Why Christmas Is Not Pagan

The origins of December 25th

Every December, claims resurface that Christmas was originally a pagan holiday. December 25th, so it goes, was the date of a Roman festival to the sun god, and the Christmas tree originates from an ancient pagan ritual.

The confidence with which these claims are made often exceeds the evidence behind them. But when the historical record is actually examined, a different story emerges: not only did Christmas not take the place of pagan holidays, but pagan holidays tried to take the place of Christmas!

Today, we look at two of the most common arguments for why Christmas is pagan, and why the primary sources say differently. We also explore the reasoning behind why Christmas falls on December 25th…

Thank you so much for reading this year! If you’d like to support our work, please consider taking out a paid subscription — it helps us out enormously. Plus, you’ll get:

Full-length articles 2x per week

The entire archive of content (150+ articles, essays, and podcasts)

Membership to our biweekly book club (and community of readers)

We have just voted to read Beowulf, the foundational epic in the English language, in our book club. The first meeting is TODAY, December 17, noon ET — join us!

Roman Pagan Holidays

The most common claim about Christmas’s pagan roots takes us all the way back to Ancient Rome. The skeptics claim that December 25th had already belonged to pagan festivals like Sol Invictus and Saturnalia, and that early Christians simply tried to replace these holidays with their own version.

The sources, however, reveal quite the opposite.

Take Sol Invictus, for example, the festival of the “Unconquered Sun.” Although long practiced in Ancient Rome, its association with December 25th appears surprisingly late in the historical record. Depending on the year, Sol Invictus could be celebrated in August, October, or even early December. Eventually, it was indeed celebrated on December 25th — but not until the late fourth century.

By that point, Christians had already been identifying December 25th as the date of Christ’s birth for decades. St. John Chrysostom, in a sermon he delivered in 386 AD, describes Christmas falling on the 25th as a “long-standing tradition.” By the early fourth century, most Christian calendars shared that same date.

The closest Saturnalia was ever celebrated to Christmas was December 17th, so it too is ruled out as an alternate explanation. However, its shifting date reveals something interesting: that as Christian influence grew within the Roman Empire, pagan festivals changed their dates to move closer to the Christmas season.

The Roman Emperor in the middle of the fourth century, Julian the Apostate, might have had something to do with this. Lamenting the decline of Roman temple worship, he sought to restore the cult of the old gods. One way to do so was to move pagan holidays to take place on the same date as burgeoning Christian ones, so that people could celebrate on the days they were used to.

But as history reveals, the plan didn’t work, and Christianity emerged victorious over the pagan religion. December 25th, originally a Christian holiday, would forever remain as such…

Christmas Trees

For many people, Christmas without a Christmas tree doesn’t feel much like Christmas at all. But of course, Christmas had been celebrated for hundreds of years before the Christmas tree ever became popular. For this reason, critics claim that the Christmas tree was originally a pagan symbol, which Christians later co-opted for inclusion in their holiday.

While the historical record isn’t entirely clear on the origin of the Christmas tree, there are sufficient sources to suggest that it does indeed have Christian roots. Three of them are as follows:

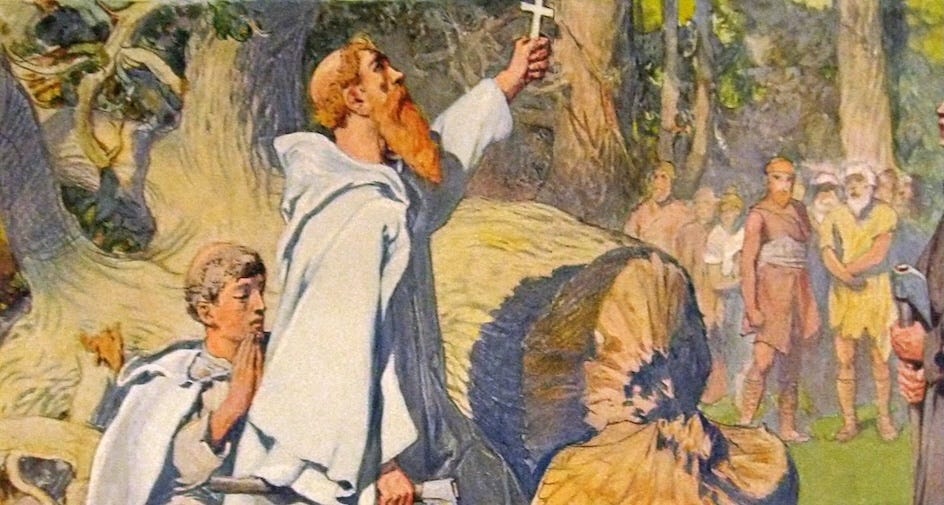

The first is the eighth-century missionary St. Boniface, who evangelized among Germanic peoples. According to tradition, Boniface cut down a sacred oak associated with Thor. When lightning did not strike him down (as he was told it would), Boniface pointed to a nearby fir tree and dedicated it to Christ, presenting it as a symbol of life and redemption. Regardless of whether or not every detail of the account is precise, the symbolism is unmistakably Christian, and explicitly opposed to pagan worship.

