Why Architecture Matters

What you build is who you are

“We shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us.”

Winston Churchill originally delivered this line in reference to the rebuilding of the House of Commons, which had been destroyed in a Nazi air raid in 1941. With it, he hoped to persuade Parliament to rebuild the bombed-out building exactly as it was — or in his words, to restore “its old form, convenience and dignity.”

His aphorism, however, has since taken on a life of its own, as it gets to a deep-rooted truth about architecture: the spaces we inhabit have a significant impact on us. Some buildings fill you with awe, while others depress you. But why is that?

The answer lies in the understanding that architecture is more than mere aesthetics. It’s the visible manifestation of a culture’s beliefs about humanity, meaning, and life itself…

Reminder: you can support us and get tons of members-only content for just a few dollars per month. You’ll get:

Full-length articles 2x per week

The entire archive of premium articles and podcasts

A Monument to Heaven

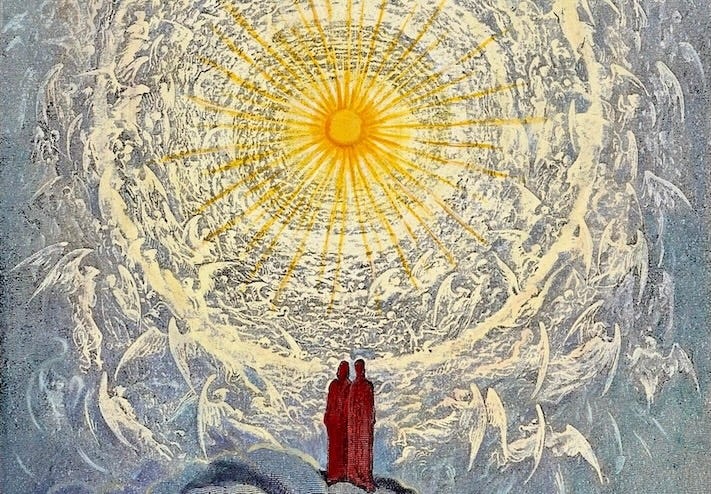

Staying in London, take the example of Westminster’s great Gothic church. Its pointed arches and lofty spires give the sense of upward movement. Its wide base adds a feeling of groundedness and solidity. Its fine embellishments like stained glass and carved arches suggest that even on the grandest of scales, no detail is too small to be overlooked.

This style of building emerged in Europe in the 12th and 13th centuries, and is a perfect reflection of the deepest beliefs of Europe in the late middle ages. Medieval architects took for granted that man’s purpose was to journey toward heaven, which is why they built a sense of upward motion into their cathedrals. Yet they also knew that in order to do so, you must stay grounded in your earthly life — and thus they gave their buildings a solid foundation, both functionally and visibly.

Most importantly, however, they believed that beauty has moral power. The designers wanted to create a building that would ennoble and inspire every person who walked in. They filled their churches with painstaking detail so that every aspect offered an encounter with the kind of beauty that draws man toward the divine.

But if the glory of medieval cathedrals was built on a conviction that we need to turn toward God, what about the churches of a very different time and place — for instance, 1970s America?

Rise of the Spaceship Churches

The late 20th century saw seismic shifts in America’s frame of reference. The world wars had come and gone, leaving a new hope for a conflict-free future. Space exploration promised to set humanity free from its last constraints. A new era of peace, built on advancements in science and technology, seemed ready to liberate man from his age-old struggles.

This science-fuelled optimism showed up in the media of the 60s and beyond. While real-life rockets raced to the moon, the Starship Enterprise spread its message of peace across the galaxy. Star Trek producer Gene Roddenberry believed in this brave new era so much that he boldly went where no producer had gone before: he told his writers to avoid any interpersonal conflict between the main characters.

Why? Because he was sure that humanity was on track to transcend petty problems like human conflict. By the 24th century, he believed, people wouldn’t have those kinds of problems. We were on track to save ourselves.

These humanist values showed up in the architecture of the time, too. Instead of spires that draw the eye up to Heaven, new flat roofs kept the focus here on earth. The extravagance of ornamentation vanished, replaced by blank walls — designers weren’t trying to ennoble anyone, perhaps because they believed man was already noble enough. Round buildings with amphitheater-style seating took the focus away from the altar where God and man meet, and instead emphasized the human community.

