Why Read the Classics?

3 arguments why we must

What we call the new ideas are generally broken fragments of the old ideas.

-G.K. Chesterton

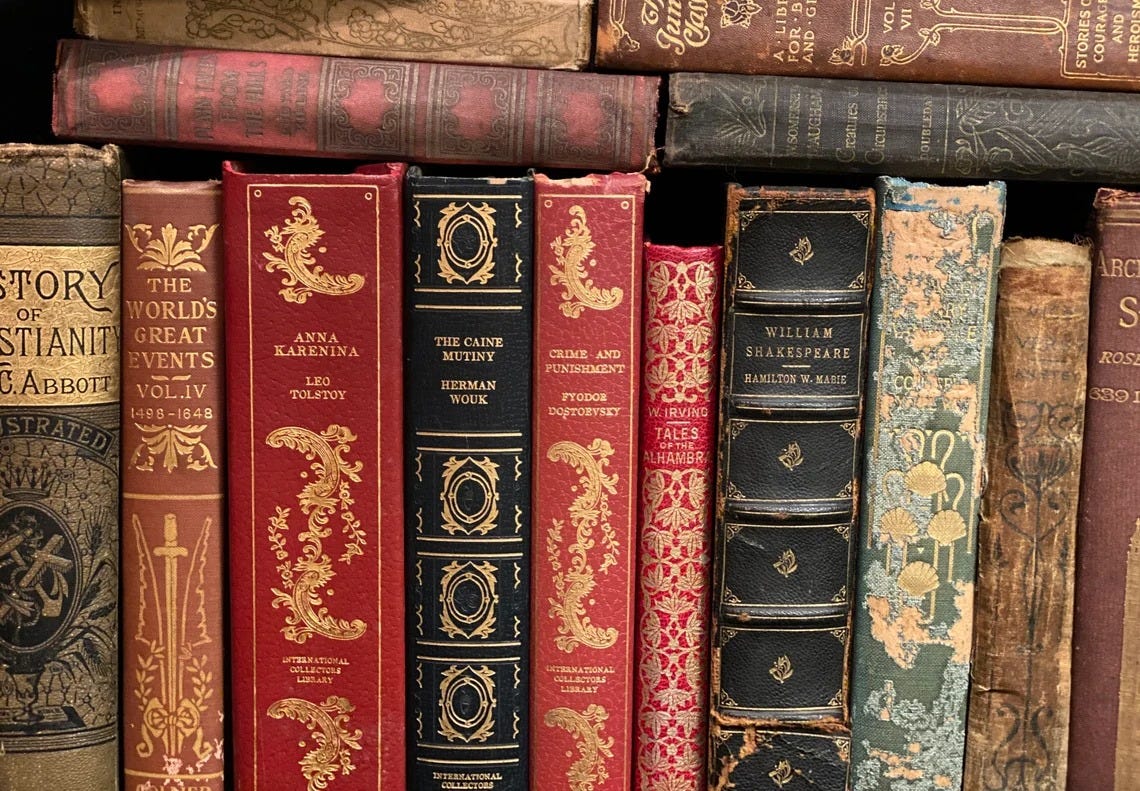

Classic literature is making a comeback like never before. The desire to read the Great Books has fueled an exodus from the public school system, with parents opting to either homeschool their children or send them to schools that follow a classical curriculum. Social media feeds are filled with exhortations to “read the classics!”, and movements like “dark academia” glorify the aesthetics of scholarship and old books.

But amidst all this enthusiasm, few people stop to genuinely ask why you should read the classics. The answer, it seems, is so self-evident that to question it at all would be to betray your ignorance. Yet it is a question worth asking, and indeed it has been asked by some of the greatest thinkers of the past century.

Among them is G.K. Chesterton, a British author and philosopher who penned the essay “On Reading” in response to this very question. In it, he refutes the ideas of writers like George Bernard Shaw and Friedrich Nietzsche, and outlines his reasons why you ought to read the classics.

Today, we explore his three main arguments to discover why the classics are indeed worth reading…

1) To Avoid Being “Merely Modern”

Chesterton begins his essay with the following:

The highest use of the great masters of literature is not literary; it is apart from their superb style and even from their emotional inspiration. The first use of good literature is that it prevents a man from being merely modern.

These opening lines set the tone for everything that’s to come: great literature, Chesterton argues, transcends the realm of literature itself and overflows into other areas of life. One of the first benefits of this, he says, is that it lifts you out of the myopic and mundane aspects of modern life.

