Why Tolkien Hated Disney

The role of danger in storytelling

In 1937, two landmark works of fantasy appeared within months of each other.

The first was The Hobbit, a children’s book written by an Oxford professor who had spent decades immersed in the legends and languages of Europe. The second was Walt Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, the world’s first full-length animated film and a commercial triumph that changed cinema forever.

J.R.R. Tolkien viewed the film with his friend C.S. Lewis, but he was far from impressed. In private letters, he called Disney’s studio “hopelessly corrupted,” and later insisted that Disney must never be allowed to adapt his own work.

Tolkien’s dismissal of Disney reflected a deep philosophical divide between the two creatives, one which still influences how stories are told today. In this article, we explore these two conflicting perspectives — and discover why it was that Tolkien hated Disney…

Tolkien’s Vision: Death, Defeat, and Resurrection

Tolkien spent his career immersed in ancient languages and early medieval texts. He particularly enjoyed myth and “fairy-stories”, both of which he believed preserved truths that modern society had largely forgotten.

To Tolkien, the value of these fairy-stories lay not in their ability to entertain you or transport you to magical worlds, but in how they reckoned with eternal topics such as evil, suffering, and the nature of heroism. Myths, as Tolkien understood them, were meant to help you confront the world. To engage with them primarily for their escapist value was to fundamentally mistake their purpose.

This belief played out in Tolkien’s own work, as he considered the writing of fantasy to be a kind of theological labor. His idea of “sub-creation” — the concept that man is made in the image of a creator God, and thus designed to create — clearly demonstrated this, but so too did his belief that well-made fantasy would point beyond itself and towards the divine.

In order to point that direction, however, you first have to reckon with the evil that lies in your path. In Tolkien’s work, this meant directly engaging with the harsh realities of life. In his children’s story The Hobbit, for example, he explores themes like death, fear, betrayal, greed, and war.

The Lord of the Rings goes even further, as the characters of Boromir, Frodo, Aragorn, and others become catalysts for a vast saga of moral testing, heroic suffering, and ultimate sacrifice.

But while The Lord of the Rings ends in triumph, that victory is only earned through the many struggles of its protagonists. The reason why this is becomes more clear once you consider Tolkien’s understanding of the nature of myth, and how it echoes the divine story:

“We have come from God, and inevitably the myths woven by us, though they contain error, will also reflect a splintered fragment of the true light, the eternal truth that is with God.”

-Tolkien, On Fairy-Stories

In light of this, you can begin to better understand how Tolkien’s work reflects the Christian story — resurrection and triumph are possible, but only in light of a prior death and defeat.

It also explains why Tolkien reacted so vehemently against Disney’s work, as he believed it lacked the requisite death that enabled resurrection…

Disney’s Vision: Safety without Struggle

Tolkien’s reaction to Snow White stemmed from this very concern. For while his own stories engaged darkness in order to achieve redemption, Tolkien believed that Disney had removed that darkness altogether.

