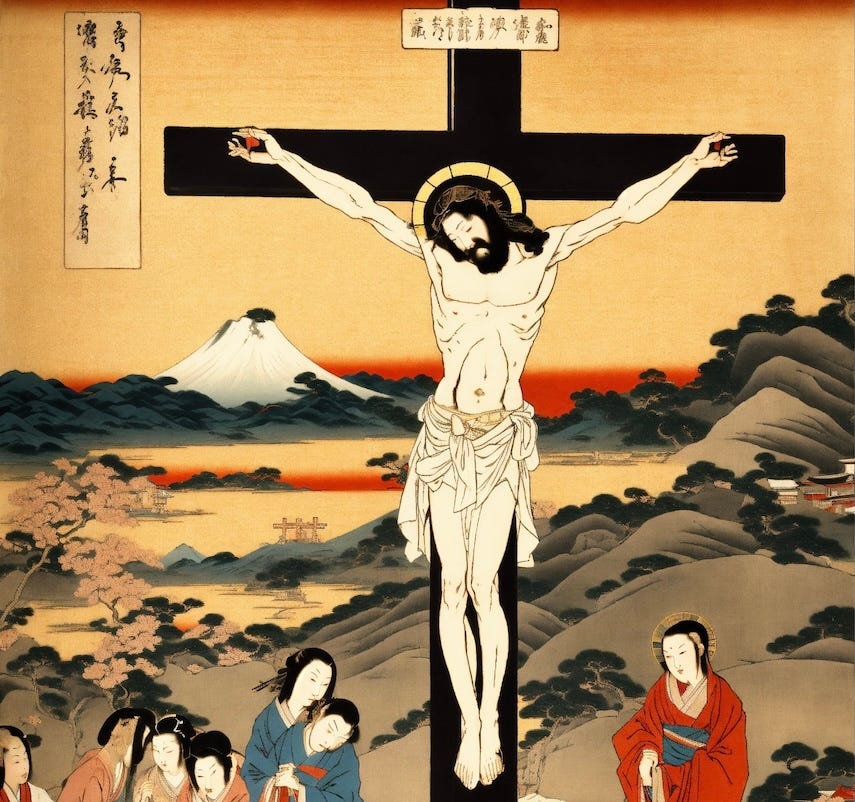

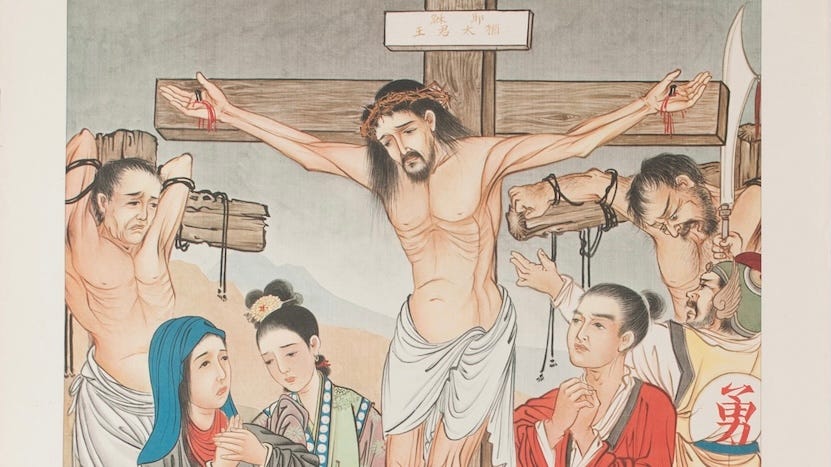

2. East Asia: Restoration of Honor

In many East Asian cultures, moral failure is not experienced primarily as legal guilt, but as shame. What is feared most is dishonor and the loss of standing within family and community. Since identity is relational, one’s actions reflect not only on oneself, but on those to whom one belongs.

In this world, the Cross is often interpreted as the place where Christ assumes humanity’s shame and restores its honor. The public nature of Jesus’s suffering becomes central. He is mocked, stripped, rejected, and executed outside the city walls, exposed before the world.

Once more, it is Scripture itself that emphasizes this dimension. The Letter to the Hebrews, for example, describes Christ’s death in explicitly shame-laden terms:

Looking to Jesus, the founder and perfecter of our faith, who for the joy that was set before him endured the Cross, despising the shame…

-Hebrews 12:2

The Old Testament Book of Isaiah (often referred to as the “fifth gospel”) also picks up on this same angle:

He was despised and rejected by men,

a man of sorrows and acquainted with grief;

and as one from whom men hide their faces

he was despised, and we esteemed him not.

-Isaiah 53:3

In East Asian cultures, redemption is often experienced as restored dignity. The Cross is seen as the moment when Christ publicly identifies with those who have lost their honor, so that their shame no longer defines them. He enters into humiliation willingly, so that:

“Whoever believes in him will not be put to shame”

-1 Peter 2:6

When shared in shame-based cultures, the Gospel message frequently emphasizes reconciliation, restored identity, and belonging. Through Christ’s sacrifice and humiliation, followers are raised to stand without fear, no longer marked by what once diminished them. As Saint Peter writes, the Cross makes it so that “the honor is for you who believe.”

So far, we’ve looked at how the focal points of the Gospel message differ in the West and the East. But what gets focused on in Russian culture, or in Africa?

And more importantly, what can all of these different perspectives teach you about the universal meaning of the Cross? That’s exactly what we look at next…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Culturist to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.