Why “The Godfather” Is a Greek Tragedy

A far older story than you think...

Many modern stories you know well are in fact far older than you think. In the case of Mario Puzo's The Godfather, there's an underlying narrative that has been told by humans for thousands of years. That's because The Godfather is really an Ancient Greek tragedy.

In ancient Athens, the amphitheaters that played host to such tragedies were not merely there for entertainment, but as an essential pillar of ancient life. For the Greeks, the public performance of tragedy played a critical role in fostering the civic virtue of all audience members — indeed, attending the theater was essential to your formation as an individual, and part of your civic duty.

But when you think of wholesome, character-building movies, odds are you don’t think of ones about the Italian mafia. From drug dealing to mayhem and murder, these films depict the dark underworlds that exist far outside the realm of polite society.

Yet The Godfather stands out from the rest as a fundamentally moral story. Despite the violence they depict onscreen, the three films that constitute the trilogy offer a haunting meditation on power, fate, and the moral cost of ambition. Because even though they were filmed in the latter half of the 20th century, they tell a story as old as time.

The saga of Michael Corleone’s rise and fall in The Godfather is a Greek tragedy for the modern age, a cautionary tale designed to warn you about what happens when you compromise on your values and ignore what matters most in life.

Today, we explore it in depth to discover what it reveals about how — and how not — to live a life that’s truly meaningful…

Reminder: this is a teaser of our members-only deep dives.

To support our mission and get our premium content every week, upgrade for a few dollars per month. You’ll get:

Full-length, deep-dive articles every weekend

The entire archive of great literature, art, and philosophy breakdowns

Members-only podcasts and exclusive interviews

Part 1: Loss of Innocence & Rise to Power

The tragedy of The Godfather begins with a joy-filled celebration: Don Vito Corleone’s only daughter, Connie, is getting married. In attendance is her brother Michael, who, having eschewed the family business in favor of more wholesome pursuits, has since attended Ivy League university and become a decorated war hero.

Michael is considered a “noncombatant” even by enemies of the Corleone family, and is respected for his integrity in having rejected the life of crime. But when a rival family nearly kills his father, everything begins to change — and it’s where the first markings of Greek tragedy become readily apparent.

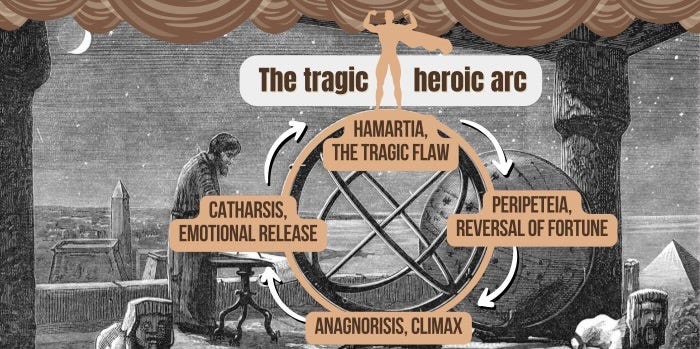

Aristotle defined tragedy as the fall of a great man through a combination of hamartia (tragic flaw), peripeteia (reversal of fortune), and anagnorisis (recognition or self-awareness). Michael’s hamartia is that he believes he can still preserve his integrity while stepping into a corrupt system, and this leads him to help his family in avenging their father.

As the film progresses, Michael leans into his new role with increasing success — but what sin loans freely in the present, it comes to collect with interest in the future. By the end of the film, Michael has seen his bride Apollonia murdered before his eyes, and has himself killed at least nine people, including his sister Connie’s husband.

Nevertheless, the first Godfather film still ends on a triumphant note, with Michael putting a conclusive end to the war between families and consolidating his power. But even here, all is not well. In a scene reminiscent of Genesis, Michael’s loss of innocence is highlighted in a conversation with his new wife, Kay. Whereas Michael used to share freely with Kay about his family — “That’s my family, Kay. It’s not me” — he now hides his dealings from her, demanding she never ask him about his business. Just as Adam and Eve become ashamed of their nakedness after they taste the forbidden fruit, so too does Michael now conceal his dealings from his loved ones.

But what’s worse is that a larger-scale tragedy is being set up, one which will only see its conclusion in the third and final “act” of the trilogy. It’s foreshadowed with the death of Don Vito, who finally passes away one day after playing with his grandson in the family garden. Upon his death, he has all a man could ever want — wealth and power, yes, but even more importantly a beautiful and loving family who truly care for him.

As we will see, it’s a reality that couldn’t be in any starker contrast to how Michael will end his days…

Part 2: Descent into Damnation

Widely regarded as one of the best sequels to ever be made, Godfather II uses parallel story-lines to recount both the origins and making of Don Vito, and the slow unraveling of his son.

Michael’s plot line begins with his decision to move the family out of New York, to Nevada. Desiring to put the legacy of violence and crime behind him, he aims to legitimize the family business by buying up casinos. But as he soon discovers, sin does not let you out of its grip so easily — much like the casinos Michael owns, evil makes it incredibly easy to sit down at the table and begin gambling. But when you want to cash out and leave, it’s a whole different story.

The irony is that in his quest to leave the world of crime behind him, Michael is forced to sin even further. Extortion, murder, and betrayal ensue as he undergoes the painful peripeteia (reversal of fortune) of Greek tragedy — yet in his case, the reversal takes place not in a single moment, but in the gradual unraveling of everything he holds dear.

Contrasting this breakdown, however, is the rise of Don Vito, now portrayed as a young man trying to make a name for himself in early 1900s New York. The film shows how he came to be “the Godfather”, and although certain aspects of his journey entail overt criminal activity, the overall portrayal of his rise is more sympathetic and wholesome. Specifically, you’re made aware that much of what he created was designed so that his children would never have to follow in his footsteps. It makes his lines to Michael in the first film even more poignant and heartbreaking: “I never wanted this for you.”

But where Vito sacrificed the integrity of his actions to serve his family, Michael sacrifices his family for the integrity of his actions. Because although he claims to do what he does to protect his loved ones, the actions he takes only serve to alienate and push them away. His relationship with his Kay erodes to the point at which she aborts their child solely to spite him, and the film ends with Michael doing the unthinkable — ordering the execution of his brother.

The irony is that, in executing his brother for “taking sides against the family”, Michael has done the exact same thing. But even here, the tragedy of The Godfather has yet to reach its painful nadir, as its main lesson isn’t revealed until the third film.

With elements of Greek, Shakespearean, and Biblical drama coming together in a poignant final act, The Godfather Part III reveals how men bring their life to ruin by losing sight of what matters most — and crucially, how you can avoid that very fate…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Culturist to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.