What Was Medieval University Like?

The 7 subjects they studied...

In today’s world, the phrase “liberal arts” is often associated with colleges and universities. Admissions directors use it to describe a course of study that comprises the humanities, social sciences, and an emphasis on critical thinking.

At best, it’s a vague and an uninspiring term — at worst, it’s a phrase that’s been overused to the point of meaning practically nothing.

But a brief glimpse at the etymology of “liberal arts” tells a radically different story. The artes liberales — or the “tools of freedom” — were the subjects that made you free to think for yourself and navigate the world around you. The original Latin, which is most accurately translated as “the disciplines (arts) of free men”, captures this vividly.

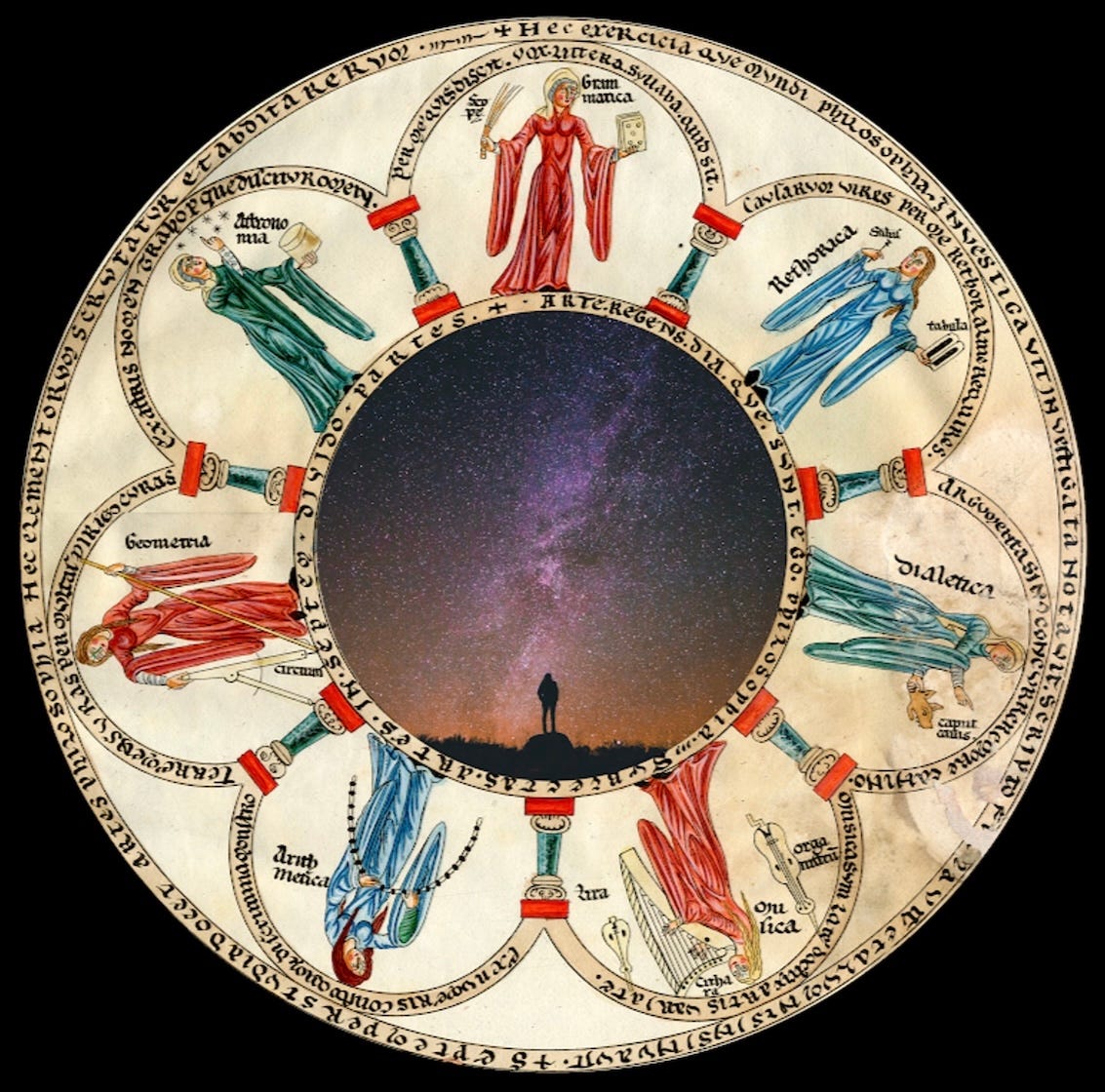

In the middle ages, these artes liberales were broken into seven main subjects within two larger groups. The first, the Trivium, comprised the “arts of language” (grammar, logic, and rhetoric). The second was called the Quadrivium and comprised the “arts of number” (arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy).

Today, we explore the inner workings of the trivium and quadrivium to better understand what students would have studied at a medieval university — and how it compares to what students are taught today…

Reminder: you can support our mission and get tons of members-only content for a few dollars per month:

Full-length articles every Wednesday and Saturday

Members-only podcasts and exclusive interviews

The entire archive of great literature, art, and philosophy breakdowns

Grammar

Grammar was the first subject in the trivium and the foundation of medieval education. It taught students how to read, write, and think with clarity through the mastery of Latin.

