Why Myths Matter

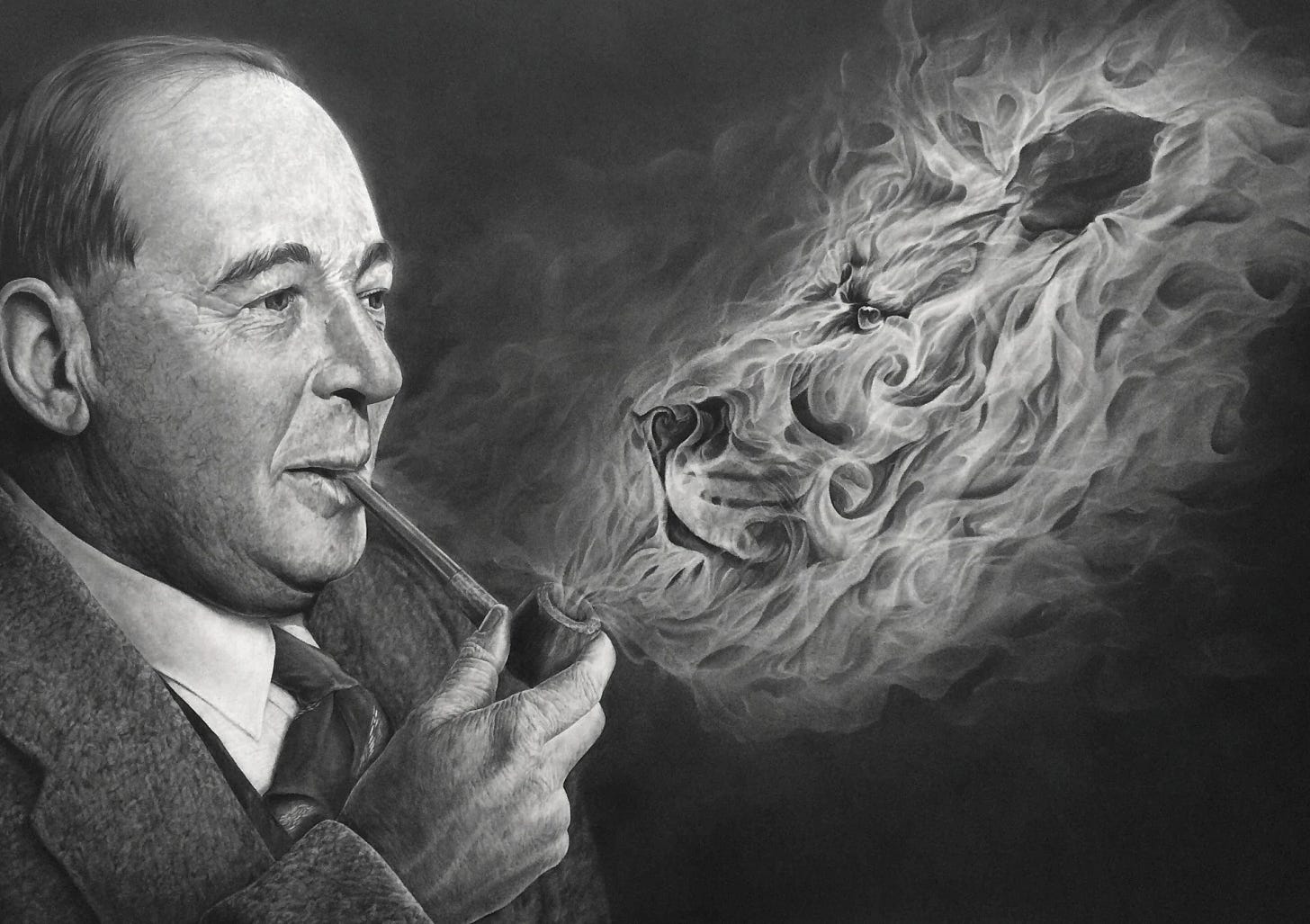

C.S. Lewis & the power of myth

C.S. Lewis was an author, scholar, and theologian — but above all, he was a man who cared deeply about myth. At a time when intellectual seriousness often meant rejecting the world of fantasy, Lewis was an outspoken advocate of mythic stories and their ability to convey meaning that rational explanations cannot fully express.

Lewis lived in a century shaped by scientific materialism, where the role of the imagination was sidelined. But despite this — or perhaps, because of it — he came to see imagination as a fundamental component of wisdom and understanding.

He believed that without myth, the modern mind becomes starved of wonder, morality, and hope.

His belief came from his own personal experience. As a child, Lewis had been stirred by stories and legends in ways that traditional religion could never match. It was only when he came to see Christianity as the fulfillment of the ancient stories he loved that he finally resolved a tension that had lived in him for years.

Today, we explore C.S. Lewis’ ideas about the power of myth. We first look at his personal experience, and then his beliefs about mythic stories themselves — why children need them, why adults need them, and how they convey otherwise indescribable eternal truths…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Culturist to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.