The second potential origin story appears in medieval Europe with the development of “Paradise Trees”. These were evergreen trees used in Christian mystery plays depicting the story of Genesis. Decorated with fruit to represent the Tree of Life, the Paradise Trees stood on stage during the performances that were traditionally held on Christmas Eve. Once the plays ended, the trees were left out, and inevitably got adapted as decorations for Christmas celebrations.

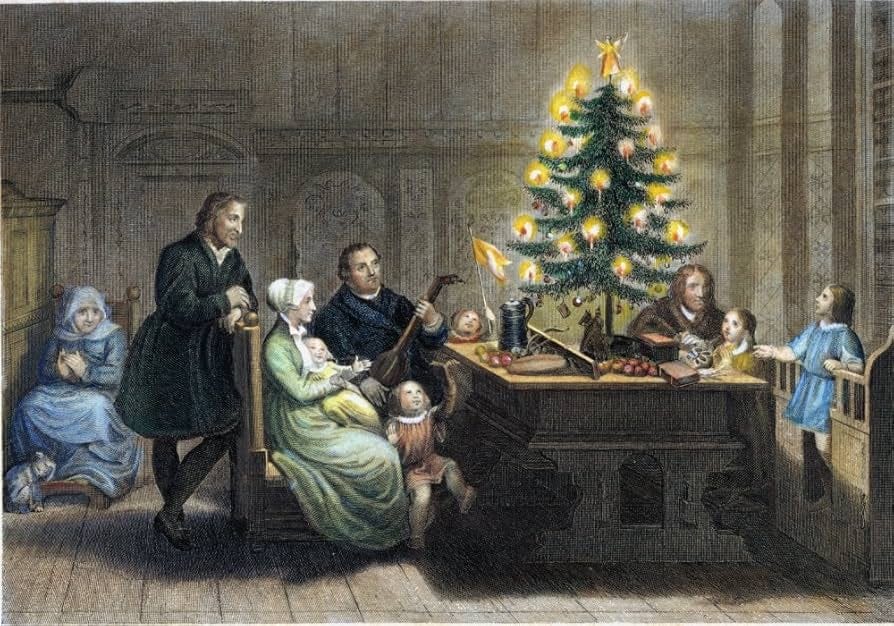

The third and final origin story comes from Reformation era Germany. According to an anecdote from none other than Martin Luther himself, the rebellious priest was walking through an evergreen forest on a winter night, when he was suddenly struck by the beauty of the stars shining through the branches. To recreate the scene, he placed candles on a tree inside his home. The tree was a reminder of the forest, yes, but to Luther it was also a visual reminder of creation, light, and the Incarnation.

Whatever you might think of these accounts, the most important thing is chronology. By the time Christmas trees became widespread in Europe (and later popularized in Britain through Prince Albert in the nineteenth century), pre-Christian pagan tree rituals had been extinct for centuries. Although there are similarities in the role of the trees in each, there is no direct line connecting pagan practice to the Christmas tradition, and no source which satisfactorily explains its evolution from pagan to Christian symbol.

Why December 25th?

Having explored the first two claims about Christmas’s supposedly pagan origins, the question that now remains is: why December 25th?

Among early Christians, tradition held that exceptionally holy figures died on the same calendar day they were conceived. Since their lives possessed a kind of providential symmetry, it followed that a “perfect” life began and ended on the same date.

Jesus, of course, was understood within this framework. While the Gospels don’t give a precise calendar date for the Crucifixion, they do place it during Passover, on a Friday, in the spring. Early Christians thus attempted to reconstruct the date using Jewish and Roman chronology, and by the third century two dates emerged in Christian tradition: March 25 and April 6. In the West, March 25 became the dominant reckoning.

Once March 25 was identified as the date of Christ’s death, it also came to be associated with the Annunciation, the moment of Mary’s fiat and Jesus’s conception. From there, the logic followed naturally, with nine months after March 25 placing the date of Jesus’s birth on December 25.

The date for Christmas, then, wasn’t fixed by borrowing from a pagan festival, but by looking to a chain of theological reasoning that moved from the Passion to the Annunciation and finally to the Nativity.

Whatever you believe about the accuracy of March 25th as the date of the Crucifixion, at least one thing is clear: December 25th as the date for Christmas wasn’t chosen for pagan reasons, but overtly Christian ones.

Christmas is a Christian holiday as its meaning, but it basically incorporates older winter traditions from Roman, European, and even Central Asian cultures. I found this reading unmistakably Eurocentric to be honest. Many symbols (trees, lights, feasting, gift-giving) come from ancient pre-Christian winter rituals. Just the meaning got fit in the same 'season' with Christ's birth.

True True. But I always thought that with the ancient roots into the solstice and the festivals and practices already around the world that that the argument is it was shifted away from the 21st to the 25th. An assimilation of thousands of years of evident stone records that this was a time of festival and marking of the stellar moment. Of the turn back to the light.

“Oh! What are you doing in this time of the year? You don’t need to stop doing that. Why don’t you join up your party with what we do too”?

And then over the centuries the dominant 25th becomes the norm. It is fascinating that even after 2000 years we have these folk memories and deeply carved evidence point points for something thousands of years older than the Nativity.

It was my understanding that early Christian festivals were linked to as you say the deaths of Saints and key people. Seems an incredible coincidence that 300 years after the fact Emperor’s and bishops decided that it coincided with all those other big festivals of the world!

A wonderful world of Folklore and story!

Time is inexorable.