Medieval professors believed that grammar was the gateway to knowledge, and no serious learning could take place without it. As such, their students studied classical texts to master the mechanics of language — both in general terms, and specific to the language of Latin itself.

Since all serious fields of higher education were conducted in Latin, a robust training in grammar was absolutely mandatory before you could proceed to study other subjects.

Logic

After grammar, the second element of the trivium was logic. Building directly on the grammatical precision developed via grammar, logic trained students to critically evaluate ideas.

By using texts like Aristotle’s Organon and Boethius’s commentaries, students learned how to construct valid arguments and identify logical fallacies. Their main focus was on the structure of argumentation, such as which conclusions followed from which premises, and how the rationale behind different theories could be tested.

Disputations were a key part of the subject’s curriculum. In these formal debates, students had to defend or refute claims using precise logic. The training was rigorous, but it served an essential role in helping students prepare for advanced study in theology, law, or philosophy.

Rhetoric

The final subject in the trivium was rhetoric, the art of effective communication. Once students had learned to understand language through grammar and arguments through logic, they turned to rhetoric to be able to express those ideas with clarity and force.

By drawing on classical authors like Cicero and Quintilian, students learned how to craft persuasive speeches and win over their audience. As logic had already been covered, the goal with rhetoric was to convey that logic compellingly, in ways others could both enjoy and understand.

Because in a world where sermons shaped popular opinion and public speeches shaped policy, the mastery of rhetoric was an invaluable tool for young scholars to possess…

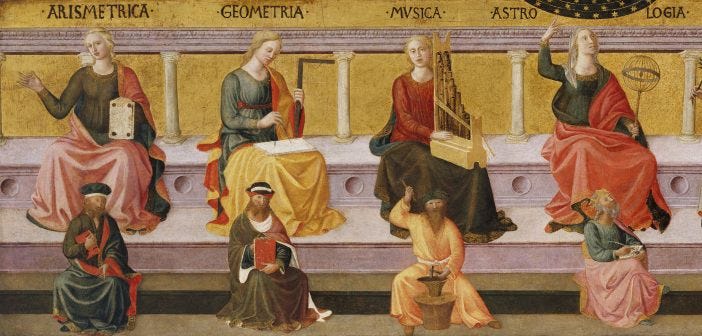

Arithmetic

Arithmetic was the first subject in the quadrivium (the “arts of number”) and dealt with the most basic division of quantity: absolute multitude. Through this discipline, students learned the nature of numbers and their different kinds.

Unlike modern mathematics, medieval arithmetic wasn’t so much about making calculations as it was about understanding what numbers actually are in themselves — odd and even, prime and composite, perfect and imperfect. Using texts like Boethius’s De Institutione Arithmetica, students explored how numbers relate to one another in proportion and pattern, as well as the role they play in intellectual and cosmic order.

Since numbers were thought to govern the structure of the cosmos, arithmetic was considered a foundational key to understanding reality itself. Indeed, it allowed its students to begin to perceive the hidden structure of creation…

Geometry

The second subject in the quadrivium was geometry, which dealt with quantity in space. While arithmetic studied numbers in the abstract, geometry applied those numbers to shapes, dimensions, and spatial relationships.

One of the field’s core texts was Euclid’s Elements, which trained students to reason deductively and build complex truths from simple axioms. If that sounds like something far beyond the scope of lines and angles, you’re right to think so — geometry was often considered a philosophical discipline, a reflection of divine order and proportion.

Whether used to construct buildings, chart the stars, or meditate on eternal truths, geometry taught students to see order in creation. Or as Hillsdale University’s Dr. Jeffrey Lehman put it:

“Plato saw the difference between the lower utility of using geometry to construct a temple and a higher utility of forming the soul.”

Music

The third subject in the quadrivium was music, but not in the modern sense of performance or composition. For medieval students, music was the study of numerical ratios in time.

Drawing on the works of Pythagoras and Boethius, students explored how different intervals and harmonies could be expressed mathematically. The focus was on proportion, or how sounds related to one another in ways that were both audible and measurable.

Music was seen as a bridge between the physical and the spiritual worlds. By studying it, students trained their ears and minds to recognize harmony both in sound and in the structure of the universe. Even today, the foundations laid by medieval scholars still continue to shape how music theory is studied in universities and conservatories across the globe.

Astronomy

The final subject in the quadrivium was astronomy, the study of numerical patterns in motion. It built on the principles of arithmetic, geometry, and music to track the movements of celestial bodies through time and space.

Students used Ptolemaic models to chart the paths of the sun, moon, planets, and stars. Through mathematical observation, they learned how to calculate eclipses, predict equinoxes, and understand the structure of the heavens.

Since medieval cosmology held that the heavens reflected divine order, astronomy was considered a deeply intellectual and theological discipline. It trained students to read the sky like a text, and played no small role in major artistic works like Dante’s Paradiso.

Thank you for reading!

Remember, you can support us and get members-only content every weekend — great literature, art, and philosophy breakdowns.

Paid readers can access our *entire* archive of premium articles right here.

In the last year, we’ve written about everything from Dante’s Divine Comedy, to the history of the Eternal City of Rome, to the coded messages in Leonardo da Vinci’s art…

I can't help but wonder if University needs to revert to this a bit 🤣

I certainly feel that grammar and logic should be applied this way in public schools here and now. Try to actually encourage people to be less like sheep.