But what does it mean to be “merely modern”? Chesterton continues:

To be merely modern is to condemn oneself to an ultimate narrowness; just as to spend one’s last earthly money on the newest hat is to condemn oneself to the old-fashioned. The road of the ancient centuries is strewn with dead moderns.

Literature, classic and enduring literature, does its best work in reminding us perpetually of the whole round of truth and balancing other and older ideas against the ideas to which we might for a moment be prone…

In other words, reading classic literature helps you expose yourself to the “full picture” of truth, not just the popular ideas or slivers of truth that dominate culture at the given moment. This allows you to avoid being a product of your time, and instead live informed by the wisdom of the ages.

2) To See Through Half-Truths

Chesterton continues by demonstrating why modern errors stem not from things that are wholly untrue, but rather dangerous half-truths:

From time to time in human history, but especially in restless epochs like our own, a certain class of things appears. In the old world they were called heresies. In the modern world they are called fads. Sometimes they are for a time useful; sometimes they are wholly mischievous. But they always consist of undue concentration upon some one truth or half-truth.

Thus it is true to insist upon God’s knowledge, but heretical to insist on it as Calvin did at the expense of his Love; thus it is true to desire a simple life, but heretical to desire it at the expense of good feeling and good manners…

Classic literature, Chesterton argues, inoculates you from these dangerous half-truths by exposing you to “the whole truth which humanity has found”. That “whole truth” is found in the collective wisdom of the past, not just the worldview of a single or select few authors:

The heretic (who is also the fanatic) is not a man who loves truth too much; no man can love truth too much. The heretic is a man who loves his truth more than truth itself. He prefers the half-truth that he has found to the whole truth which humanity has found. He does not like to see his own precious little paradox merely bound up with twenty truisms into the bundle of the wisdom of the world.

But contrary to popular belief, the people most willing to fall for half-truths aren’t those who don’t read. It’s those who do read, but who don’t read enough, that are most at risk. To illustrate this, Chesterton offers a brilliant example…

3) To Question “New” Ideas

Speaking as to why certain thinkers gain popularity for their seemingly “new” ideas, Chesterton writes:

…in all cases the same fundamental mistake is made. It is always supposed that the man in question has discovered a new idea. But, as a fact, what is new is not the idea, but only the isolation of the idea.

The idea itself can be found, in all probability, scattered frequently enough through all the great books of a more classic or impartial temper, from Homer and Virgil to Fielding and Dickens. You can find all the new ideas in the old books; only there you will find them balanced, kept in their place, and sometimes contradicted and overcome by other and better ideas.

To illustrate this point, he takes Nietzsche’s “revolutionary” idea of slave-morality, and shows why it really isn’t that revolutionary at all:

Nietzsche…held that ordinary altruistic morality had been the invention of a slave class to prevent the emergence of superior types to fight and rule them. Now, modern people, whether they agree with this or not, always talk of it as a new and unheard-of idea. It is calmly and persistently supposed that the great writers of the past, say Shakespeare for instance, did not hold this view, because they had never imagined it; because it had never come into their heads.

To prove why this is false, Chesterton points to a line from Shakespeare’s Richard III — a play written roughly 250 years before the birth of Nietzsche:

Conscience is but a word that cowards use,

Devised at first to keep the strong in awe.

-King Richard; Act V, Scene 3 of Richard III

It’s a line that sounds like it came from the mind of Nietzsche, yet it stems from the pen of Shakespeare. Chesterton ends his case as such:

Shakespeare had thought of Nietzsche and the Master Morality; but he weighed it at its proper value and put it in its proper place. Its proper place is the mouth of a half-insane hunchback on the eve of defeat.

Putting Ideas in Their Proper Place

Chesterton’s argument can be summed up as such: the reason why you read the classics is to put ideas in their proper place. This is because, as he says, “what we call the new ideas are generally broken fragments of the old ideas.”

Referring back to the example of Nietzsche and Shakespeare, Chesterton concludes with the following:

This case alone ought to destroy the absurd fancy that these modern philosophies are modern in the sense that the great men of the past did not think of them. They thought of them; only they did not think much of them. It was not that Shakespeare did not see the Nietzsche idea; he saw it, and he saw through it…

It was not that a particular notion did not enter Shakespeare’s head; it is that it found a good many other notions waiting to knock the nonsense out of it.

This, in Chesterton’s consideration, is why you read the classics: to find “a good many other notions” to “knock the nonsense” out of the fads, half-truths, and lies of the present…

How to Start?

The great books are best read together. We just started an online book club to study the classic texts of the Western canon, slowly, from Homer to Hemingway.

