How to Write Well

Orwell's 6 rules for writing

Bad writing signals something deeper than poor style. It reflects vague thinking, evasiveness, and in many cases, a quiet form of dishonesty.

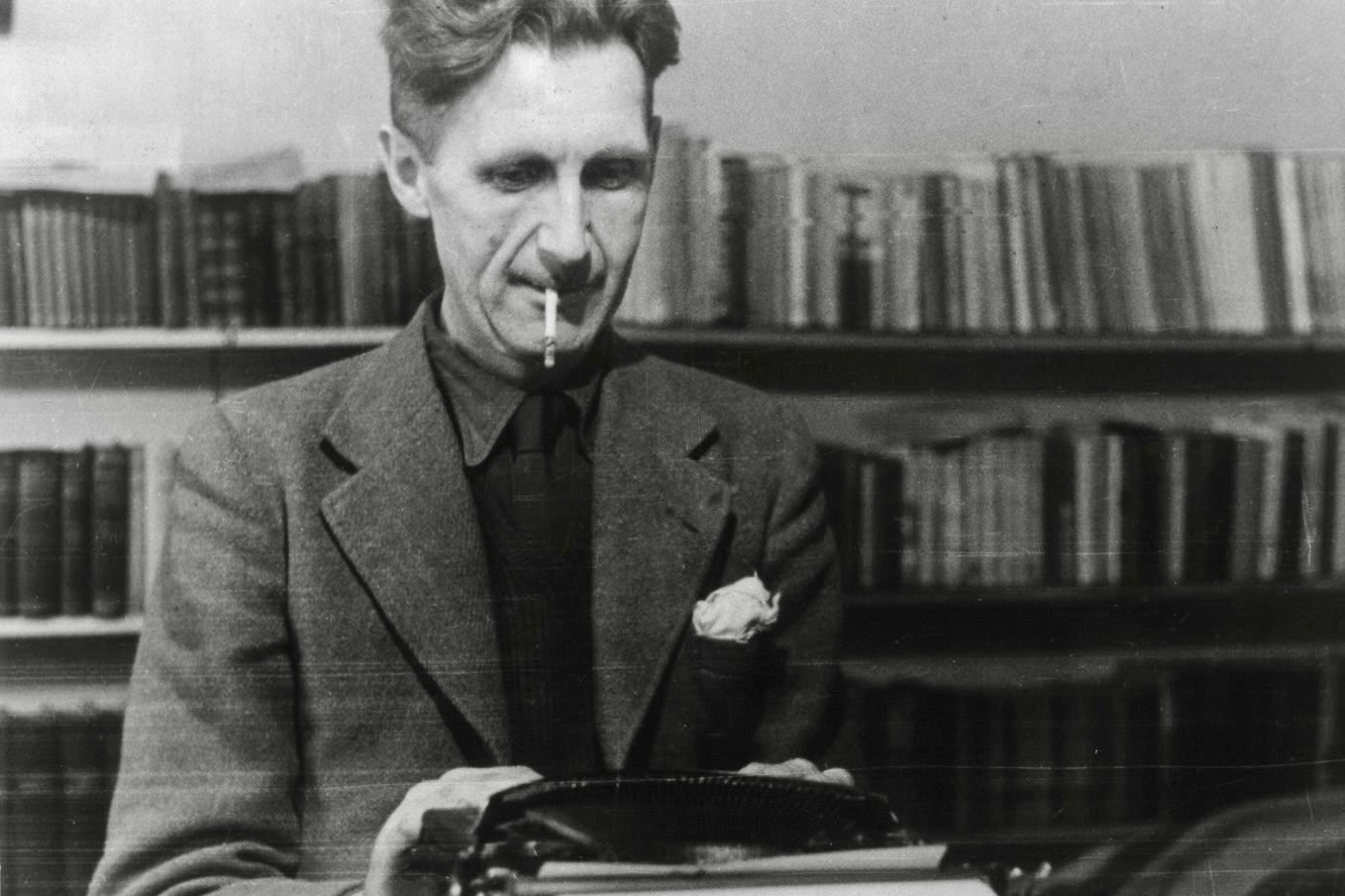

George Orwell saw this clearly. In his 1946 essay Politics and the English Language, he argued that language used in the media was frequently corrupted — and that this corruption served a purpose.

Official government reports, press statements, and political speeches were filled with vague phrases and lifeless prose not by accident, but by design. Words became tools for concealing action and dulling moral response: “We killed civilians” could easily be transformed into “collateral damage was incurred.”