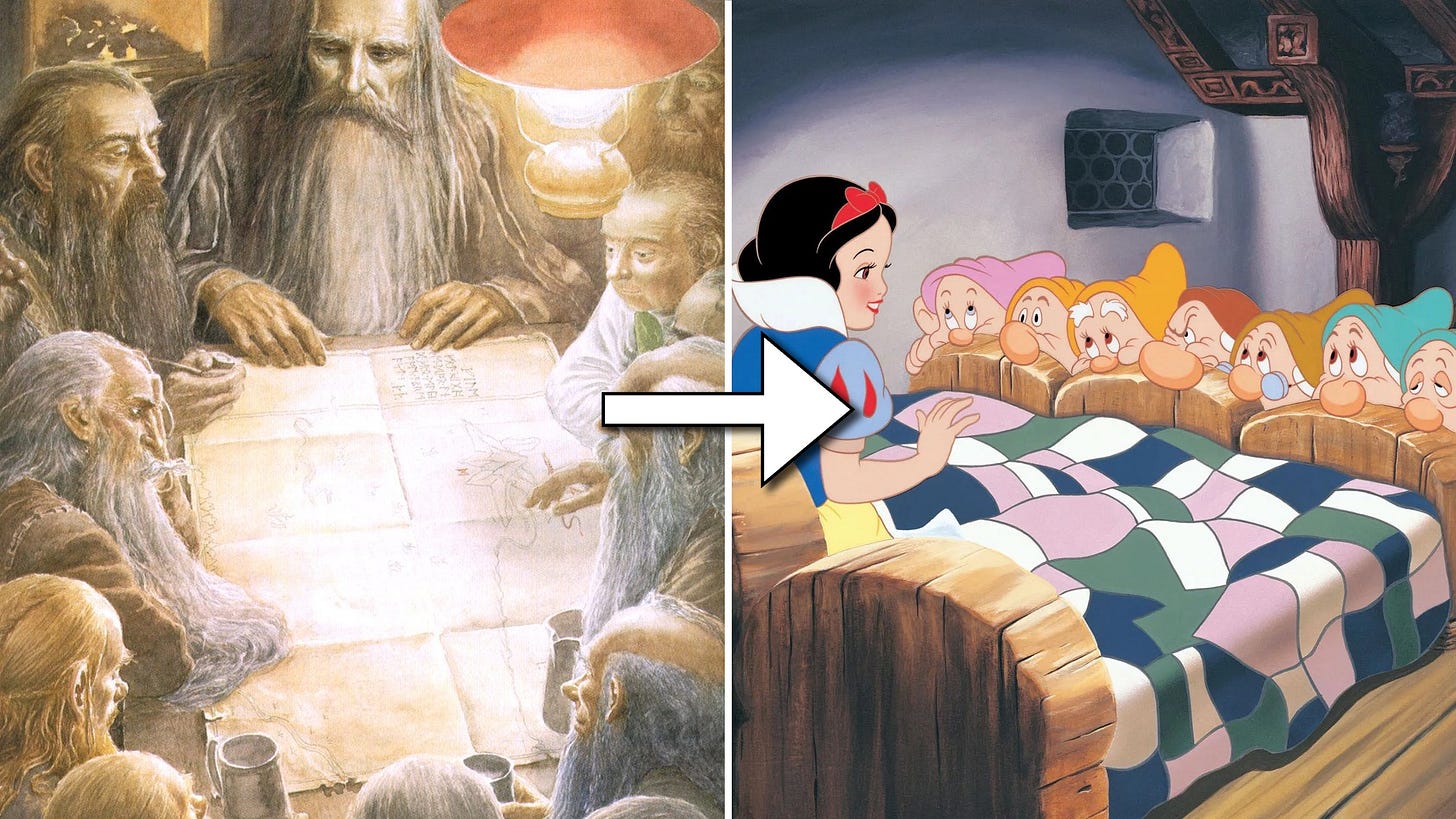

In the original 1812 Brothers Grimm version of the tale, Snow White is repeatedly hunted by her murderous stepmother. She bargains to earn her place in the dwarfs’ home, and when the evil queen is finally punished, she is forced to dance to death in red-hot iron shoes. In terms of tone and substance, the Grimm Brothers version is much closer to The Odyssey or Beowulf than it is to any modern children’s tale.

In Disney’s Snow White, however, the darker elements of the original tale are replaced with songbirds, sweetness, and a kiss. The dwarfs — figures with deep roots in Norse mythology and Germanic folklore — are no longer skilled craftsmen, but cheerful and comedic characters. Snow White is welcomed in without a struggle, and the evil queen disappears in a lightning strike. While the story itself remains entertaining, it lacks the depth required to engage earnestly with the evils of the world.

Tolkien believed that to strip this kind of story of its darker elements was to sever it from its purpose. Without the darkness there could be no light, and without genuine trial there could be no transformation. Fairy-stories, as Tolkien contended, were not supposed to merely entertain or comfort, but to prepare the soul.

What troubled Tolkien most, however, was not just the aesthetic change, but the deeper consequence: suffering had been made optional. There was no cost for redemption, and no consequence for evil. It all made for a fantasy with the edges dulled and the moral center hollowed.

Just why is incorporating real danger so important to storytelling? Well, Tolkien went on to develop his theory on the purpose of peril…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Culturist to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.