The message behind this architecture was clear: “We can solve our own problems — let’s focus on ourselves.” In other words, spaceship values build spaceship churches.

But what about our own cities in the modern day?

Modern-Day Cities

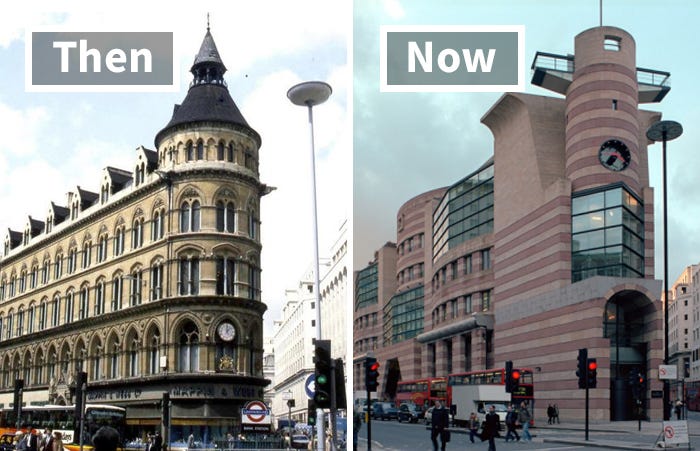

Whether a building’s designers are conscious of it or not, architecture always tells the story of a culture’s values. That’s why if you want to know what your culture believes today, you should look at what it builds.

The U.S., for example, is notorious for building automotive cities — cities that optimize for car traffic instead of human interaction. 3 out of 4 Americans drive to work, and there are over 200,000 drive-thrus across the country (restaurants, coffee shops, even banks). Unquestionably, the motorcar is a vehicle — literally and figuratively — of American freedom, and one of the greatest drivers of wealth in history. But what do cities designed around automobiles mean for the values of modern American culture?

Perhaps they suggest that efficiency is more important than beauty, or that convenience is more important than connection. Either way, it’s a productivity-based mindset that symbolizes a departure from the values that built the old world.

Take Prague, for example, considered by many to be one of the most enchanting cities in the world. In its more than 1,000 years of history, it has accumulated hundreds of church spires and historic buildings. It is small, dense, and walkable, with pedestrian-friendly bridges and cobblestone streets. Its main attractions aren’t shopping centers or fast-food outlets, but gardens, churches, and monuments.

When you walk through it today, you’re able to glimpse the values of the culture that built it: a culture that prioritized beauty, prayer, connection to the past, and staying connected to one’s community.

In an age that claims all beauty is in the eye of the beholder, it’s worth reminding ourselves that architecture is never neutral. In fact, it is arguably the best physical embodiment of what a culture believes and how it lives. It is shaped first by our values, and then reinforces those same values in us.

Next time you go out, be sure to take a close look at your house, your church, your pub, your city. Try to read the values that underlie the physical building. What do you see?

And perhaps more importantly, what would you like to see instead?

Thanks for reading!

P.S. Don’t forget to join our new sister publication, The Ascent.

The Ascent is our new space to dive deeper into theology, mysticism, and ancient texts. We study the ideas, history, and revolutionary teachings from 2,000 years of the Christian imagination, and how they can help the modern reader (religious or not) ascend upward.

One free article every Tuesday, and longer deep dives every Friday for paid readers…

I really enjoyed this read. It’ll make me look at architecture in my area differently. I appreciate the insight, Thank you!

Thank you for this article and all of your work. It truly is a delight. On the theme of architecture, I would recommend Roger Scruton's writings on the topic, in particular Building to Last in Confessions of a Heretic:

"[T]he real meaning of the modernist forms is that there is no God, that meaning has fled from the world, and that Big Brother is now in charge...A city is a constantly evolving fabric, patched and repaired for our changing uses, in which order emerges from an 'invisible hand' from the desire of peopel to get on with their neighbours. That is what products a city like Venice or Paris, where even the great monuments...soothe the eye and radiate a sense of belonging."