What Makes a Genius?

William Blake's case for the spiritual

What makes a genius?

How do some artists develop a style that is, at once, utterly distinctive and yet, also, universal? And what is the meaning of that seemingly paradoxical link?

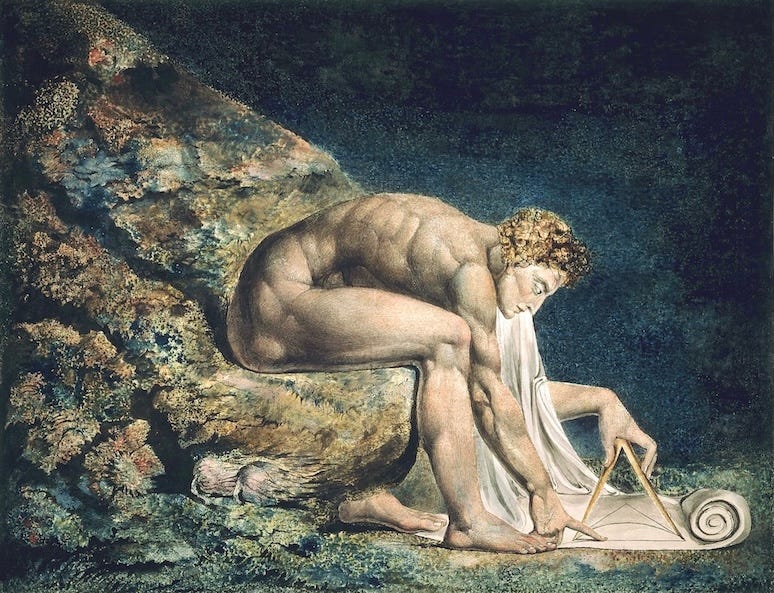

William Blake provides a case in point. Nowadays, he is as famous as Shakespeare and Milton, Turner and Constable, amongst English poets and painters. Born in 1757 and living until 1827 (the bicentennial of his death is in a couple of years), his influence reaches from the Pre-Raphaelites to American transcendentalism, from the beat poets to comic books.

A massive retrospective of his work in 2019 at Tate Britain in London was a blockbuster: a quarter of a million people wanted a direct encounter with his engravings, watercolours and illuminated books.

And yet, commercial success eluded him across the three score years and ten of his mortal life. He wanted to be well-known, shaping the zeitgeist. But, as he observed in a letter to one of his most loyal patrons, William Hayley:

Money flies from me. Profit never ventures upon my Threshold, tho’ every other man’s doorstone is worn down into the very Earth by the footsteps of the fiends of commerce.

I think that reference to “fiends” provides a clue. Blake was not allergic to selling his work, as if he believed that the mark of genius is to fade in an impoverished garret. Quite the opposite: he thought that his work should command high prices; he believed in being paid.

However, his own tutelary spirits had a tight hold on him. They would not suffer compromise, and he so didn’t: “I was commanded by my spiritual friends,” he explained to a friend. The upshot was that his output was treated warily, with he himself regularly being held mad. In the long term, adherence to his vision paid off.

But does that faithfulness, and its origins, cast any light on the nature of genius?

Reminder: you can support our mission and get tons of members-only content for just a few dollars per month:

Full-length articles every Wednesday and Saturday

The entire archive of great literature, art, and philosophy breakdowns

Members-only podcasts and exclusive interviews

In the last year, we’ve written about everything from the nature of evil in Milton’s Paradise Lost, to J.R.R Tolkien’s sacred art of sub-creation, to C.S. Lewis’ case for why myths matter…

The word itself offers a clue. “Genius” comes directly from the Latin for guardian spirit, genius, also carrying connotations of creative power — hence the etymological link to “generate”. Blake’s loyalty stemmed from a realisation that inspiration is precisely that: to be inspired, or breathed into, by a spirit. He was in touch with a source with which he had to collaborate and, conversely, from which to be uncoupled would be creatively fatal.

Genius nowadays doesn’t imply spoken to by a god; the word had been shifting meaning in the decades before Blake’s birth to the sense it has now: an exceptional natural ability — with the stress on “natural”. But the evolution of the word illuminates a second element to Blake’s genius. For alongside guarding his muses, resisting naturalism drove him, too.

He expresses this opposition throughout his work, a good example being found in an early pamphlet, There is No Natural Religion, printed in 1788. In it, he explains how he differs from some of the key thinkers of his age, several of whom he knew personally.

One was the revolutionary write, Thomas Paine — whose own pamphlets were an enormous success: The Rights of Man in 1791 sold 50,000 copies in the first weeks. Alongside Paine, Blake knew the early feminist, Mary Wollstonecraft, and the philosopher of anarchism, William Godwin. He also read contemporaries such as the economist, Adam Smith, and the founder of utilitarianism, Jeremy Bentham. One of the beliefs that these figures held in common was a conviction that newly emerging scientific explanations for things were eclipsing older, supernatural ones.

Blake thought that just cannot be right.

One reason, summarised in There is No Natural Religion, connects with his genius and its spiritual not natural source. Blake pointed out that if human beings were the generators of their own inspiration, borrowing too from the natural world around them, then creativity would soon grind to a halt. If all we had to go on were five senses and our reason, then art would soon degenerate into little more than variations on long-established themes.

The argument is relevant now. Take the generation of imagery and words from AIs. My bet is that we will soon become bored by these computer outputs, though initially they appear impressive, because they lack true inspiration. They will, in time, show themselves to be the clever substitutions that they are: extrapolations from work with which we are already familiar.

Blake knew that work of genius is different. It arises from the fact that human beings have access to more than what their eyes, ears and minds tell them. “Man’s perceptions are not bound by organs of perception,” he wrote. “He perceives more than sense can discover.”

That word “man” unpacks that “more” because Blake meant man not only in the sense of human being, but also in the sense of creatures who have intelligence or “mentality” — “men” and “mentality” sharing the same root. Intelligence, for Blake, does not therefore mean cleverness but the capacity to resonate with the divine wisdom that makes all things: the aboriginal creator. This link is made in a poem that begins:

‘Now Art has lost its mental Charms

France shall subdue the World in Arms.’

So spoke an Angel at my birth,

Then said Descend thou upon Earth:

Renew the Arts on Britains Shore.

Genius is for Blake not a private possession or a natural one, but a sharing in godly creativity that gives rise to what we call the natural world. The vocation of the artist is, therefore, to work with this otherworldly energy, known in the vitality called life. “Energy is the only life,” Blake wrote. And that links to a final part of Blake’s understanding of his genius: in a word, the role of imagination.

“A fool sees not the same tree that a wise man sees,” he explained, because whilst the fool sees a tree naturally, “only as a Green thing that stands in the way”, the divine imagination moves the artist “to tears of joy”.

This happens not because imagination adds something to the tree, but because the imagination of the artist sees the tree — and reality — as it truly is. “To the Eyes of the Man of Imagination, Nature is Imagination itself,” Blake continues — and that means nature is a manifestation of the divine. “If the doors of perception were cleansed, everything would appear to man as it is: infinite,” was his famous summary.

Genius arises, therefore, from a connection with the more than human that makes us human.

Very well written and thought-provoking. Thanks!

Thanks for bringing us back to the sacred nature of genius.