To resist this rhetorical decay, Orwell laid out six rules for writing. They were aimed at political language, but they apply to nearly all forms of prose. Whether you're writing an email or an editorial, his advice remains one of the clearest guides to writing with honesty and precision.

Today, we examine each of Orwell’s six rules, and what they can teach you about thinking and writing clearly…

Reminder: you can support our mission and get tons of members-only content for a few dollars per month:

Full-length articles every Wednesday and Saturday

Members-only podcasts and exclusive interviews

The entire archive of great literature, art, and philosophy breakdowns

Rule 1

Never use a metaphor, simile, or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print.

At first glance, clichés seem helpful because they feel familiar. Who doesn’t want their writing to be immediately understood by the audience? Phrases like “Achilles’ heel”, “grasping at straws”, and “walking on eggshells” perfectly illustrate what you mean, and they are convenient to fall back on.

But therein convenience lies the problem — clichés replace original thought. They outsource the writer’s creative process to cheap terms that are, in Orwell’s words, “dying metaphors”. They are phrases that once evoked something vivid, but are now unremarkable.

“Bite the bullet” is a perfect example of a dying metaphor. While it originally referred to soldiers being forced to literally bite a bullet during surgeries in which no anesthesia was available, it’s now just shorthand for doing something unpleasant. The visceral nature of the original phrase has been completely lost.

This is why Orwell recommends against vague and forgettable stock phrases. Original images, even when simple, force the writer to think — and in turn, help the reader to see.

Rule 2

Never use a long word where a short one will do.

Big words may look impressive, but they often serve the writer’s ego more than the reader’s needs. Terms like “utilize,” “commence,” or “ameliorate” are usually chosen not because they’re clearer, but because they sound more important.

Orwell urges us to resist this impulse. The point of writing is not to show off your vocabulary, but to communicate your ideas in the most direct way possible. This doesn’t mean dumbing things down, however — it simply means removing barriers between your thought and the reader’s understanding.

Short, familiar words are easier to read and harder to misuse. They reduce the risk of confusion and make your writing more confident. Clarity, after all, is its own kind of elegance.

Rule 3

If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out.

Most writing suffers not from too few words, but from too many. Bad writers pile on extra clauses, repeat themselves, and pad their sentences with unnecessary phrasing that slows the reader down.

Orwell’s rule is a call for discipline. If a word isn’t doing useful work, delete it. The goal isn’t to strip language bare, but to tighten it so that every word pulls its weight.

Phrases like “in order to,” “due to the fact that,” or “at this point in time” can almost always be trimmed. Cutting them makes writing shorter, sharper, and far more persuasive.

Rule 4

Never use the passive where you can use the active.

Passive voice weakens writing by hiding the subject and softening the action. “The window was broken” tells you what happened, but not who did it. “He broke the window” is more direct — and more honest.

Orwell viewed this as more than just a stylistic issue. In political language especially, passive constructions are used to deflect responsibility. “Mistakes were made” is a classic example, as it admits something went wrong, but conveniently avoids naming the person responsible.

Using the active voice forces you to clarify agency. It helps the reader understand who is doing what, and how.

Rule 5

Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word, or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent.

Technical language, foreign phrases, and insider jargon often masquerade as sophistication. Writers who lean on these in their writing are often trying to signal intelligence or authority — but the real effect on the reader is alienation.

If your goal is to communicate clearly, you should always choose the word your audience understands without hesitation. Terms like “ameliorate,” “quid pro quo”, and “pièce de résistance” all have simpler, clearer substitutes. In Orwell’s view, writing in plain English is not a limitation, but a virtue.

Rule 6

Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.

Orwell’s final rule is a safeguard against blind obedience. These rules are meant to increase the quality of your writing, and if strict adherence to any one of them leads to confusion, awkwardness, or misrepresentation, then it’s better to break it.

There are moments when a cliché might work better than a strained original image, or when using the passive voice might be justified. But these should be exceptions, not habits.

Orwell’s deeper principle is that writing should always aim to make the truth more visible. If a rule gets in the way of that, discard it — honesty and precision matter more than any rhetorical convention.

This is good stuff! Hemingway immediately comes to mind here. He well understood the value of direct language and word economy.

This reminds me of a passage from Chesterton's Orthodoxy (had to look up which chapter, turns out it's Chapter VIII, the Romance of Orthodoxy) where he talks about long words as a sign of laziness in our modern busy world. "The long words are not the hard words, it is the short words that are hard. There is much more metaphysical subtlety in the word “damn” than in the word “degeneration.”"

Also, my grade 12 English teacher did an excellent job to pushing me to be direct. Probably lots of summarizing of passages of text and then editing them shorter is a good technique to practice writing more succinctly.