We will be reading one new book every month, split into two bi-weekly discussions: an introduction to the text, and then a deeper reflection on it.

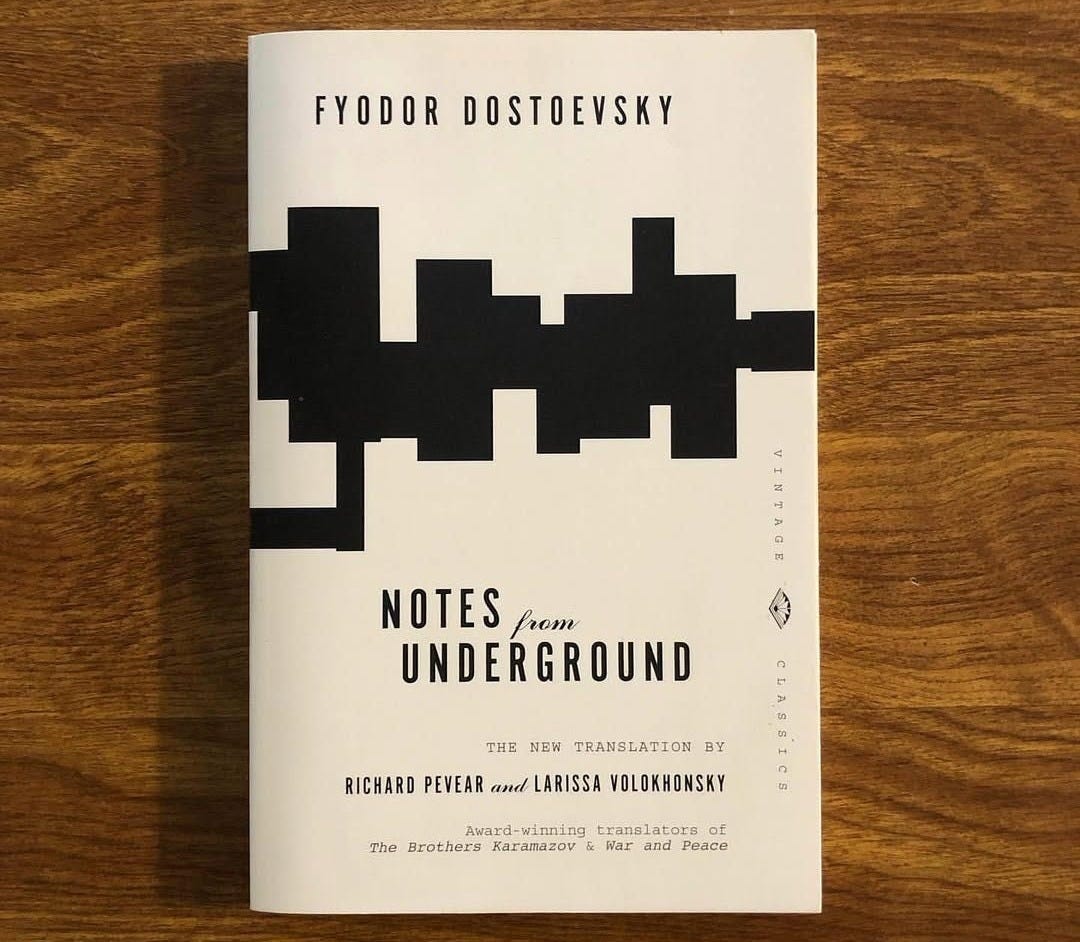

We’re about to start Dostoevsky’s “Notes from Underground” — the first meeting is on Wednesday, October 22, at noon ET!

All our paid subscribers can attend the live sessions on Substack, participate in the live chats, or watch the full recordings later if you can’t make it.

All inner circle / founding members (our 2nd membership tier) can join the discussion directly on Zoom — click the button below to join, and you’ll receive a Zoom link.

Everyone can read along at their own pace, but we will typically discuss the first half of the book (and major themes) during the first session, and the second half during the second session.

Note: general book club discussion is taking place in our subscriber chat room…

We read classics because they reveal how little human nature actually changes our desires, fears, and moral puzzles just wear new clothes. They train the mind to think with nuance and the heart to feel with depth. A classic isn’t just old; it’s a book that keeps outsmarting time, still speaking to questions we haven’t stopped asking.

I appreciate where you're coming from. But man, this stuff isn't light reading. Like I am doing the Aeneid because it was praised by Sean Berube. Man I have to sit down and power though it and it's still hard. They just burned down Troy and I've been on it like 2 weeks.lol.